Traveling in Italy: Trip to Puglia reminds me of why I live here but caution flags rise

Summer tourist wave may become dangerous

SELVA DI FASANO, Italy — The first sign that traveling in Italy this summer has radically changed came when we took the airport shuttle from the parking lot. It had only one other passenger. We went through Rome’s airport security with no one in front of us. The corridor from security to our gate was empty, a long, wide hallway void of people, voices or noises. It could’ve held an archery tournament.

Rome’s Fiumicino Airport, the eighth busiest airport in Europe, averages about 40 million passengers a year. In May it had only 109,000. You do the math.

Welcome to travel in Italy coronavirus style. Marina and I took our first trip together in 2020: a weekend in Puglia, the heel of Italy’s boot. It was rescheduled from our anniversary trip we cancelled in May. That came in the middle of Italy’s three-month lockdown where Italy’s 60 million people joined minds — if not hands — and hunkered down to flatten the curve.

It’s what the U.S. should’ve done but instead opened businesses and beaches and millions of Americans reacted like over-sexed rats let out of their cage. Now their apocalyptic nightmare gets worse every day and they’re banned from the entire European mainland. The U.S. is toxic. No American can do what we did: Sit by an Olympic-sized swimming pool high in Puglia’s hills, swim in the royal blue Adriatic Sea and aimlessly stroll through sun-splashed historic villages on the list of Italy’s Most Beautiful Towns.

I wasn’t nervous about flying for the first time since the end of February. Italy is flattening its curve. Its number of actual positives (total cases minus deaths and recovered) has gone from 108,257 on April 19 to 12,919. In the U.S. it has gone from 658,270 to 1,803,381. In the last two weeks, Italy has averaged only 197 new cases a day and 15 deaths. The U.S., with only five times the population, has averaged 52,800 and 579, respectively. The U.S. has 4 percent of the world’s population yet a quarter of its deaths and total cases.

Italy is not only separated from the U.S. by an ocean. It’s separated by a mentality.

The arrival

Precautions in Italy are everywhere. Arriving in Rome’s airport we had to bring a form listing our contact information and if we’ve been in contact with anyone contagious. Our temperature was taken as we arrived at Fiumicino and after landing in Bari. Anything over 37.5 celsius (99.5 fahrenheit) you’re turned away. Our hotel had signs requiring everyone to wear masks in the common areas. Hand sanitizers were everywhere. Everyone complied.

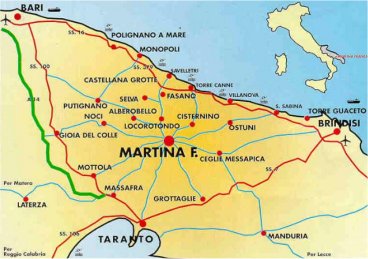

I’d been to Puglia twice before. It’s the one Italian region too many Americans overlook. It’s too far from Americans’ Venice-Florence-Rome triangle. Few speak English. Americans can’t even pronounce it. Puglia (POO-lia) has 240 miles of coastline and three national parks with thick forests dropping down into the Adriatic where secluded coves lay around every bend. One spring, I saw wildflowers of yellow, red, orange and pink lining roads leading to sandy beaches that are almost empty until June.

Bari, a 50-minute flight from Rome, has a refurbished old town. Lecce, 90 miles south near the southern tip, has 40 Baroque palaces. That spring, I went farther south to Otranto where I dined next to a church holding 700 skulls and skeletons of locals slaughtered by the Turks 600 years ago.

Yes, Puglia’s beauty is belied by a violent past. Sticking out in the Adriatic Sea like the thumb of a naive hitchhiker, it has been invaded by the Turks, Romans, Greeks, Normans, Swabians, Venetians and Spanish.

Now it is invaded by Italian tourists.

Selva di Fasano

Italy’s ban on U.S. visitors has made a notable difference in Rome where 1.3 million Americans visited last year. I actually find seats on subways and buses. Restaurants aren’t close to full. But the ban has had little effect on Puglia where Italians flock to its beaches every summer.

