Tajikistan: USSR’s poorest ex-republic stands tall with pretty peaks and a sparkling capital

(Third of a four-part series on my three-week trip through Central Asia.)

ARTUCH, Tajikistan — The Artuch Mountaineering Camp sits in a deep bowl in the middle of postcard-perfect snow-capped mountains and a forest of juniper trees. A small river babbles down the valley into a little village below. I’d feel as if I was in Switzerland except for the camp’s origins.

USSR, 1971.

Back when the Cold War had the world on edge, climbers from everywhere behind the Iron Curtain rushed here to exercise one of the few freedoms they had. Climbing was their way of seeing the world. However limited their freedom was on the ground, altitude has no wall.

And the views aren’t bad.

The camp hasn’t changed much since it was built 48 years ago. I believe the bathroom in my roomy cottage was modernized. But my prayer room with the huge carpet still existed and the expansive dining/TV/bar room with adjacent lodging quarters was around.

The mountains certainly haven’t changed. They all look painted by a romantic artist who didn’t think it implausible for each mountain to have its own corresponding lake below it. The snow, even in late May, stretched deep below the peaks and the lakes were so clean and clear I could fill my water bottle without worry of some third world illness I can’t pronounce.

Here’s another fact that hasn’t changed: Tajikistan, the poorest state in the USSR, is still the poorest former Soviet republic. During the days of the Soviet Union, Tajikistan represented only 0.2 percent of the country’s gross domestic product. After independence in 1992 and a civil war that cost 60,000 lives, its GDP dropped 70 percent. It did rebound, growing about 10 percent a year from 2000-07 but its average per capita income is still only $2,100 a year, lowest of the former 15 Soviet republics.

Emomali “Rahmon” Rakhmonov, a former regional communist boss, took over as president in 1992 and has been in charge ever since. Tajikistan has one political party, the People’s Democratic Party. He’s it.

Yet despite the lingering communist hangover, the bloodshed and the poverty, Tajikistan is one of the world’s great new destinations. The capital of Dushanbe shines like a lighthouse in troubled waters. Restaurants and Western-style cafes are popping up around town. The people have held onto their proud Islamic culture and the streets and countryside are safe.

Tajikistan’s biggest calling card, however, can be seen from all over the country. Ninety percent of the nation is upland. Mountains provide bookends from the Fan Mountains in the West to the Pamirs in the East. The Pamirs are also where Marco Polo followed the Silk Road and gave name to the sheep who number nearly 24,000, making Tajikistan home to one of the largest wild sheep populations in the world.

It’s also dirt cheap. Taxis across Dushanbe are 3 euros. Beer 1 euro. Lunches 2 euros. Five-hour taxi rides 9 euros.

Greeting me in Dushanbe after my flight from Almaty was Jaf Asimov, a 42-year-old IT wiz who owned my lovely AirBnB in the heart of the city. Short, handsome, with a wisp of gray hair, he spent a year studying at Ohio State and lived through Tajikistan’s bloody civil war.

Like most people who grew up under communism, he’s seen more than he wanted to. Upon my arrival by taxi, he accompanied me on a perfect 75-degree evening about three blocks to Bundes Bar, in a group of glittery, modern bars in an area downtown. We took a table outside and I ordered an ice-cold beer. I told him my plan.

