Uzbekistan: Following in the footsteps of Marco Polo as the world discovers the old Silk Road

(Last of a four-part series on my three-week journey through Central Asia)

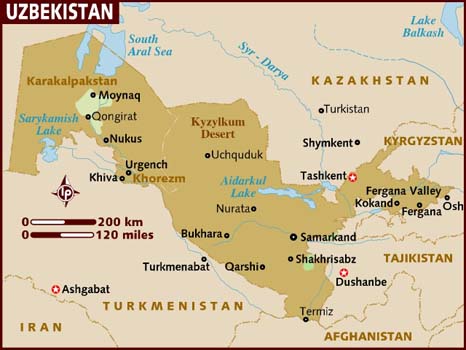

TASHKENT, Uzbekistan — The Silk Road stretched from eastern China to what is now western Turkey, a 4,000-mile highway of transported goods that connected East with West like no time ever before. It was the 2nd century’s version of Amazon.com. Genghis Khan did his best to destroy it; Marco Polo did his best to revive it.

Sitting in the middle of the old Silk Road, like a hub of a subway network, is Uzbekistan. No place in Central Asia do the riches and glory of the Silk Road’s commercialization come through more than here. Giant mosques look like museums. Mausoleums could pass for summer homes. Gardens and pools and castles dot cities like ancient country clubs. From the 6th to the 12th century, Uzbekistan was the place to go if you were a trader, traveler or dreamer.

Today, it is a country in positive transition. A new president has softened its rough edges and the food and architecture are from another world. The New York Times listed it as one of its places to visit in 2019.

Today, it is a country in positive transition. A new president has softened its rough edges and the food and architecture are from another world. The New York Times listed it as one of its places to visit in 2019.

I’ve done many overland border crossings alone. Kenya-Tanzania. Thailand-Malaysia. Brazil-Uruguay. I never had a problem. I’d read Uzbekistan was manic about forms, kind of like the USSR in the ‘60s. Strict registration rules made you collect forms from every hotel you stay at and every money transaction you make. A homestay required a visit to a local office of Visas & Registration. I expected I’d be tied up at the border filling out documents and giving itineraries.

However, I also read that Shavkat Mirziyoyev, the president elected in 2016 to replace the old communist hand, Islam Karimov, had loosened restrictions to increase tourism. As a U.S. citizen, I didn’t even need a visa.

Mirzioyoyev’s gentler hand was in evidence when I broached the 100 yards between the Tajik and Uzbek border patrol buildings. I approached the Uzbek building with “O’ZBEKISTON REPUBLIKASI” sign and a beaming Uzbek soldier said, “Welcome to Uzbekistan!” I’ve never had a border patrol soldier even smile at me before.

I walked in alone. No one else followed me. This was not Tijuana-San Diego. I showed my passport and visa and was out the door in five minutes. No form to fill out, no money to declare. I was free.

Then I wasn’t.

About 20 cab drivers descended on me. I said, “Samarkand” and they all shouted “FIVE DOLLAR!” “FIVE DOLLAR!” A young man in a clean white dress shirt cut me out of the crowd and led me to a parking lot. I agreed to $5 or 50,000 som. When I reached his car, a burly man started yelling at me. “HE NO TAXI! HE NO TAXI! I OFFICIAL TAXI!” He showed me his car. A sign read “TURIST TAXI.” Whether it was real or not, it looked more official than this guy’s sedan. I got in the older man’s back seat and the young guy sat in the front trying to get me to leave, speaking in Tajik, which is spoken in southern Uzbekistan, as if I’d hear something to convince me. The older guy came, pulled him away and pushed him. The young man laughed. They acted as if they were old friends.

The old guy got in and we started to leave. About five minutes from the border, he pointed at his empty front seat.

“FIFTY!” he said. He pointed at me.

“FIFTY!” He then said “SAD!” No, he wasn’t unhappy. “Sad” is the Tajik word for 100. I was unhappy.

“ONE HUNDRED?!” I said. “No!” I motioned to go back. He stopped the cab. He made it clear I’d have to pay for the empty seat. Since I waited 15 minutes for him to find another passenger and at the time thought of paying extra to leave without one, I agreed. My anger subsided when I forgot I was in the middle of a desert and put it in perspective. I was paying 100,000 som (about $10) for nearly an hour cab ride.

Here’s a look at my week in Uzbekistan one step at a time:

SAMARKAND. I once had a list of the top man-made structures I’ve seen. I always had the Taj Mahal, the Eiffel Tower, St. Peter’s and the Colosseum. In Samarkand I added a fifth.

