The Liechtenstein Trail bounces New York Times off my bucket list

TRIESENBERG, Liechtenstein — I’ve always had two bucket lists: one for travel, one for writing. My travel bucket list has shrunk rapidly after 105 countries. My writing bucket list remained frustratingly stagnant, even after retirement 5 ½ years ago. It sat on my computer screen, mocking me like an old boss saying I should find another line of work. I had plenty of time on my hands to knock off goals. I thought I would X-out Publish in a Major Magazine four years ago when Penthouse agreed to buy my story on a hotel in Playa del Carmen, Mexico, that specializes in S&M. Then Penthouse got sold, its direction changed and all I got was a nice kill fee and nightmares about leather-clad women in cages.

I’d tell you the cliche that I could wallpaper the inside of my apartment with rejection notices from The New York Times. But I never received any. I didn’t get a single response. However, my sportswriting background turned me into a bulldog at a young age and now I’m just a stubborn old dog. A year ago, I made a friend who knew someone at The Times who knew the travel editor who put a bug in his ear about me.

The result came May 26 when The New York Times published my story on Liechtenstein along with photos from my girlfriend, the uber-talented Marina Pascucci. My writing bucket list just got shorter, finally.

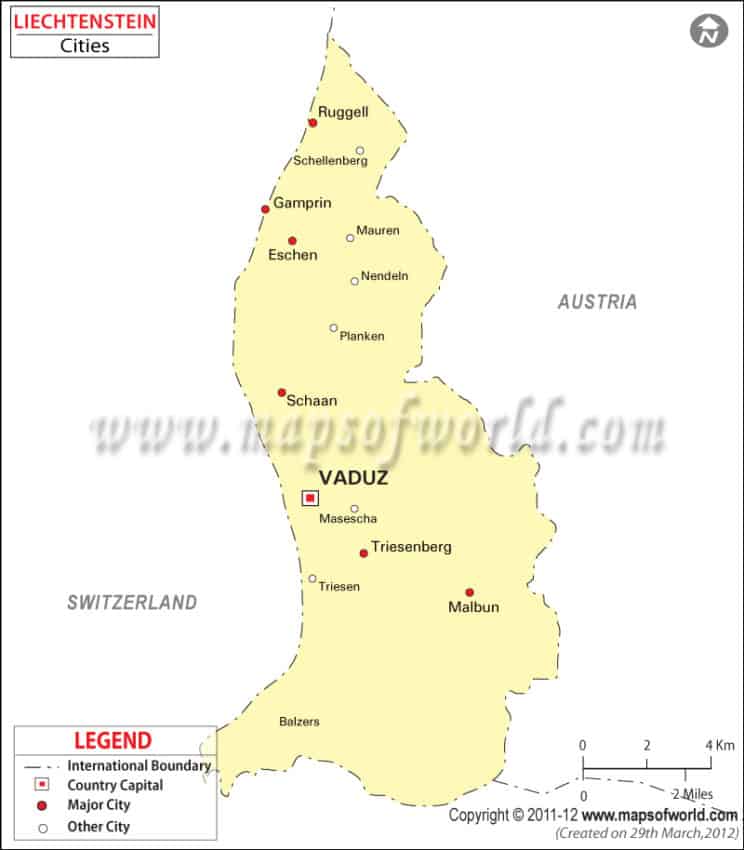

Why Liechtenstein? Where is Liechtenstein? What is Liechtenstein? Good questions, all. I visited and wrote about Liechtenstein in 2016. The tiny principality in the middle of the Alps between Austria and Switzerland was a fall-back destination after a freelance assignment in Austria fell through. Turns out, the fourth smallest country in Europe has more than just beautiful, oversized postage stamps. From the gorgeous, lightly trodden mountains to the cute villages to the great cuisine, Liechtenstein is Switzerland light, the perfect off-the-beaten-path post for the intrepid traveler.

Last year while researching future travel story topics I stumbled onto this factoid: 2019 is the 300th anniversary of Liechtenstein’s independence. Yes, through Napoleon Bonaparte’s wide swath through Europe, World War I and Nazi Germany, Liechtenstein never lost its country. Or its soul.

