Skocjan Caves a must do in Slovenia, the cave capital of Europe

DIVACA, Slovenia — Have you ever wondered what’s under your feet? I’m not talking about under the grass or concrete or sand. I’m talking about under your feet boring deep into the earth. This planet is 8,000 miles from where you are through the middle of the earth to the other side. That’s a lot of molten rock, continental crust and, well, sand. But you don’t have to go to the center of the earth as Jules Verne’s novel did to get startled by the unknown.

In Slovenia, you can become slack jawed by going under the earth only 100 yards.

This spectacular country on the north end of what was Yugoslavia is known for its great wines, roasted meats and affordable skiing. But underneath it all lie cave networks that are among the most vast in the world. Slovenia has 11,500 caves. About 250 new ones are discovered every year.

“We are very curious people,” one caver said.

I toured the Skocjan Caves on the far west end of Slovenia. It’s about five miles from the border of the Italian tail that slips down the east side of the Adriatic Sea. This area of Slovenia is marked by rolling green hills and cute little villages with not a single reminder of the communist past from 25 years ago. Skocjan Caves stretch 6 kilometers. We were going to walk 2 ½ of them.

About 50 of us gathered outside the cave entrance with our English-speaking guide from the Skocjan Caves Regional Park (www.park-skocjanske-jame.si, psj.info@psj.gov.si, cost: 16 euros). Caving is THE thing to do in Slovenia. Not to say it’s popular but our guide had to wait until other briefings were given in Slovene, German and French. I believe some guide also speaks Hmong. I’m not sure.

“Caving” isn’t the right term. In reality, caving is exploring, putting a flashlight atop your helmet and crawling through tiny openings in the earth, hoping a flash storm doesn’t hit from above. I’m a little claustrophobic but even a vampire who sleeps in a casket wouldn’t want to drown like a rat in a flooded corner of a cave. What we were walking through were openings 30 meters high. You could fit a 10-story building. The caves’ northwest section is reserved for experienced cavers, like our guide who has apparently spent more time underground than Al Capone.

The caves themselves seem as old as earth itself. They’re estimated to be 2-3 million years old. Yet these weren’t discovered until 1851. To reach them we walked down a relatively modern 100-meter-long tunnel, built in 1933. We entered a vast cavern with a long walkway. The caves are lit from below so they appear a bit like a giant haunted house. We could not take photos. Safety reasons, they said. They didn’t want people not watching where they were walking. I looked down at about 50-foot drop. Forgot myself. A stumbling Japanese tourist with a video camera could knock my camera right into a gaping maw of darkness.

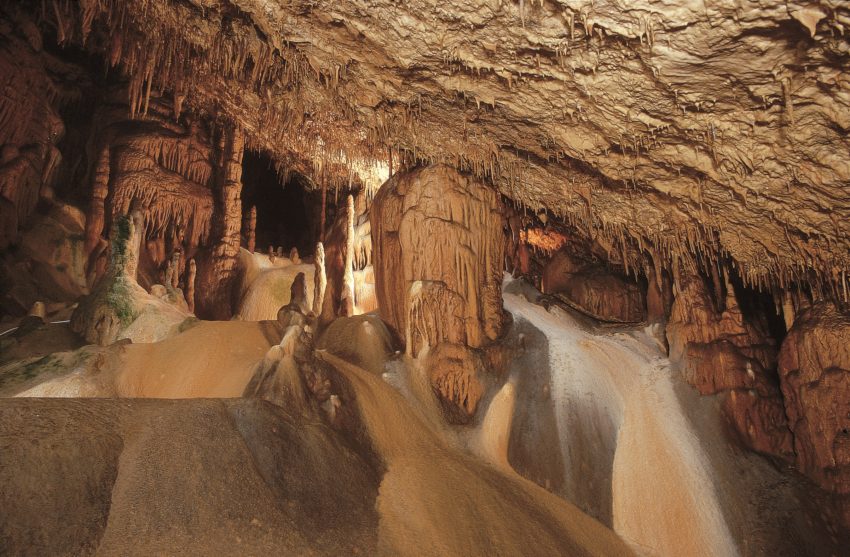

As we walked farther inside, the stalactites (hanging from the ceiling) and stalagmites (sticking out of the ground) were getting bigger. Most of these were formed 100,000-300,000 years ago and were topping 15 meters long. Much of the caves’ formation is based on the moisture above ground. These caves were the first underground wetland discovered in Europe and some of the stalactites drip like sweaty arms. Rain seeping down have also formed a very interesting pool formation. About 50 pools are piled up on top of each other like giant soup bowls. The guide pointed out small rock formations that look just like little dogs guarding their water supply.

These caves have been explored since 1933, when the most crude form of exploration aide was built. Narrow steps have been carved out of the cave and lead all along the wall. One misstep and you’ll go tumbling into oblivion. A simple rope serves as a weak guardrail. But it also blocks all entrances. Walking along these early 20th century stairwells is strictly prohibitive as if one glance wasn’t enough warning. But from a distance, the crude, jagged stairs look like old Roman steps I’ve seen near 2nd century B.C. ruins. They give the cave an even more prehistoric look.

We soon came into a cavern the size of an opera house. It’s called, appropriately, the Great Chamber. It is 30 meters high and 120 meters long. You could almost fit an indoor football stadium inside it. It is filled with life that you can not see — thankfully — such as bats, spiders and beetles. Here is where the cave gets noisy. A river runs through it. In fact, early explorers traced it 50 kilometers outside the cave to under a snowy mountain on the Croatian border. Flooding, however, is an issue. Last year, heavy rains caused the river to swell to within 15 meters of the long narrow bridge we crossed. These caves are no places for surprises. Guides carefully monitor weather reports. If heavy rains continue for days, they close the caves.

We finally surfaced through a giant, gaping opening in the cave and took a cable car all the way back to the top where a cold beer and our cars awaited. So did sunlight. Slovenia: a country as fascinating underground as it is above.

October 19, 2020 @ 7:42 pm

Would love to visit the caves