Registan.

I’d never heard of it until I planned this trip. In fact, I didn’t think much about it during my first two weeks. But when I left my lovely hotel here and walked down the street, Registan stopped me in my tracks, like when the Taj Mahal emerges through the streets of Agra. Registan is three massive mosques on three sides of an enormous square. Two nearly identical mosques face each other with the third, slightly smaller, in the middle. Busy Registon ko’chasi street is lined with photographers. I returned at night and the scene had changed. The mosques exploded in blue and yellow. The blue onion dome, built by the Russians in the 19th century after an earthquake, looked like a flying saucer.

I just stood there, my mouth agape. I caught myself saying, “Fuck!” “Holy shit!” “Mother of God!” After 105 countries, it takes a lot for me to mutter “Mother of God.”

Samarkand and Burkhara were the halfway points for many traders from Baghdad and Aleppo in the south to meet traders from Kasgar and Yarkand in the north. A number of rabat or caravan lodgings were set up along the route and with lots of horses and camels to trade here, this area became real wealthy.

The Sogdians, an Iranian civilization that ruled this area in the from the 6th to 11th century, used the money to dress up their cities. Samerkand got a good share of the booty as my visit proved this place was one of the wealthier areas in the Muslim world in the 13th century.

Registan’s three mosques are eye popping. The Sher Don Medress has a gorgeous portal of lions (they’re supposed to be tigers) chasing deer. The architect, Shaybanid Emir Yalngtsh, put these strange, large eyes on the lions’ backs to signify Islam’s law against depicting animals.

The middle mosque, Tili-Kari, has an optical illusion inside. The ceiling, covered in gorgeous, bright gold leaf representing Samarkand’s wealth, looks like a dome. However, because the leaves get smaller as they reach the center, it’s actually a flat ceiling.

The left mosque, Ulugbek, is the most original. It took only three years to build and inside were classrooms where such subjects as astronomy, math and theology were taught.

The most interesting story behind a mosque was about 300 meters northeast of Registan. The Bibi-Khanym Mosque isn’t all that beautiful. It’s more known for being one of Islam’s tallest mosques with a dome 41 meters high. It collapsed in an 1897 earthquake and refurbished in the 1970s and also during independence in the ‘90s. But today it’s more known for its legend.

Timur was a 14th century Pesian conqueror who ruled much of this area during the Persian Empire. He had a Chinese wife named Bibi-Khanym. She had the mosque built to surprise him when he came home from raping and pillaging. However, the architect fell in love with her and refused to finish the job unless she kissed him. Then Timur found out.

Oh-oh!

He executed the architect and ordered all women must wear veils entering the mosque so as not to tempt other men. Women adhere to that still today.

My hotel, Jahongir B&B, is a real oasis with a great buffet. It’s a series of rooms wrapped around a big garden-like courtyard. The manager, a tall handsome Uzbek, lived in Fort Myers, Florida, for six years and had an American sense of humor.

“I lived in Florida — unfortunately,” he said.

I had my first good meal in many days. Uzbek food is fantastic, the queen of Central Asian cuisine. Entire menu pages are devoted to healthy, fresh salads that became my daily appetizer. The kabobs sizzle in beautiful displays and the plov, Central Asia’s rice pilaf with a big pile of rice, lots of veggies, garbanzo beans and usually meat, is nowhere better than it is in Uzbekistan.

I took Lonely Planet’s recommendation and went to Besh Chinor, a modest local diner with a pretty indoor courtyard. On a perfect 70-degree night, the waitress brought two massive trays of sample salads. I chose the tomato-green onion-yogurt and the pickled cucumbers. Then came two long sizzling chicken kabobs, so tender I cut them with a fork. That and a big Pulsar local beer, the total bill was 37,400 som, about $4.

I took my hotel’s advice and went for the best plov in town. It was a place oddly named Plov Sentr. The cab driver picked up two other passengers and we drove to the north end of town, far away from any tourists or even any Roman-letter signage. We passed smart, obviously modernized government buildings and streets lined with cheap retail stores.

After about 40 minutes he finally stopped on a narrow street in front of an open-air shop with a sign in cyrillic. I saw some cooking equipment inside. I showed a man standing at the door the note. He nodded.

This is the place.

Plov Sentr is a classic Uzbek businessman’s lunch place. I sat down under a fan to chase away the 90-degree heat and a woman immediately brought out a steaming pile of plov and a salad with sour cream dressing and a big, doughy chunk of Uzbek bread. The plov was great, clean, fresh, hot. The walls had paintings of everything from waterfalls to giraffes and deer by a lake.

