Rural Molise: The century-long exodus continues but three quaint villages retain their historic charm

(This is the second of a two-part blog on Molise, Italy’s least-visited region.)

CAMPOBASSO, Italy – People in Molise are kind of the happy, slapstick folks of Italy. They don’t take themselves too seriously. When you’re the second-smallest region in Italy and you have four times fewer visitors than the next most-ignored region, you develop humility.

A good sense of humor also helps.

The region’s motto? “Molise doesn’t exist.” Want a “Molisn’t” T-shirt? It makes a great souvenir. Bring it home with your giant ball of caciocavallo cheese.

Molise is Italy’s punchline. But I won’t compare it with punchlines in the U.S. It has less crime than Detroit. In fact, when I went to Molise for my birthday two weeks ago, I don’t recall seeing a police or a Carabinieri station. It’s prettier than my favorite punchline: Nebraska. Molise is 55 percent mountains.

However, unlike Detroit, which is making a comeback, Molise is dying. Its population has dropped from 406,823 in 1951 to 305,617 in 2019, a freefall of 25 percent.

In fact, in 2019 Molise’s government started offering 700 euros a month to anyone who would move into an underdeveloped area.

Driving around rural Molise on our last day, Marina and I saw beautiful rolling hills, patchwork farmland and hilltop villages. We saw the Turturri, the ancient migration trails that crisscross the landscape. We saw peaceful piazzas with magnificent vistas.

But we didn’t see many people. Piazzas were nearly empty. Cars were few and far between. Village train stations were locked up like they were historical landmarks. Since World War II people have fled Molise as if locusts invaded instead of tourists.

The reasons are many. World War II left Molise heavily damaged from bombs and Italy’s fascist policies. They saw no social advancement from working the mountainous landscape. They’re still moving out today.

As “Almanac: Molise Itineraries” published in 1972: “To the contrary, the people reply ‘No!’ to the spiritual rurality of the Molise region: they do not accept it as their specific vocation and by emigrating hope to free themselves from the degrading condition of peasant and ‘bondsmen,’ since they actually feel like servants in the context of today’s society.”

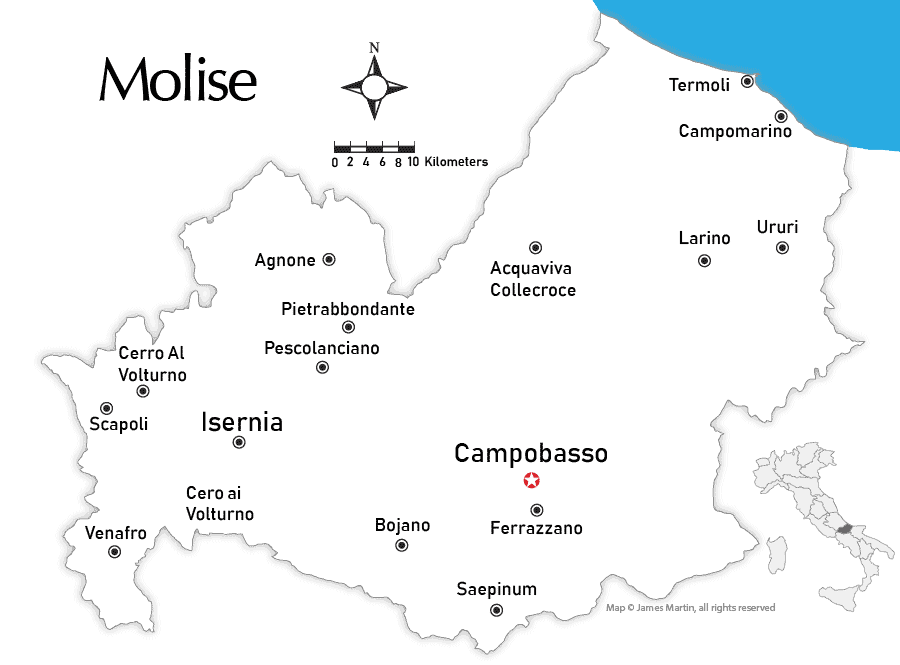

Actually, Molise does exist. It exists beyond Campobasso, its charming little capital. We visited three villages that symbolize what Molise is all about: Ferrazzano, the ancestral home of American actor Robert De Niro; Pietrabondante, home to an ancient Samnite theater complex; and Agnone, boasting the world’s oldest bell foundry and supplier of all bells to the Vatican.

Ferrazzano (pop. 3,300)

It’s only three miles south of Campobasso but it’s no suburb. Italian suburbs are different than in the U.S. Italian suburbs don’t have McDonald’s, cul-de-sacs and divorcee bars. Ferrazzano sits atop a cliff at 870 meters (2,854 feet) hovering over Campobasso and the countryside beyond.

We drove the windy road up from our hotel in Campobasso’s old town and parked in a small parking lot. The panoramic view, even on a gray, drizzly, 48-degree morning, stretched forever. Clay tile roofs folded into the rolling foothills of the Apennine mountains, with morning fog hovering over a forest of pine trees.