I called Liechtenstein Marketing for a story angle. Among the year long list of events, they were creating a 46.6-mile hiking trail that connects all 11 cities in the country. It would open in May 2019 and would include an app that gives information and virtual reality visuals of 147 places of interest (POI).

It’s called the Liechtenstein Trail and in October, I was going to be its first guinea pig.

Marina is a gym junkie and not much of a hiker but she loves mountains. I love her photos of mountains. She came along. We had a one-night layover in Zurich then took the train south to the cute capital of Vaduz and a bus to a gorgeous off-season ski resort, Malbun, the only ski resort in Liechtenstein.

Sure, saying I walked across a country, knowing it’s Liechtenstein, is like saying I got published in The New York Times and it was a want ad. I once walked across Monaco. It took 45 minutes. Liechtenstein isn’t that small but it’s all of 17 miles long and nine miles wide. As I wrote in The Times, “It is one cattle farm bigger than Staten Island.” You can drive the length of it in 25 minutes. A middle-aged person with a long-expired gym membership could walk across it in two days and have time for lunch and dinner out both days.

“Many people have only vague cliches about our small country,” Alois, Hereditary Prince of Liechtenstein, wrote in an email. “I hope that the anniversary will help the world to get to know Liechtenstein better.”

Alois, also known as Count Rietberg, is the perfect symbol of Liechtenstein’s friendly, homey, small-town feel. Not many members of royal families in the world can be seen jogging through the streets of the capital, or sharing wine with the public at his own winery or walking the same trails I walked.

The 51-year-old Hereditary Prince, the eldest son of Hans-Adam II, the Prince of Liechtenstein, opens his castle to the public every summer for an annual party. A bigger party occurred Jan. 23, the date in 1719 when the communities of Vaduz and Schellenberg, at the time members of the German state, signed the contract forming the principality of Liechtenstein.

This is heady stuff for the population of 38,000. Vaduz, about as big as some rest stops on Germany’s Autobahn, has all of 5,300 people. Liechtenstein has no airport or military. It has two train stations, two newspapers, one hospital, one TV channel and one radio station.

It also has one very proud boast: It has had the same border for 300 years, something its bigger neighbors can’t claim. In Liechtenstein the only things big are its mountains. This anniversary is bigger.

“Historically, this is the most important event in my life,” said Leander Schadler, 61, a Liechtensteiner historian and hiking guide. “For the people of today’s principality, the (merging) of the earldom of Vaduz and the lordship of Schellenberg to an imperial principality was a fundamental change. My ancestors no longer lived in a German state.”

Liechtensteiners have also waited 300 years to tell the world where they are. Please note: They are between Austria and Switzerland — “not Australia and Sweden” as Liechtenstein Marketing CEO Michelle Kranz often corrects. It’s not just geographically challenged Americans they must educate.

“Good journalists in Switzerland, they don’t know what currency we have,” said Martin Knopfel, Liechtenstein Marketing’s marketing director who developed the Liechtenstein Trail. “They think we have the euro. (It’s the Swiss franc.) This is one of our major tasks: To put Liechtenstein onto the landscape and for us, the 300-year anniversary is a big, big, big chance.”

Before 2019, Liechtenstein was best known for colorful — and large — postage stamps and being a tax haven for companies around the world. Liechtenstein used a low corporate tax rate of 12.5 percent to lure corporations in the 1970s. At one point, 73,000 holding companies were in Liechtenstein. The tax windfall helped give Liechtenstein the third highest gross domestic product in the world behind Qatar and Luxembourg.

In 2008, U.S., Germany and the United Kingdom investigated companies avoiding local taxes by registering in Liechtenstein. Now Liechtenstein is no longer so lenient. It hasn’t hurt the economy. The average annual income is $65,000 and its unemployment rate is 2.4 percent. In fact, there are more jobs than citizens to fill them. About 20,000 people commute daily into Liechtenstein for work, causing what many locals say is the nation’s No. 1 problem: Traffic on the main two-lane road leading into the capital can be a bit slow at rush hour.

That’s it.