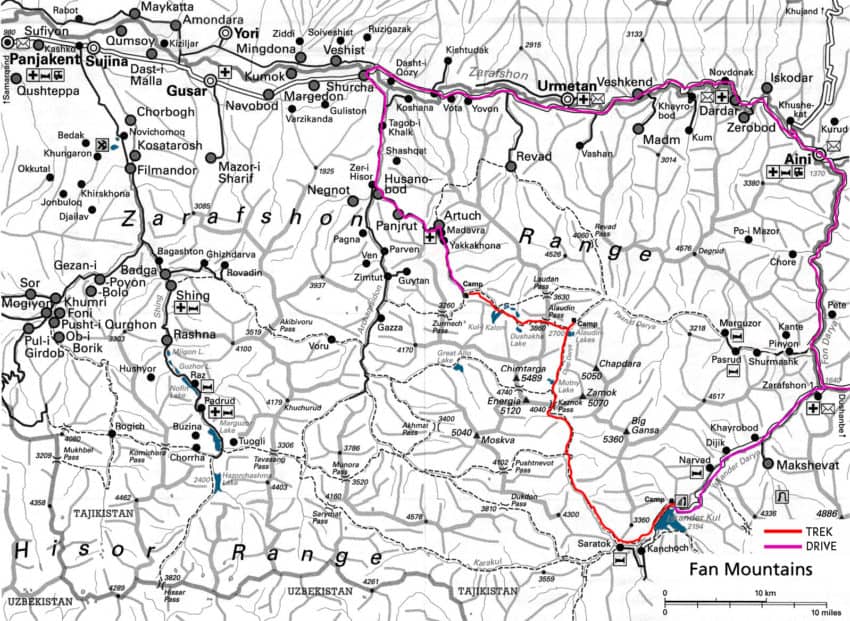

I wanted to wing Tajikistan. I had no reservations. I wanted to kick back in Dushanbe for a couple days then hit the trail again, this time in the challenging Fan Mountains. I asked about contacts and beautiful hiking trails. Turns out, Jaf is as connected as any travel agency in Dushanbe. Within an hour and three or four phone calls, he had arranged for a taxi to the jump-off town of Penjikent, a homestay in Penjikent, an off-road vehicle into the mountains and a four-night reservation in Artuch.

The hospitality of the Tajik people I’d read about was in full display across the table from me.

I asked him what I should expect from my third country on this trip.

“It’s the most friendly country in Central Asia,” he said in perfect English. “People are nice here. Nature is nice. We have clean air. It’s not polluted. We have fresh, organic fruits and vegetables and meats, which are very rare and expensive in developed countries like the U.S. and Europe.

“Life here is good.”

He acknowledged that the unemployment rate is high and about a million of Tajikistan’s population of 9.2 million have left the country to find work. But while Tajikistan remains poor, its growth rate is high at about 2 percent a year.

I asked him what he remembers about life in the USSR. Continuing a theme I found all through Central Asia, his memories weren’t bad.

“We lived in one big country,” he said. “We didn’t have any borders. We didn’t have any visas with other regions. We didn’t have visas with neighboring countries. Traveling was easy from one city to another city. Education was much better.”

Today, like many former communist republics and countries, life in the city rocks while life in the country rots. Tajikistan is no different. Dushanbe is one of the many ex-communist capitals that has been polished up, propped up and illuminated. Like Prague, Ljubljana, Tallinn and many others, Dushanbe is immensely walkable.

I woke up on a sunny 75-degree May day and walked up the street to Tapioca, a cute, wood-polished cafe with spacious outdoor seating. A blackboard advertised margaritas and cuba libres. Another sign read, in English, “Why sleep when there’s coffee?” I had a pretty good cappuccino and a very good omelet while a chorus of birds sang next to a street with little traffic.

Welcome to free enterprise, ex-Soviet style.

A couple blocks farther is one of the prettiest parks I’ve seen in the old Soviet bloc. Rudaki Park is covered with flowers, particularly roses, with fountains and towering monuments. An army of headscarved women wearing way too many clothes under the beating sun painstakingly landscaped every pile of dirt and blade of grass.

As I entered the park, a traffic cop screamed at motorists to keep moving. Another cop saw me pull out my camera and in no uncertain terms told me the same. A government ceremony was being held in front of the 25-meter gold statue of Ismoil Somoni, the national hero who in the 10th century founded the Samanid dynasty which eventually became Tajikistan.

I got closer and it looked as if Somoni was holding up a middle finger, toward Russia. Alas, it was just Tajikistan’s national symbol: a crown under seven stars representing the Tajik heaven of seven mountains and seven gardens.

On the other side of the park, behind a ring of five fountains and under a graceful, beautifully tiled arch stood a statue of Rudaki. Considered the greatest poet in the history of the Persian language, Rudaki was born in the 9th century near the Fan Mountains and is among Tajikistan’s heroes.

No writer in Central Asia ever captured the plight of his people better than Rudaki:

Look at the cloud, how it cries like a grieving man

Thunder moans like a lover with a broken heart.

Now and then the sun peeks from behind the clouds

Like a prisoner hiding from the guard.

***

The sun didn’t creep behind any clouds on this day. The sky had no clouds. The heat had picked up into the high 80s. The previous week in Kyrgyzstan I kicked myself for scheduling this trip so early in spring, before the snows melted. But as I walked the hot, dusty streets of Dushanbe searching for food, beer and air-conditioning, I was so thankful I didn’t come later.

In summer, Central Asia is an oven.