Italy lifted its domestic travel restrictions June 3 and Puglia is as crowded as ever. We did our best to avoid it. Instead of rebooking our hotel on the beach, I found another high above the fray. The Hotel Sierra Silvana is in the village of Selva di Fasano. Home to only about 300 people, Selva di Fasano is at nearly 1,400 feet and four miles up the hill from Fasano where many of its 40,000 residents head up the hill in the summer to escape the oppressive heat.

Like now.

It’s about 90 degrees with 40 percent humidity in Puglia and our hotel’s Olympic-sized pool made flying to Bari an alluring necessity. Selva di Fasano, an hour south of Bari, is about a 5 1/2-hour drive from Rome. Our flight left Rome at 9:15 a.m. and we were poolside by 12:30 p.m. We sat at a pool with a backdrop of Mediterranean pine trees and I counted all of 12 people poolside.

Laying there reading my Dick Francis detective novel, with Marina by my side in the bikini I bought for her birthday, the coronavirus may as well be plaguing Mars.

We could tell Selva di Fasano could be an episode in “The Lives of Puglia’s Rich & Famous.” The hamlet is littered with grand villas in the shade of oak, pine, fig, chestnut and walnut trees. A brick pedestrian street passes a little square where we drank wine and a macelleria (butcher shop) that served succulent roast meats to the public.

It is home to numerous pop concerts and is a summer escape for Italian celebrities. Gina Lollobrigida was a frequent visitor.

Like much of Puglia, Selva di Fasano also has peculiar architectural wonders. Strange little round houses with tall brick roofs as pointed as a wizard’s hat dot the landscape. These trulli, none built later than the 14th century, were homes to shepherds and farmers who tilled the farmland that once covered most of Puglia.

Our hotel even offered us our own trullo but with no windows, it’s dark as a coal mine. We opted for the king-sized bed with the balcony and mini-bar.

Dining in Selva di Fasano

Any town of 300 people has limited dining options but Selva di Fasano’s is the only one you need. La Grande Quercia (The Big Oak) is a spacious restaurant-pizzeria where we walked past grape vines and fig trees to sit outside next to huge potted plants.

All the tables were two meters apart and packed with families. Puglia is no place for single people. It’s for couples and families with numerous children, still a common sight this far south in Italy. Between the screams of children and frazzled parents trying to eat, I had a terrific laganari, a round, brownish, robust pasta native to Puglia, with sausage from Italy’s sausage capital of Norcia and sun-dried tomatoes. Marina had homemade orecchiette, Puglia’s more-famous ear-shaped pasta, with fresh tomato sauce and basil. With a half liter of local Pecorino red wine and berry crostata di frutta (small pie squares filled with fruit) on the house, our total bill came to only 25.50 euros (about $29).

I asked the waiter how many foreigners he had seen at the restaurant. “Nessuno, (No one),” he said.

However, the next day, we learned even Italy has limits to social distancing.

Puglia’s beaches

Our hotel has a private beach accessible by van at 20 euros a person. It’s a bargain considering the cost of parking, lanais chair with umbrella and avoiding the colossal hassle of finding a Puglia beach with space in July.

The hotel van wound down the hill to Hotel del Levante in the beach town of Torre Canne. This stretch of coast is where Italy, considered a model in Covid-19 fighting, morphs into Florida during spring break or Alabama’s Gulf Coast.

Young staffers scurried around in lime green T-shirts greeting visitors in the spacious lobby. They set us up with lanais chairs and an umbrella, a solid two meters from all the others. The Adriatic beyond the wide swath of fine, golden sand was clear royal blue and the perfect temperature on a 90-degree day. Marina and I read our books, talked about how fortunate we are living in Italy and got tan.

Then we took a walk.

Our beach was framed by public beaches. It was cheek to cheek, jowl to jowl flesh. Families. Grandparents. Teenagers. All packed together so tight I had to strategize to avoid tripping onto someone’s lap.

No one wore a mask.

Then again, neither did I. We wore one to the beach but took it off once settled. However, my reasoning wasn’t based on one yahoo in Alabama who said, “The president doesn’t wear one. Why should I?” It was based on sitting in the hot sun wearing a mask for two to three hours. Bad excuse? Absolutely. But I corrected it in a hurry.

