Trekking in Laos: It’s where the Himalayas end and life for the Akha tribe begins

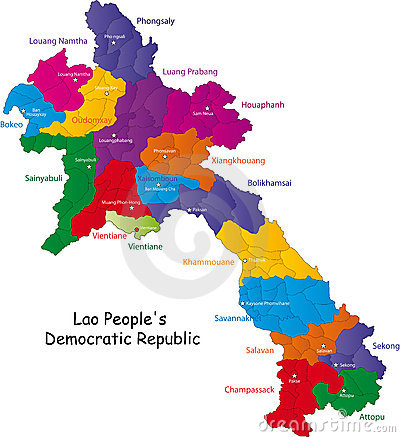

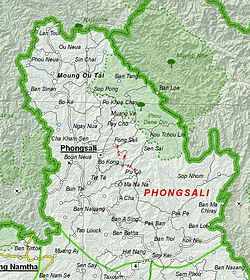

PHONGSALI, Laos — You don’t realize how long a country like Laos is until you go to its northern border. Laos is 1,280 miles long. I went from sweltering along a river in Central Laos to freezing my membranes off in the Lao mountains. I sat in my crude hotel room in this quiet, mountain town of 15,000 about 10 miles from the Chinese border. Phongsali, the capital of the province that juts into southern China, is the jump off point for some of the best trekking in Southeast Asia. It felt like it. I sat on the hard bed in my black turtleneck and khakis, very thankful I brought a stocking cap. I’d need it all the next day when I’d try to stay warm in an Akha family’s bamboo shelter.

This is where Laos’ well-trodden tourist path veers off course. It is an absolute, stomach-turning ordeal to get here. I arrived from a 15-hour bus ride that was right out of the popular book series, “I Should Have Stayed Home.” This would be the “Public Bus Edition.” The bus I picked up in Luang Prabang looked fine from the outside. It was your basic pullman. But as I stepped inside I knew these 15 hours would feel like 15 days. The steps up were filthy. Black grease and dirt caked each step. Half the brown leather seats were broken. It was fortunately only half filled and I slid into one of the broken seats. I could use a seat that reclined almost horizontally. Forget the fact that a crane couldn’t return the seat to its upright position. I needed sleep.

It was 5 p.m.

From Luang Prabang to Phangsali is only about 250 miles. Yes, it took 15 hours. The road zigzagged as if going up one giant mountain. The bus rarely went more than 40 mph and stopped at every hamlet with a noodle shop. It slowly filled to the brim. I offered a mint to the young girl next to me. She took it without a word or smile. I brushed it off as an insolent youth rather than an indirect slap at an American whose military probably bombed her village or killed her grandfather.

Then I saw a young man hand her something else. It was a baby, maybe two or three months old wearing a red stocking cap. He must’ve been her young husband. She started breastfeeding him right next to me. I didn’t take offense to it. What I took offense to was when she adjusted her breasts, the kid kept landing in my lap, his eyes closed, waiting for the next tit.

Meanwhile, after only about five zags, a woman one row behind me and across the aisle started to get carsick. Violently. The driver’s assistant couldn’t get the little blue plastic vomit bags to her in time. One expulsion splattered on the floor, leaving a yellow and white mushy mosaic that started to wreak despite the drop in temperature. I found myself breathing through my mouth. Making matters worse, borrowing a page from FAA regulations requiring “all screaming children to sit within one plane row of John Henderson,” a kid behind the vomitorium started to cry like Pavarotti after he gets his hand slammed by a car door.

And it was only 8 p.m.

I tried to read but there wasn’t a single light when the bus started moving. We were a dark, black bullet heading into the mountains of northern Laos. I looked outside and saw brief snapshots of villages I would never hope to find on a map. What I made out were very crude houses on stilts to protect from flooding. Single bulbs shined from cracks in wooden windows. Rusted bikes and building materials stood outside crude fences or cracked courtyards. No restaurants. No parks. In the morning, chickens livened up the scenery as did tired women hauling water from a single hose into the house. Laos has 49 ethnic groups and I could see some wearing native garb, black skirts or pants with colorful hand-sewn designs. Their faces were wrinkled from age and too many years in the cold.

We were finally disgorged in Phongsali at 9:15 a.m. I joined Pablo, a French-Bolivian I met at the Luang Prabang bus station, to find organized treks through Amazing Tours, one of the top adventure companies in all of Laos. The last time I went trekking in this part of the world, in 1978 not far away in Northern Thailand, I got typhoid and lost 20 pounds in eight days. All I want this time is a good photo for my wall.

It won’t be hard. Here we were at the top of Laos, the bookend of the Himalayas. Not many people come to this part of the world. But Phongsali is definitely worth the trip. It is the provincial capital but a capital in name only. It has one main drag, a dusty two-lane road lined with cheap retail stores, open-air restaurants and government offices. Phongsali borders China’s Yunnan Province and Yunnan architecture is prevalent. The roofs curve upward at the end, a bit like a Chinese temple.