I searched for typical Tajik food. I doubt anyone outside Central Asia has ever uttered the phrase, “I’m in the mood for Tajik.” But I did. Jaf recommended Toqi, a prototype Tajikistan restaurant near Dushanbe’s Shah Mansur Bazaar, a bustling public market where I picked up 200 grams of sugared almonds for about 25 cents.

Up a hill from the market and near a dodgy neighborhood, Toqi has three trees growing inside the restaurant, up and through the roof. It was Ramadan, Islam’s monthly fast, and restaurants in Muslim countries die from sunrise to sunset. I walked in mid-afternoon and a posse of bored waiters and waitresses sat around for the few May tourists to enter.

I wasn’t real hungry. The heat and my maddening Maps.me sapped my appetite. But Toqi is as Tajik as reading a Rudaki poem by a mountain stream. No English is spoken. No English menus are offered. Without looking I ordered Tajikistan’s national dish, kurotob. It’s a piece of flat bread covered in tomatoes, onions, chopped parsley and coriander with a yogurt-based sauce. The young waiter came over with his iPhone on Google Translate showing me the message “with meat?”

I expected a little snack, kind of like a quesadilla. No. It was a Denny’s size portion the size of an entire dinner plate piled about two inches high with food. Intimidated and not very hungry, I still dug in. It was fantastic. The bread was soft and kind of cheesy. All the vegetables were fresh and the beef was lean.

Ramadan is a great time to visit Islamic countries. Not only do you not need a lunch reservation, get invited to a local’s home after dark and the food intake is massive. That night Jaf invited me to his home not far from the old presidential palace where in 1992 anti-government demonstrators, furious at the old communist guard still ruling the country, stormed the building and took hostages. Today it is a dark edifice with nary a light on, looking more like a true haunted house than anything close to a palace.

We walked along Rudaki Park with seemingly half of Dushanbe. Men and women strolled together. Kids laughed. Mothers rolled their strollers. The bright lights of the park’s monuments were to our left.

So was the president’s motorcade. We heard sirens and Jaf said it’s an announcement for everyone to get away from the street. The motorcade was taking president Rahmon to his home. I saw a fleet of black cars speeding up the road and I walked across some dirt of a garden to get a closer look.

“John! Get back from the road!” Jaf said. “Otherwise we are in trouble!”

Jaf, separated with two children, shares an apartment with his father and sister. Nigora is the most westernized of the trio. She married a British soldier cursed by being stationed in Londonderry, Northern Ireland. And she thought life in Tajikistan was stressful. Their dad, Muzaffar, is 70 and walks 10 kilometers a day. He looks like an old hippy, with a laid-back nature and long, white hair cut in a bit of a bowl.

“I cut it myself,” he said unabashedly. He worked in computers for the USSR in the ‘60s and even studied at what is now Moscow State Technical University, one of the top tech schools in the world. He said they had competitions against MIT “and we beat them all the time.”

Nigora brought out a pile of pancakes with sour cream and apricot extract and a plate of sweets. Then came tea and coffee. Just a couple of blocks and 27 years after blood spilled in the streets, Tajikistan opens her arms again.

***

The town of Penjikent (pop. 35,000), once a major stop on the Silk Road, sits on the far western edge of Tajikistan, a country with a border carved up so much over the years it’s shaped like an amputeed reindeer. Penjikent’s bazaar is teeming with women in traditional head scarves and men in tunics selling everything from wheel-sized bread to cheap clothes. With a mosque across the street, it has the air of a Moroccan medina.

It’s here I met Akmal, my host for the night and driver the next day, and Bahodur Rahmatilloev, my 19-year-old guide, translator and all-around fixer. Bahodur is a real bright university student with tons of ambition and, in my case, patience. His father runs Penjikent’s driving school. The school’s perfect driving lot, complete with bright lane markings and stop signs, was one of the few good roads I saw in all of Tajikistan.

My room in Akmal’s home, a spacious, airy place down a gravel alley, was a giant prayer room with a rug and a cot. Akmal told me an odd time to eat dinner: 7:40 p.m. Who says 7:40? Why not 7:45 or 8? I went into the dining room and saw a massive display of food that could feed the Red Army. With Akbar, Akmal’s nephew, there were only four of us.

“Go ahead and eat,” Akmal said in Tajik through Bahodur. “We have a few more minutes.”

The entire country has a calendar showing what time is officially sunset and it gets later every night. That night was 7:57. So I ate and ate and ate. And I barely made a dent in the food.