After about a 10-minute walk past arguably the most crowded beach of my life, for the first time since the coronavirus came to Italy in late February I became worried. I took Marina, equally concerned, and escaped to the covered snack bar behind the beach. I ordered a caprese salad and beer and asked Fabio, the 24-year-old man behind the counter, how worried he was about so many people without masks or distance.

“When I go out to the pubs, I wear a mask,” he said. “I put one on here when I know I have to get close to people. It depends on where you are. It’s safer here than in other places.”

The numbers confirm it. Puglia has 4 million people and in the last two weeks has had a total of seven cases and two deaths. Oklahoma, with a similar population, has had 6,633 and 35, respectively.

However, Saturday was considered the first day of Puglia’s summer and the first day its beaches filled to the break wall. How many people did we pass from Lombardy, Milan’s region which has recorded 49 percent of Italy’s deaths?

Marina and I packed our stuff and spent the rest of the afternoon at Levante’s beautiful and nearly empty hotel pool.

Puglia villages

Already having our fill of Puglia’s beaches in July for one lifetime, we hopped in the car Sunday and explored. Getting up early before the heat and tourists, we rolled into one of the most peculiar towns in Europe. Alberobello is where the trulli are showcased like tulips in Holland. This town of 10,750 has 1,500 of these cute, little tower houses, all stretching up a hill like a neighborhood of Lilliputians.

This UNESCO World Heritage Site is also a major tourist trap. Hordes of tour buses roll in during the afternoons disgorging tourists who crowd onto a lookout near the main piazza and shoot a landscape full of pointy, stone towers.

Arriving early, we were invited into a model trullo where a couple gave us a brief tour — very brief. The woman lived there as a child and many live in them today. It’s cool in the summer and warm in the winter, they say. A small refrigerator stood in one corner. A double bed was under an arch tucked in the back. A curtain hid the bathroom, very small but big enough for the Italians’ ubiquitous bidet.

The man wanted to take a picture of us, his idea of good luck. He showed us pictures he’d taken of Miss Italy and of Marco Materazzi, the famous victim of Zinedine Zidane’s headbutt that led to Italy’s title game victory in the 2006 World Cup.

We walked past the long line of souvenir shops that carried everything from cheap trullo paperweights to expensive trullo paintings and went down the road five miles to Locorotondo. This is what old Puglia should look like: a quiet, white-washed town of spotless streets lined with red geraniums spilling over flower boxes and old men speaking Pugliese dialect in sunny piazzas with panoramic views of the valley below.

It’s listed on the Borgo Piu Bella d’Italia (The Most Beautiful Towns of Italy). More important to me, it’s considered the center of Puglia’s wine scene. We stopped in a tiny takeaway shop for a cassone, a baked roll filled with melted cheese and sausage. We went across the street to tiny To’ Wine Bar where a very enthusiastic bartender named Leonardo sold us a glass of Minutolo, a crisp, fruity white wine from a tiny local vineyard.

At noon, the church bells pealed. A cool breeze came up from the sea below. Three boys kicked a plastic soccer ball against the church wall. Yes, even in July during a pandemic, packed Puglia has quiet slices of Old Italy.

Back in the car, we headed north past rolling farmland, flower-lined roads and white-washed houses. It was like driving through an impressionist painting.

Polignano a Mare

Our last destination brought us to one of the prettiest stretches of coastline in Italy. Polignano a Mare, about 20 miles south of Bari, sits along a craggy coastline pockmarked with caves and coves and crashing waves. We walked through the quiet, steaming downtown to a long, high retaining wall where we looked at the cliffs and the weather-beaten buildings across the tiny street.

The salt in the air and cool breeze felt intoxicating on a day in the 90s. But once we began to wander through Puglia’s narrow streets near the sea, its July negatives resurfaced. Like the beach, the narrow paths were packed. Marina and I were among the few who wore masks. We escaped to a quiet outdoor cafe called Lime overlooking the sea. A message scrawled on a door read, “Questo luogo e’ stato creato prima del paradiso.” (This place was created before paradise.) — Mark Twain.