“The greatest accomplishment of the last 20 years has been how Liechtenstein has handled the global financial crisis and modernized its financial industry,” the Hereditary Prince emailed. “Liechtenstein has a very internationally oriented economy with a large export industry and an international financial center.”

It also has something that doesn’t make the news: 250 miles of hiking trails. Working with Liechtenstein Marketing, I broke up my trek along the Liechtenstein Trail into five days. I’m an experienced hiker: I’ve backpacked in the Himalayas and the Andes. I climbed Mt. Kilimanjaro. I lived and hiked in Colorado for 23 years. I trekked for five days in Slovakia’s High Tatras in 2014, in the highlands of Laos two years ago, the Caucasus of the Republic of Georgia last year and the Fan Mountains of Tajikistan in May.

But never have I experienced hikes with such variety as Liechtenstein: mountains, forests, villages, farms, rivers — sometimes all in the same day.

“This is the difference between this trail and other long-distance trails,” Knopfel said. “Nature, nature, nature. This trail is really in the heart of Liechtenstein.”

I’m 63 and pretty fit. But despite the trail having a mile in elevation gain, it is for anyone. Those who want to bail, can stop in any village and grab a bus back to their hotel — as Marina did in the two days she joined me.

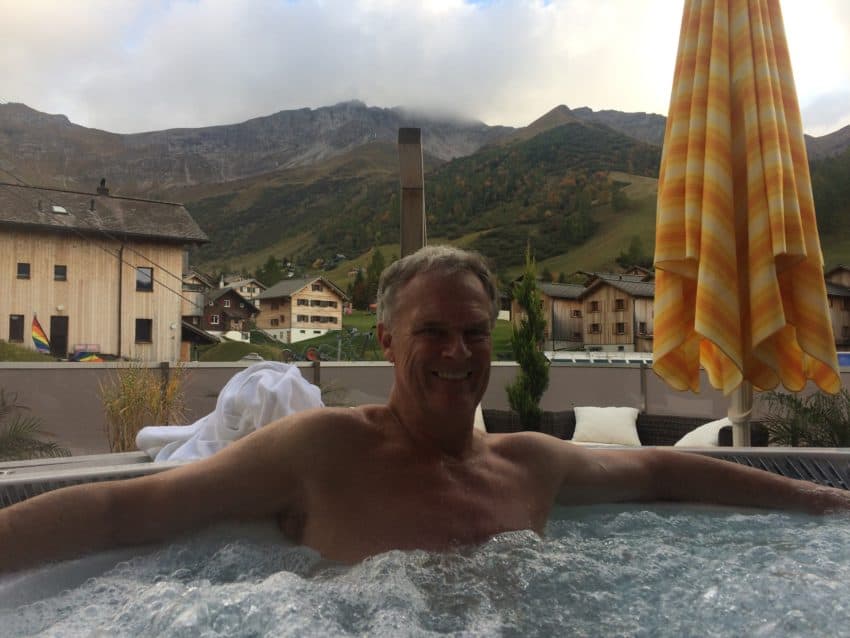

Malbun, our lovely ski resort, sits on the southeast end of the country. It’s a short ride from any town using Liechtenstein’s efficient bus system. And the Jacuzzi, Turkish bath and sauna at the Hotel Turna Malbun were welcome signs upon return each day.

Here’s what makes the Liechtenstein Trail unique to the world: No need to pack a lunch. Because it connects all 11 towns, you can always drop your backpack at one of the plethora of restaurants. I never did. I wanted to cut costs. But I often walked past people sitting outside in the sun digging into kasknopfle, Liechtenstein’s national dish. It’s a big pile of short noodles covered in two cheeses and shaved fried onions. It’s great fuel for hiking up your next mountain if you don’t fall into a food coma first.

The Liechtenstein Trail officially opened May 26. In October, pre-app, I marched off feeling a bit naked using Liechtenstein Marketing’s stack of trail maps and my cell phone’s iffy GPS. With only a few wanderings astray, on sunny October days in the high 60s, here’s what I found

DAY 1 — Balzers to Triesen to Triesenberg: 8.6 miles, 1,970 feet elevation gain, 5 hours, 15 minutes.