The list was exhausting. First there was a plate of pirashki, fried bread filled with meat, onions and a little oil. Then Akmal brought out a huge bowl of oshi turush, soup made with rice, grasses and chaka, a milk-based grain. Kind of sour but not unpleasant. Then came a heaping plate of macaroni with meat which was good but I was way too spoiled in Italy to appreciating it. They offered a mountain of tut, white garbanzo beans which I couldn’t touch.

Then they had a big bowl of navot, big chunks of what looked like hard orange candy. You put it in your tea to sweeten. By this time I needed a digestivo or I’d fall into a food coma. I couldn’t move. This isn’t mentioning the bowl of fresh cherries, big plates of onions, tomatoes and peppers and a giant plate stacked with plate-sized rolls.

“You eat like this every night?” I asked.

“Only during Ramadan,” Bahodur said. “Normally we eat very simply.”

After dinner as I spent 15 minutes trying to stand, Akmal went to the corner of the room and prayed. He didn’t say anything but with his back facing us he bent down and touched his head to the ground about five times. After 10 minutes he was back. They all pray five times a day and usually get up at 3 a.m. just before sunrise to eat a big meal to last them all day.

“Are you hungry?” I asked.

“Not really,” Bahodur said. “The first two or three days it’s difficult but this is our 17th day.”

Akmal had lost three kilos already. For me, however, it was good carbo loading.

I would be hitting the mountains the next day.

***

Hiking in Tajikistan isn’t like it is in Europe where I live or Colorado where I lived. The hiking culture in those places is centuries old and the trail system is as organized as German trains. The L.A. freeways have fewer directional signs.

In Tajikistan you see the top of a mountain and hike toward it. How you get there is up to you. Which is why I found myself looking up a 75-degree grade at a 600-meter climb with no trail in sight. On one side seemingly straight up sat loose shale. On the other side were bushes.

About 30 feet ahead of me stood Bahodur, in a pile of loose rocks, surveying Mt. Chuarak, a mountain of 3,300 meters which hovers over our camp like a night watchman. It’s tall, rounded and craggy and sits below two beautiful snow-capped mountains.

I started to climb. My feet slipped immediately. I fell on my hands. I went a few more feet. I fell again.

“This is impossible!” I said. “I can’t climb this!”

“I think we should go this way,” he said.

He pointed left to the bushes. I saw no path, let alone a directional sign. But my feet didn’t slip. Fortunately, it hadn’t rained that morning and it was relatively dry. However, the incline was brutal. I went up, grabbing bush branches for leverage. I stopped after about 10 meters. I looked up. The top looked no closer. My breath was coming in heaves.

“Bahodur, this is really steep,” I said.

“Take your time,” he said. “We have all day.”

I climbed another 10 meters. I saw a flat rock. I stopped again. I noticed Bahodur wasn’t even breathing.

“You aren’t tired?” I said, gasping.

“Not yet.”

I kept going. I saw another flat rock which by this point started looking like a lounge chair. I looked up. Still, the top could not be seen.

“Bohadur,” I said, “I don’t know if I can do this.”

“Yes, you can. Just take your time.”

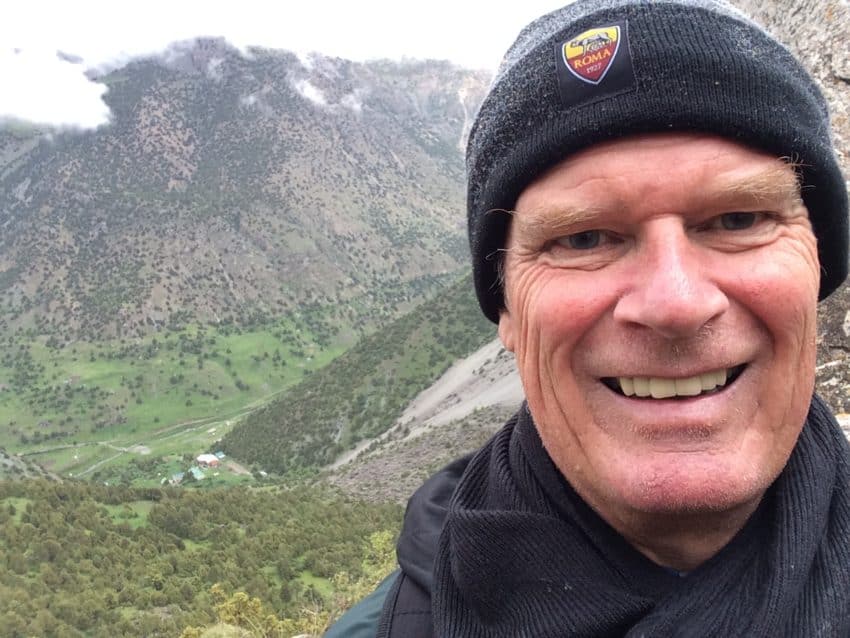

Again, I trudged up. Then I saw something that kept me going: The view behind me. The lake that we had passed on the way to the climb was absolutely breathtaking from above. A turquoise lake set in front of a backdrop of snow-covered mountains. I could only hear birds chirping and a distant cascading river. No other person was within miles. I was definitely at the back of beyond.