We ordered panini (That’s plural for panino, Americans.) from Ciro, who just started working after a long three months in Naples. I asked him if he’s nervous about all the people not sticking to the rules that got Italy’s curve down in the first place.

“I think in September and October, maybe (the virus) comes back,” he said. “Of course, I spent three months at home without work, without money. It was too hard. But maybe next year — this year is lost — it will be good.”

We flew home Monday relaxed, tan and well-nourished, filled with wonderful memories of lovely drives, great pasta and fantastic water. But along with a nice bottle of Malvasia white wine and bags of orecchiette pasta, we also brought home some fear. Did any of the virus sneak into Puglia? Did the soft breeze clear it from harm’s way? It takes two to 12 days for Covid-19 symptoms to kick in.

Just as we waited for this trip, we again will be counting the days.

Puglia: If you want to go …

How to get there: Flights from Rome to Bari are 50 minutes and RyanAir has fares starting at $31 euros round trip. Trains from Bari to Fasano are 2 hours, 48 minutes starting at 10 euros, taxis are 1 hour and are about 85 euros. Bus is two hours and 8 euros. Trains from Rome to Bari take four hours and start at 29 euros. Buses take 5 hours, 20 minutes and start at 18 euros. Take taxi from Fasano to Selva di Fasano, about 15 minutes. I rented a car at Bari’s airport and paid 70 euros for three days.

When to go: September. Beaches in Puglia generally don’t open until June. In September the crowds have left and the water is still warm. Daily temperatures drop from highs up to 90 to about 80.

Where to stay: Hotel Sierra Silvana, Viale Don Bartolo Boggia 5, Selva di Fasano, 39-080-433-1322, www.sierrasilvana.com/it/home, info@sierrasilvana.com. Standard rooms starting at 75 euros.

Where to eat: La Grande Quercia, Via Castelluccio 61, Selva di Fasano, 39-080-433-1564, www.grandequercia.jimdo.com, info.grandequercia@gmail.com, 12:30-3 p.m., 7:30-midnight, Wednesday 7:30 p.m.-midnight. Pizzas starting at 6 euros. Local dishes about 9.

For more information: Bari tourist information, Piazza del Ferrarese 29, 39,080-524-2244, www.viaggiareinpuglia.it, 9 a.m.-7:30 p.m.; Info-Point Fasano, Piazza Ciaia 10, Fasano, 39-080-439-4182, www.inforpointfasano.com, info@infopointfasano.com, 10 a.m.-1 p.m., 4-7 p.m., Saturday and Sunday 8 a.m.-9 p.m.

July 16, 2020 @ 12:20 pm

Thanks for reviving my fond memories of Puglia where Lisa and I were in the winter so no crowded beaches- just those lovely and unique trullos.

July 20, 2020 @ 5:53 am

My pleasure, Alice. Tell Lisa she never should’ve left Italy. We’re free here. But get back as soon as you two can.

July 25, 2020 @ 8:24 am

John,

The Americans, one of whom you are, who read your writing are those who are covid aware and responsible, as the majority of Americans are. I doubt any US “yahoo” is reading your stuff.

So please, you need not regurgitate the statistics that we already are aware of and bombarded with by our media. It’s the last thing we need laced through reading about your travels and experiences in Italy. Instead of looking forward to reading your stories I am now dreading getting through them.

Your American readers want to escape the chaos and imagine and look forward to visiting Italy again. And that includes those who do know how to pronounce Puglia.

Thank you and I hope I can get back to enjoying your stories.

Jeanne

July 25, 2020 @ 6:34 pm

The Brindisi / Lecce area is a worthwhile trip, and I’d vote for them over Bari, but that is just my experience.

July 27, 2020 @ 5:04 pm

Looks like you had a lovely trip! I’m in Canada and missing my annual month in Puglia this year. I hope to be back next year. Ciao, Cristina

August 3, 2020 @ 4:42 pm

What a wonderful story of your holiday in Puglia. My partner & I plan on buying a little apartment in Ostuni in the next 12mths. My lifelong dream to live in Italy. Your holiday story has reassured me all the more to fulfill my dream. I’m open to hear any thoughts & ideas about living & buying in Ostuni. So glad I found this website. Thanks again. Deborah (Sydney Australia)