I stood on the edge of the border town in the shadow of a 12th-century castle high up on a hill. Above the castle the craggy brown peaks of 7,200-foot mountains faced another series of peaks on the other side of me. The only sounds I heard were birds chirping. The rural village road had nary a car.

Schadler met Marina and I in Balzers on the east bank of the Rhine across from Switzerland. The 12th century Burg Gutenberg castle is the first POI on the trail. Schadler explained that it belonged to Austria until 1824 when the community of Balzers purchased it and eventually turned it into a museum which it remains today.

Schadler is the authority on Liechtenstein history and hiking. Short, stocky with short gray hair, he peppered the day’s hike with an oral history of Liechtenstein. It began as the Earldom of Vaduz then became absorbed by the German state and the Holy Roman Empire. The German Reichstag felt that Schellenberg was too small to be a member so it joined with Vaduz to form Liechtenstein, which, in German means “light stone” for the color of the five castles that dot the landscape.

“There was a time when Liechtenstein was very, very poor,” Schadler said. “Armies were always going through the Rhine Valley and they took everything they could receive.”

During World War II Switzerland protected Liechtenstein and Adolf Hitler never invaded. “Maybe he had too much money in Switzerland,” Schadler said, half jokingly.

Balzers is a postcard-pretty town with bright white fences, vine-covered houses with a plethora of maple trees and a small creek running through it. We walked through town on deathly quiet streets then followed the Rhine until Triesen, Vaduz’s “suburb” to the south.

The trail then heads east and uphill, in parts, seemingly straight uphill. The steep trail to Triesenberg at 2,952 feet passes through beautiful green meadows with dairy cows whose clanging bells were about the only sounds we heard. We walked by dirt fields ready for farming. The trail turns to a dirt service road that is conveniently blocked off for foot traffic and mountain bikers.

A sign on one of many trash cans in the forest reads, “Don’t make noise in forest. Think also of animals.”

We passed a small alpaca farm where alpacas graze near a self-service souvenir shack selling everything from cheese to llama wool. You look at the price and leave the money in an open cash register overflowing with money. I bought my nephew’s wife some alpaca wool gloves for Christmas and used the credit card machine to pay. Yes, Liechtensteiners are a trustful lot.

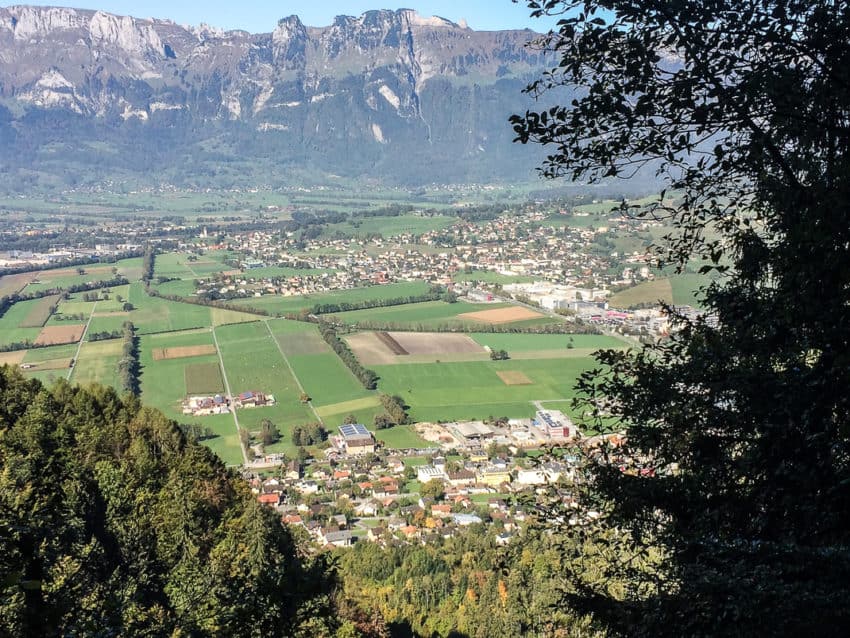

Between cuts in the trees are spectacular views of the Swiss Alps, all brown and craggy and imposing. Below are the tile roofs of Balzers and Thiesen peppering the landscape. Park benches are strategically placed at each vista. As I would learn, around every corner is a new view of this lightly trodden country.