This is also the easternmost point of the Himalayan foothills. This is the end of the Himalayas and you can tell in Phongsali. The town is built on a hill. To get to a bowl of very good noodle soup, Pablo and I had to walk down the steep hill to reach this open-air terrace where a woman stirred a gigantic bowl of steaming noodles with a big pile of freshly cut pork next to it. From the main drag, I could peek through the single and two-story buildings to the valley below. It’s constantly covered in mist, particularly in the heart of Laos’ winter. A pond sits mysteriously at the bottom of the hill. So do the light standards of what looks like a large football stadium over the highway entering town.

I could also tell it’s the Himalayas because it was COLD! My cell phone said it was 56 degrees. Tell that to my frosty nose. As soon as I dropped my bag in my small but tidy room, I put on the nice turtleneck I bought myself in Rome. I dug the stocking cap out from the bottom of my backpack, the same stocking cap I sat in my Rome apartment wondering for 15 minutes if I should take it.

The room at the Viphaphone Hotel was also freezing. The windows are tied together by a little red string, leaving a one-inch crack for the cold air to come in, making indoors and outdoors nearly indistinguishable. But the Western staff is here teaching locals hotel management skills. Between their guidance (the American co-manager rode me around town on her motorbike trying to find a working ATM) and the 80,000 kip (about $10) price, I wouldn’t stay anywhere else.

And the views … oh, I could’ve been in Switzerland with worse fondue. I’d read about the spectacular “endless mountains” of northern Laos. It’s true. They stretch forever, a long, green, forested horizon shadowed in mist. They’re not large craggy, snow-capped peaks you see in mountaineering books. We’re really only about 6,000 feet in elevation. But it was winter here and we were high above the clouds. The mist forms a beautiful blanket below the trees that stretch high around us.

The day started slow but went long into the first night. I joined the same group with Pablo, Jani from Budapest and Yohann and Orianne, a couple from Bordeaux, France. It was a good group: fit, open-minded, well-traveled, funny. Pablo, a professor in Santiago, Chile, was doing research on the effects communist governments have on hill tribes and asked more questions than I did.

It took us forever to get moving. We went to the local bus station where a beat-up bus on its last muffler drove for 45 minutes on a gravel road past hamlets, each one poorer than the next. Houses looked like old Lego structures, just a mishmash of wood planks, propped up by wood poles with a rock base. Boulders were everywhere. Mud paths separated the homes. A Cyclone fence protected the lower end of one house. Roofs consisted of corrugated metal.They looked as if they were built in about 90 minutes. An old woman in a high red knit cap squatted in the mud. Men in ballcaps laughed on the bus.

We stopped at a pretty lake for some decent noodle soup. The lake was formed by one of the six dams the Chinese have built. Our guide from Amazing Tours, Bounhak, or “Boss,” told us the Chinese build the dams but siphon all the electricity to China. After 20 years, they will give the power to Laos at no charge.

“What happens if the dams don’t last 20 years?” Pablo asked.

“We don’t like them much,” Boss said. “We import everything from China, but they’re no good. We make the material here, ship it to China to make products to sell to Laos.”

We all piled into a long motorboat for a 30-minute ride along Lake Nam Ngai. Here, finally, we were away from civilization. We didn’t see a single boat, not one fisherman, the entire trip. The only signs of man were some clear cutting in a rubber plantation on a steep hill. A banana plantation wasn’t far away. It was a lovely trip. The weather was perfect, maybe 70 degrees and the forested hills disappeared in the mist above us.

We passed a small cluster of bright white blowers in full bloom. Poppies. This is where a good opium production started but the hill tribes don’t use opium much anymore. Apparently, lao-lao, Laos’ infamous rice whisky, will do.

The boat stopped at a small, muddy landing where three hard-looking Lao greeted us by pulling the boat up the muddy shore. We donned our packs, tugged at our zippers and started trekking. Up. And up. And up. It was a 1 ½-hour slog straight up at about a 45-degree angle. The hike is described as moderate high to hard. It wasn’t so steep or difficult. We were hiking along a gravel service road. But it was relentless. It never leveled. Occasionally, a motorcyclist would speed down the hill with his back loaded with firewood that stretched nearly the entire width of the road. I had stripped to a sweat-free sport shirt and shorts and the cool breeze felt like an electric fan as I stared down at the incredible valley. The forest-covered mountains led to a valley that stretched all the way to the horizon. The air felt as fresh as a perfume store in Monaco.

Boss pointed to the top of the ridge, seemingly 10 kilometers away and 2,000 feet up. We could barely make out a couple of huts.

“That’s our first village,” he said. “Lunch.”