An old man was the only person around and I played dumb tourist by asking a question I was afraid he’d heard thousands of times.

“Ever seen Robert De Niro here?” I asked.

Thankfully, he didn’t roll his eyes. He actually said De Niro has given a lot of money to the town and that he may have appeared.

It’s a legend,” he said. “Some say yes; some say no.”

In truth, De Niro is not from Ferrazzano. His great grandparents are. In 1887 Giovanni Di Niro and Angelina Mercurio emigrated to New York where De Niro was born in 1943. Notice they tweaked the surname. They had no specific reason. At the time it was almost an unwritten rule that all immigrants to the U.S. changed their name.

Also, De Niro did visit. At least, he did according to Maria Assunta Baranello, head of The Fan, a Ferrazzano organization which has dedicated a film review to him for years. However, the visit was back in the late ‘60s, about the last time De Niro could walk anywhere, let alone his ancestral home, and not get recognized.

Baranello wrote in her newsletter: “The old men of Ferrazzano, who deserve a special mention, a ‘red carpet,’ a ‘career award’ for their wisdom and composure, told us about this dazed, extroverted and emaciated young man who, at the end of the ‘60s unexpectedly showed up in town eager to visit the places of his ancestors and to demonstrate in his own way (even performing as an unlikely singer in the square) his personal bond with Ferrazzano.”

In 2006, De Niro received Italian citizenship and a passport from Rome mayor Walter Veltroni. He threatened to use it during his verbal wars with Pres. Donald Trump. In 2016, shortly after Trump was elected, De Niro, looking exasperated, told talk show host Jimmy Kimmel that he’s from Ferrazzano, “And I may have to move there.”

It doesn’t take long to walk around Ferrazzano. We walked along narrow cobblestone paths between stone homes to protect from the biting winter cold. The town gets a couple inches of snow per year and winter weather is often in the 30s.

The narrow paths lead to a central square anchored by a bizarre building. Teatro Del Loto looks like a Mexican motel with two stories and beautiful turquoise patterns on the ground floor. Built in 2007, it’s been called “The most beautiful little theater in Italy.” Posters advertised upcoming performances such as “Il Boschetto,” “Robin Hood” and “Il Grande Inquisitore.”

Climbing farther, we came across Ferrazzano’s castle, small like the town and dating back to the 15th century where it was reconstructed over the ruins of a structure dating back to the 11th century.

We found nothing open in Ferrazzano, and we were hungry. If you think country cooking is the best, try country cooking in the least touristy region in Italy.

Pietrabbondante (pop. 740)

This is about as close Molise gets to a tourist town. Located 30 kilometers (19 miles) northwest of Campobasso, Pietrabbondante attracted us for the ruins of a theater complex that was built at the same time as the Roman Colosseum.

As the weather grew cold, windy and drizzly, we climbed up the road to 966 meters (3,169 feet) to the theater complex gate at the outskirts of town.

Locked.

It’s usually open to the public until 4:45 p.m. daily and apparently well worth it. Marina visited in 2010 when she took the top photo. The complex was built by the Samnites, an ancient, agricultural-based people who inhabited this region before the Romans swallowed them into their empire.

From the 2nd century B.C. to 95 A.D., the Samnites built a theater that seated 2,500 people and is still used for a summer theater festival. It sits on an Ionic portico that Hannibal destroyed in the 3rd century B.C. on his march toward Rome. It’s adjacent to a temple that stood 22 x 35 meters (72 x 115 feet) of which eight columns that fronted the temple remain.

It’s a remarkable complex and I imagine it would be a spectacular evening to sit on 2,000-year-old stone steps and watch a play while beating Rome’s summer heat. Even shivering in the cold on a quiet March day, we marked it on our to-do list.

The Samnites are still sacred around Molise. In the middle of Pietrabbondante stands a giant statue of a Samnite warrior, with shield and towering headdress, built in 1920 on money raised in the U.S., as a memorial to the Pietrabbondanti who died during World War I.

Hovering above the town square is the trademark giant rocks where the town begat its name which means “Stones in abundance.”

The first building we came across in Pietrabbondante was La Taverna Dei Sanniti. It’s a sprawling, elegant restaurant that serves some of Molise’s highly underrated cuisine. Dino Di Iorio, the dapper and enthusiastic owner, started us with fried caciocavallo, Molise’s signature cheese you see hanging like giant cheesy Christmas balls from ceilings around the region.

They fry it on both sides and it comes across as this biting, tangy snack that made us order a second serving. Then came the tacconelli, triangle-shaped pasta with meat sauce and then Centerba, Molise’s strong herbal liqueur.

Topped with local red wine, another one of Molise’s hidden gifts to mankind, it was the kind of meal you won’t find in tour guides or in any Italian restaurant in the U.S. It was a meal fit for Robert De Niro.

Agnone (pop. 5,105)

It’s only 12 miles (20 kilometers) north of Pietrabbondante but the windy, mountainous road took us nearly an hour to reach it. Agnone is a prime example of the traveler’s motto: It’s not just the destination, it’s the journey.