All day we only see five people, all joggers.

Day 2: Triesenberg-Vaduz-Schaan, 9.3 miles, 1,970 feet elevation gain, 7 hours.

Knopfel met us at 8:30 a.m. at Triesenberg’s post office. Triesenberg, the highest town in Liechtenstein and the closest to Malbun, rests on a mountain with brightly painted houses sporting vegetable gardens and private vineyards and flower boxes with purple, white and pink flowers.. Grapevines hang over front doors.

Knopfel, 42, is a Liechtenstein native and lifelong hiking enthusiast. After Schadler led me through some thick forests and forks in the trail with no signs up yet, I asked Knopfel what should trekkers bring to Liechtenstein.

“What they should do is before they come here, download the app so they have it on their phone,” he said. “Once they are here, they don’t need Internet connection because the app will know your position by the GPS.”

Day 2 was mostly downhill but no less beautiful. The main road that snakes its way up from the valley to Malbun has lookouts near cows grazing in meadows. Below I could see the town of Triesen, churches, the Rhine and the Swiss Alps beyond.

The path starts out steep into a forest and past little farm houses before we came to the day’s first Point of Interest: a rock. It looks ordinary, only five meters long and 4 ½ meters wide. However, it is 400 million years old, left over from a prehistoric glacier that 18,000 years ago stretched 35 miles into Germany.

We continued through the forest and, this being October, the leaves had turned to yellow, orange, green and red. It isn’t Vermont but add the view below of Vaduz and the Swiss town of Buchs on the other side of the Rhine and you may not find a better view of fall colors in Europe. I saw all of three hikers.

As the mountain trail descended into a clearing, Knopfel told me this is the trail the Heredity Prince can often be seen. Then I knew why. Greeting us as we emerged from the trees was the princely family home: Vaduz Castle. If a 12th century castle can be unassuming, this is. While it looks majestic with its many A-frame roofs, tower and turrets, it sits directly above the capital. You can walk to it up the main windy road from downtown like a local market.

It has been in the family name since 1712 and their primary residence since 1938. I walked by the gated entrance, framed by ivy, as if walking by a neighbor’s. The castle isn’t open to the public, except one day a year, but Knopfel’s office negotiated with the princely family to include photos of inside the castle on the app.

We passed the castle and dropped into downtown Vaduz (Va-DOOTZ), where we stopped at a carnival and had bratwursts on brown bread for 5 Swiss francs (about $5), an absolute steal in a country with prices higher than Switzerland.

Vaduz is a small-town capital, with a walking mall lined with restaurants and boutique shops but that all but closes down at 8 p.m. I asked one local what you do at night in Liechtenstein and he said, “Go to Austria.” However, Vaduz also has the most Points of Interests. On the main road we walk by the Kunstmuseum art museum, the Postal Museum, the National Museum and garachly yellow brick Parliament building.

Knopfel led me back up the hill past the ultra-rich Park Hotel Sonnenhof with a beautiful view of the castle from the gazebo and back into the forest. We eventually descended into Schaan, abrutting Valduz to the north and Liechtenstein’s largest city with a whopping 6,300 people. We stop near the bus stop for a well-earned beer.

After two days of going up and down nearly 2,000 feet, my legs were feeling the first signs of fatigue. Marina, whom I took to North America in August, told me, “I think I lost the two kilos I gained in the United States.”

“I have journalists and they say, ‘Oh, I’m a hiker and all physical and we should go on all the tracks,’” Knopfel said. “Then they say, ‘Oh, I didn’t think Liechtenstein was so big.’”

Day 3, Schaan-Planken-Nendeln-Eschen, 10.6 miles, 820 feet elevation gain, six hours.

Schadler picked me up at my hotel and we drove to Schaan and walked through a string of businesses and past the 19th century Church of San Laurentius, another POI. I noticed there is no garbage. I remembered in Vaduz seeing a woman light a cigarette and walking 50 feet to put the match in a trash can. My street in Rome has so much garbage it looks like an alley in rural India.