The village of Chakhampa is about a couple dozen structures scattered around a dirt hill. We were greeted by a whole group of piglets, cuddling and sleeping in the sun. Not far away, another group savaged the teats of their overstuffed mother who was being pushed all over the yard by her hungry offspring.

Chakhampa is just one of 600 villages in Phongsali Province, where 90 percent of the population of 177,000 is rural. Hill tribes primarily live on agriculture, selling rice, corn, cardamon, tea, sugarcane and sometimes rubber trees. There are nearly 6,000 acres of rice paddies in Phongsali Province.

The Akha are one of the 45 ethnic groups in Laos and one of the seven main ones. They are as isolated as any in the world. We were greeted by Akha women who always dress as if National Geographic photographers are going to show up. They wore black leggings with black skirts and heavily embroidered jackets. Their headdresses symbolize their marital status and each is individually designed, sometimes with items such as silver coins, monkey fur or dyed chicken feathers.

Actually, this is how they dress every day. It’s also how they make their lao-lao money, apparently, The women told Pablo they wanted 5,000 kip for a photo.

The village chief, Nouje (pronounced No-ZEE), is 55 years old. He had never been outside the Phongsali Province. That’s almost as bad as never being out of Nebraska. He had a long face under a ballcap at a jaunty angle. He had the slightly round eyes of a Mongol. He looked tired.

Through Boss, Nouje told us a village chief’s tour in office lasts three years and he can hold the title three times for a total of nine years. Hey, there just aren’t enough men to go around in a village of 300 people. Like all people in Laos, he does have complaints with the government. He’s fighting to get water, electricity and a proper school. They use solar power for heat and must bring water up from a well and boil it. During the rainy season in summer, the village turns to mud. People get sick.

He turned to Boss and said, “You’re crazy for coming up here every day.”

And he does. Boss takes trekkers every day of the week. In fact, his girlfriend gave him a raft of heat the day before for working on Valentine’s Day. Boss is 34 and speaks very good English. He went to university for a couple of years and then went to work with hill tribes. He’s only been a guide for seven months but is a Wikipedia of information.

He’s also in damn good shape. He’s about 5-foot-3 but well proportioned with a handsome, round face that makes him look early 20s. He’s a fantastic guide. We’re lucky to have him. So is Laos.

Lunch was eight bowls gathered on a table: chicken, pork, spicy pork, coagulated eggs, two different green vegetables, fish with veggies and chili sauce. I’ve been violently ill three times from eating eggs in Asia and wouldn’t touch the eggs if I was 10 minutes from death. The chicken and pork, however, were fantastic. Grilled on an open flame, they were served in big wide chunks that you could eat with your hands. They could’ve passed as BBQ in any backyard in America.

We continued trekking upward another 2 ½ hours before we descended into another settlement. Peryenxang village also had $50 houses with $1 million views. It consisted of about 8-10 crude wood structures, propped up with boards and covered by bamboo thatched roofs. I wrote my journal in a common area, illuminated by two small solar-powered light bulbs hanging from a long pole.

Another huge feast was prepared: eggs, pickled vegetables, vegetable soup, fish filled with more bones than flesh and pork almost entirely fat. For after-dinner drinks, the village chief brought out a bottle of lao-lao and, like a good host, ate and drank with us. If every night was like this with visitors, I’m surprised the Akha don’t have a top-notch rehab center. Lao-lao can sometimes be lethal if made incorrectly and it’s made in many isolated areas of Laos. The lao-lao in Peryenxang, however, was top notch. It was smooth as silk and chilled from the mountain air.

In between shots, we had an increasingly incoherent conversation with the chief about the life of the Akha. They number 400,000 in Southeast Asia, a potentially solid political force if they ever get electricity. About 80,000 live in Northern Thailand, many of whom bolted Laos during the Civil War in the mid-20th century. The Akha are not Buddhists. They are animists who believe that the being who created earth and life gave Akha the “Akha Zang” (Akha Way), their guidelines for life. They believe that spirits and people were born of the same mother and lived together until a quarrel led to their separation. That led to the spirits going into the forest and people remaining in the villages. Since then, Akha believe that the spirits have caused illness and other unwelcome disruptions of human life.

Spirits, however, did not disrupt my morning. At precisely 3:45 a.m., every rooster started cock-a-doodle-doing. Not one. Not two. All of them. It’s like they all organized the night before and said, let’s screw with the trekkers who stayed up until 10 p.m. drinking lao-lao. Then came the women working in the kitchen. Boiling water. Pounding cotton. Bashing pans. Then the babies woke up, crying. All of them. Between the roosters, women and babies, it was like Grand Central Station with better views.