The country road runs parallel to the town, which hovers across a valley on a mountain cliff like a floating city. The town was once one of the most notorious in Italy. It experienced a massive exodus after Italian unification in 1864 when locals fled to escape excessive taxes and interest rates at upward to 20 percent. The desperate townsfolk were stealing crops and in 1863 the town prosecuted 624 cases of illegal felling of trees.

During World War II, Benito Mussolini used Agnone to exile political opponents and built a concentration camp for gypsies.

Today, people go to Agnone to see bells.

The Campane Marinelli bell foundry has been run by the Marinelli family for 1,000 years, making it the oldest bell factory in the world and the oldest family run business in Italy.

Agnone’s streets were empty as we pulled into town, the cold keeping locals in and the summer tourist season still far away. The foundry is a five-minute walk from the town center. Only two other people joined me on a factory tour.

He showed us a 1,000-year-old bell and one that stood 7 meters x 7 meters and weighed 200 tons. The museum has dozens of photographs showing bells at commemoration and being placed in the Vatican. There’s a bell commemorating the 150-year anniversary of Italy’s unification.

We then went into the foundry where they’ve used the same methods to make bells since the beginning. In fact, Molise’s metal-working tradition dates back 2,200 years when they made bronze statues to decorate Samnite temples.

The foundry is dark, foreboding. Bells hang from chains. Fires blaze where they forge the iron. Firewood is piled high near the ceiling. The guide took a gong and banged out “Jingle Bells” on one of the bells. (Get it?)

On our way out of town back to Campobasso, we saw our GPS kept going in and out. So did the radio stations. Welcome to rural Molise, the back of Italy’s beyond.

If you would like to go …

How to get there: About a dozen trains a day leave from Roma’s Termini station to Campobasso. The 3 ½-hour trip, with a change at Rocco Ravindola, starts at 16.05 euros. It’s better to rent a car. The journey without stops is 2 hours, 45 minutes.

Buses leave Campobasso’s bus terminal near Via San Giovanni every four hours for Ferrazzano. The 13-minute ride is 1 euro. A taxi takes eight minutes and costs 12-15 euros.

One bus daily leaves Campobasso for Agnone. The 2 hour, 35-minute ride costs 3-9 euros. One bus daily continues from Agnone to Pietrabbondante. Thirty-minute ride is 1-2 euros.

Where to stay: Palazzo Cannavina, Via V. Cannavina 24, 39-393-482-0000, Hotel B&B Campobasso – Palazzo Cannavina, info@palazzocannavina.com. Six beautifully decorated suites in the old town. I paid 120 euros a night for the Suite Cannavina.

Where to eat: La Taverna dei Sanniti, Località Sant’Andrea, Pietrabbondante, 39-08-65-769-007, Home (tavernadeisanniti.it), tavernasanniti@tiscali.it, 12:30-3:30 p.m., 7:30-11:30 p.m. Tuesday-Sunday. Traditional Molisano dishes and pastas such as roast lamb and tortellacci in an elegant atmosphere at cheap prices.

When to go: At 700 meters (2,300 feet), Campobasso is cool all year round. July and August have lows of 64 to high of 80. January is coldest at 35-44. Our visit in late March had temps between low 40s and mid-50s. Molise gets little rain and few tourists year round. It does get snow in winter.

For more information: Infopoint Turistico Molise, Piazzetta Palombo, 39-389-953-3644.

April 12, 2022 @ 3:53 pm

Grazie for a very detailed blog. Interesting history on bells and the oldest bell foundry. De Niro may still want to escape back to his ancestral lands. And you’re right, De Niro was very outspoken about Trump… describing him as if he was running the White House like a mob boss but not nearly as smart.

June 17, 2022 @ 5:49 pm

I agree De Niro may want to escape back to his homeland. I like him as an actor, but we don’t need his political views shoved down our throats. He is from the same region as my late father , who would not like his views either.

April 12, 2022 @ 9:08 pm

Excellent article. I knew nothing about the history of Molise. Great photographs.

Another beautiful area of Italy to discover.

April 13, 2022 @ 6:58 pm

Molise is the only region of Italy I have not visited. It looks interesting, but since I don’t like travelling in Italy in summer I am unlikely to find anything much open…a bit like parts of Puglia.

April 18, 2022 @ 6:06 am

In a nice bit of serendipity, CBS’s Sunday Morning show this morning had a segment by correspondent Seth Doane (who lives in Rome) on the Marinelli bell foundry.

https://www.cbsnews.com/video/forging-traditions-italian-bell-makers/#x

February 9, 2023 @ 4:43 pm

Check out the village near by Ferrazzano named Toro! Would like to hear about this village

April 14, 2023 @ 8:41 am

I will check out Toro next time I’m in Molise. (Sorry this is late. I just saw it this morning.)

February 9, 2023 @ 4:48 pm

Would like to hear about a village called Toro . Near Campobasso and Ferazzano !

April 23, 2023 @ 12:45 pm

Sure. Tell me.