Liechtenstein’s trails leading back into the highlands are spotless. Schadler says Liechtensteiners are particular about leaving the country the way they found it. We climbed high into the forest and he pointed out an example: A long expanse over a major drop off to the forest beyond. The country proposed building a 180-meter bridge for $1 million for easier access.

The citizens voted it down and leave it as it was, Schadler said, “No good for the forest, no good for the animals.”

The forest led uphill to the town of Planken, home to large, poster-perfect houses all lined with red shutters and flower boxes in full bloom. It’s also home to the Wenzels, Liechtenstein’s first family of skiing. Between Hanni and Andreas they have won five of Liechtenstein’s 10 Winter Olympic medals making the country, they proudly point out, No. 1 in the world in Olympic medals per capita.

We switchbacked down into Nendeln, walked through town where Schadler left me at a bus stop and told me I could walk to Eschen’s post office at the end of the trail just down the road. We said goodbye for the last time as the final two days it’d just be my maps and GPS.

I was on my own.

Day 4, Eschen-Bendern-Gamprin-Ruggell-Schellenberg, 14.3 miles, 1,640 feet elevation climb, 5 1/2 hours.

We made a mistake.

The day before we were supposed to walk around Eschen, not make a beeline to the post office. Backtracking, I had to hike the steep, quiet residential streets of this otherwise industrial town for an hour, not a good way to start my longest day on the trail. However, the sun had just come up on almost a panorama of mountains and the dairy cows eyeing me lazily as I walked by a meadow gave me an early second wind.

Eschen represents what the Hereditary Prince mentioned as one of Liechtenstein’s great achievements. It’s the headquarters for numerous multinational companies such as Thyssenkrupp Presta, an auto systems manufacturer.

The trail led to Bendern on the bank of the Rhine, noticeably shallow from the lack of rains in the fall. So shallow, I saw a man sitting on a sandbar nearly in the middle of the river.

In the mid-50s and sunny, the weather couldn’t have been better as I meandered through Ruggell, wedged between the forest and the Rhine and where an old man took a pole to knock down apples from his huge tree.

From Ruggell I walked across expansive farmland and the length of a forest before ascending through a 100-foot canopy into a clearing. Here I saw Schellenberg’s claim to fame. Liechtenstein was part of the Roman Empire and in front of me stood a Roman ruin, complete with a round stone oven and lookouts over Ruggell, the Rhine and the Swiss Alps.

For a Roman soldier, this wouldn’t be a bad outpost.

Day 5 — Schellenberg-Mauren-Schaanwald, 6.8 miles, 820 feet elevation gain, 6 hours.

My last day may have been the most beautiful and the most exasperating. Rising early as I had to catch a flight out of Zurich that night, I found myself high above Schellenberg. At 9 a.m., as I climbed through farmland, a sea of clouds had settled under the mountains beyond. A velvet blanket formed the perfect backdrop for small, lonely farmhouses in the fields.

Inspired that I’d seen it all, I began double timing it to the Austrian border and the trail’s end. However, my cell phone’s GPS failed me. It couldn’t match up with the maps and I wound up asking directions in the town of Mauren three times and backtracking twice. When I finally made it across a huge green field into Schaanwald, I could not find the entrance to my last forest walk.

Fighting the desire to see if primal screams echo in the Alps, I called Knopfel who sent me on the right course. However, I took the wrong exit out of the forest and when I found the Austrian border, I had entered on the Austrian side. I missed one side street.

Still, I ventured 50 feet back across to Liechtenstein, turned around and snapped a memorable photo of the border sign and the end of my, ahem, cross-country venture.

Since the trail opened on the day my story appeared, Marketing Liechtenstein reports that more than 10,000 people have already hiked it. Did my story spoil it? No. In this Internet age, the world has no secrets. It just has more people with more information. Liechtenstein won’t change anytime soon.

Three hundred years of independence will do that.

July 12, 2019 @ 10:31 am

John, your story on Liechtenstein and its trail have inspired me. I now want to go there and make the trek

April 21, 2023 @ 5:37 am

Looking at doing two days on the trail, and I come from a flat, low elevation state so two days that are the prettiest but also good for a novice hiker. What areas should I do?