For breakfast we had something called Khaojepapa, a coagulated sticky rice mix with sweet sauce. It tastes like sweetened glue. After three small bites, I joined the group as we visited a one-room schoolhouse then made our way back to the boat, retracing our steps in brilliant sunshine. We passed back through Chakhampa. We saw a lot of men sitting on their haunches, like baseball catchers, without a lot to do but chat. They seemed oblivious to the gorgeous view right off an Oriental tapestry around them. I was mesmerized. For two days of trekking, putting up with a vomit-stained local bus for 15 hours was worth it.

This isn’t Colorado. This isn’t the Alps. This is more. The paths of Northern Laos are definitely worth beating.

June 1, 2017 @ 1:28 am

Fabulous region and a story well told! Thank you! Offbeat destinations have a certain lure.

June 1, 2017 @ 5:07 am

Thanks for the note! I’m hoping the Akha don’t get running water and toilets. Then they’d be overrun. They seem happy. They wouldn’t be with bus loads coming in.

January 19, 2018 @ 3:10 am

Thanks for your writing back. Tell you what, I was once doing frequent trips (as part of an international mission to provide utilities) to the region you wrote about. I have to agree with you – they do seem happy. And since then, I have turned into a travel writer : ) Speaking of offbeat destinations, if you do not mind me leaving a link, since you enjoyed Laos, you might want to consider North East India for your upcoming travels. There’s more info at https://www.backpackingseries.com. Happy journeys in 2018!

January 17, 2018 @ 3:31 pm

Next week I return to Lao for my 21st time in 6 years. I have a business that develops UXO survey electronics. This time I return with 9 other Americans to attend a handover ceremony for an elementary school we funded in Vieng Xai, Vang Vien District for 263 kids. January 29 will be the first day of classes. I’m lucky to haveI had this opportunity to help.

January 18, 2018 @ 12:03 am

Thanks for the note, Ken. Any off-the-beaten path places in Laos you recommend for my next trip?

January 18, 2018 @ 9:30 am

The people in the mountains of Attapu touched my heart and reason. Legend there is that on a few bombing missions, Air America ordnance tech(s) compromised the fuses on many bombs so they would not detonate in the villages. We are talking about big bombs (Mark 81s, 82s and 83s). Thatâs a range of 250-1000 pound bombs.

Where are you out of?

Ken Hayes

President

Aqua Survey, Inc.

908-347-4144 M

908-788-8700 W

January 19, 2018 @ 12:38 am

Ken: Interesting anecdote about Air America. I had no idea. I live in Rome after 23 years in Denver. I grew up in Oregon.

October 9, 2017 @ 3:26 pm

Hi! I’d love to know more about the tour company you used. Is Amazing Tours based in Laos? Do you have their website or contact information? Great article!

October 9, 2017 @ 3:27 pm

Hi! I’d love to do a trip just like this in November. Could you tell me more about the guide/tour company you used to make arrangements? Any info to help me plan would be awesome…:) Thanks so much for the great article!!

October 10, 2017 @ 12:09 am

I used Amazing Lao Travel. It’s the main travel company in Phongsali. There’s another down the hill run by the government but Amazing Lao has more varied trips. No need to make reservations in November. I went in high season and just walked in and arranged a trip. The more people you have the cheaper it is but they’ll sit down with you and ask how many days you want to go and where. Then they’ll put you with a group with similar interests. The office is right on the main drag not far from the bus stop. The website is http://www.explorephongsalylaos.com. The phone number is 088-210-594 (not including country code of 856.

If you have any other questions, be sure to write. Good luck.

John Henderson

October 10, 2017 @ 12:14 am

Thanks for the comment, Megan. As I just wrote another reader, Megantom (you probably know him/her), Amazing Lao is at http://www.explorephongsalylaos.com and 088-210-594. Add country code 856 if calling from outside Laos. The office is located right down the hill on the main drag not far from the bus stop. No need to make reservations, I don’t think. I went in high season and had no problem getting a trip organized. This part of Laos is off the beaten path. It gets some publicity but it’s hard to reach. That 15-hour overnight public bus ride is rough. We saw no other hikers on our two-day trip.

If you have any other questions, feel free to write again.

John Henderson

November 7, 2018 @ 6:04 pm

Wow! I love how you describe your trip! I’ve never been to Laos yet, but because of how you write your adventure, I’d consider trekking here should I get the chance. Does Amazing Tours have a website or other contact details?

November 8, 2018 @ 9:16 am

Thanks for the kind note, Rhema. Amazing’s website is http://www.explorephongsalylaos.com. I walked right in and joined a tour the next day. I never had a reservation. Check with them and see if one is recommended during the month you’re going. They’re good at replying to emails.

November 8, 2018 @ 9:59 pm

That sounds great, John! Would take note of that once I get on my backpacker mode on again. Thanks again and keep on sharing your adventures! 😀

January 18, 2023 @ 7:03 pm

What do you have against Nebraska my home state?? lol. Amazing adventure.. thanks for taking us there as we never leave the state.