I caught my breath and kept going. Another 10 meters, another stop. Then Bahodur got excited.

“Look, Mr. John! We’re almost there! See that rock?”

Wearily, I looked up. I saw a big round rock about 20 feet set between two outcroppings from the mountain. It looked about 100 feet up.

“That’s the top!”

I looked below me. Behind the lake I could also see another. Both lakes were superimposed against a range of snowy mountains. It looked like a tapestry. I needed to take that photo.

I got up and made a determined mad dash to the top.

“You made it!” he said.

Breathlessly, I gave him a hearty Tajik handshake, with my left hand over his wrist.

“FINALMENTE!” I yelled in Italian.

The view behind me wasn’t as great as 100 feet below. A giant boulder prevented me from seeing the other lake. But the view on the other side made up for it. Down below — WAY down below — I could see a few tiny buildings and what looked like a little creek.

“That’s our camp,” Bahodur said.

It’s true. That little settlement was the camp from which we began. I felt as if I was in outer space. I ate some cheese and a Clif Bar, both of which tasted like filet mignon.

I told him between inhales of thinning air, “Bahodur, in the future I want you to tell me if you EVER get another 63-year-old to make it this far.”

***

Life in the camp felt very isolated. Internet is awful in Central Asia and particularly bad in Tajikistan. It became worse in May when a prison break resulting in deaths, plus an ISIS scare, made the government shut down social media. I had Whatsapp and that’s it. Between that and the camp’s sketchy food, hiking became the lone source of entertainment.

Fortunately, every day’s trail was better than the last. The two lakes we saw from above were two of three lakes, also called Chuarak, that are just a couple hundred meters apart. Each one sits under a snow-capped mountain and is crystal clear. I could see a steady stream of water cascading down the mountain into the lake. This is the water that babbled past my cottage all day and what I used to fill my water bottle.

On a particularly cold, gray, rainy day in which we couldn’t see the mountains let alone climb one, we set out to explore the village of Artuch 10 kilometers downriver. About 2,500 people are spread along the river for about a kilometer. Shadowing us down the hill through a steady rain were cattle and locals on burros. We surveyed about 100 meters of the river to find a place we could safely ford, my shoe surviving the crossing much better than it did the muddy roads. The village is a ramshackle collection of wood and cement shacks with villagers in surprisingly sharp native costumes, as if preparing for a tourist show.

No. This is the real deal. The only outsiders these people see are climbers and hikers coming through town on badly needed 4-wheel drives.

“A little girl died today,” said Bahodur who asked one of the locals. A funeral ceremony was about to begin.

We saved the best hike for last. Kulikalon lakes are some of the prize jewels of the Fan Mountains. Meaning “big lake” in Tajik, Kulikalon is 2 1/2 hours away from camp. One long hill was followed by a flat plateau followed by another hill. After two hours, Bahodur pointed out toward the horizon. A huge snow-covered mountain that looked straight from a Japanese tapestry stood before us.

“There it is,” he said.

I saw a narrow sliver of green. We walked about 200 meters and there it was: big and green and clear. It stretched for hundreds of meters in front of me and beyond, reaching to the edge of massive, snow-capped mountains forming a perfect white, wintery background. I stood on a rock at the lake’s edge, stretched my arms out, like, yes, this is what life is about. This is traveling. This is Mother Nature at her most unspoiled splendor.

Bahodur looked crestfallen. He said the lake, and the two others nearby, were too small.

“It’s much more beautiful in the summer,” he said. “The snows haven’t melted yet. I’m sorry.”

Bahodur had nothing to be sorry for. Neither does Tajikistan. In a world that is getting smaller, where the Internet makes nations as accessible as the push of an Enter button, this mountainous corner of the world has picked itself up and stands tall to the intrepid traveler. It’s always better to take the trail less traveled.

And sometimes it’s even better when there’s no trail at all.