Fat and happy, I took another cab to Shahi-Zinda, still considered one of the most beautiful places in Islam. It’s a long corridor of mausoleums. It’s the prettiest place of death I’ve ever seen. Many of the mausoleums have unnamed people in tombs that sit in the middle of the floor like furniture. The most beautiful, filled with bright tile work, is of Shodi Mulk Oko, built in 1372 and home to the sister and niece of Timur. One of the tombs allegedly holds Qusam Ibn-Abbas who was said to have brought Islam to this area in the 7th century.

The tilework is exquisite. It’s all bright blue as if painted yesterday. In fact, most of it nearly was. The oldest date to the 14th and 15th centuries but much of it was restored in 2005. Still, the colors exploded in the heavy sun.

BUKHARA. This is Central Asia’s holiest city, once part of the axis of the old Silk Road although a bit later than Samarkand. I could see the middlemen during these 300 years of dealing made a damn fortune. Both cities have enduring landmarks that are spectacular. Samarkand looks like a iman’s wet dream, full of giant mosques and gorgeous mausoleums.

Bukhara is more subtle. The center of Bukhara is Lyabi-Hauz. Bukhara thrived in the 16th century, after getting poleaxed by Genghis Khan in 1220 (after he did the same to Samarkand) and Samarkand’s Timur in 1370. For 400 years, 200 stone pools called hauz watered the city. They were also used by the people to bathe and socialize. They were like the old Roman baths but 1,500 years earlier the Romans had the good taste, not to mention hygiene, of changing the water. In Bukhara they didn’t.

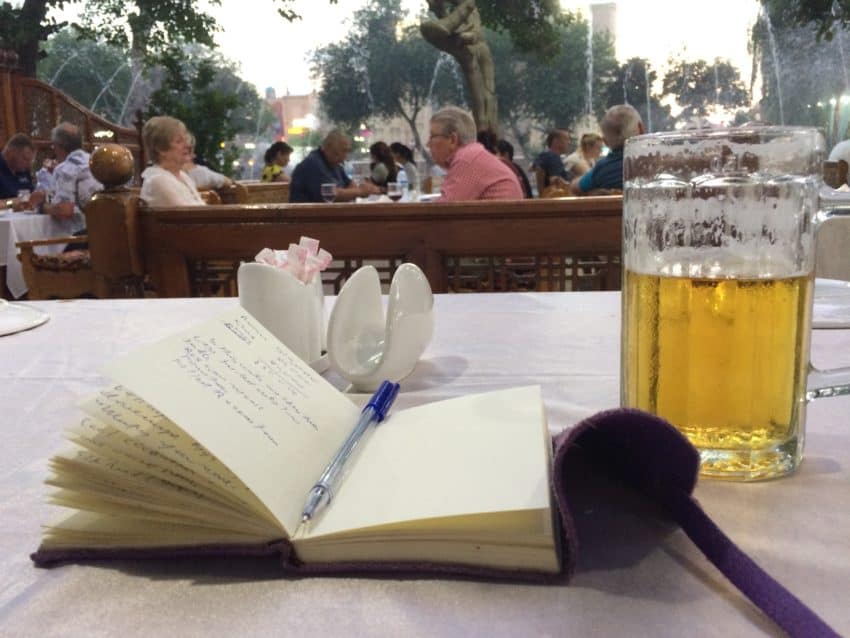

Thus, the average life expectancy of a local was 32. The only big hauz that has survived is Lyabi-Hauz, in the heart of the city next to the main drag. It’s a big square Olympic-sized pool surrounded by tables, shady trees, bars and ice cream stands. Tourists sit around drinking cold draft beer and watching ducks float around.

I wanted to avoid it. It looked like a tourist trap but then, nothing in Uzbekistan is real expensive, not even tourist traps. Tired, hot and thirsty from a short walk, I asked how much a beer was: 20,000. About 2 euros.

I love Uzbekistan.

I sat down under a tree and drank a big bottle of Sarbast, one of the best beers I’ve had in Central Asia. I had a group of women take my photo with the pool in the background. The four middle-aged ladies were part of the Italian group. They were 40 of them from Northern Italy all cruising around Uzbekistan for a week on a tour bus. We tortured each other with what Italian food we missed. (I would’ve killed for a gorgonzola and sausage pizza at my C’era Una Volta pizzeria) and for a good glass of wine.

My Arabon Hotel is a pleasant, simple two-story hotel where I wrote in the courtyard, listening to birds chirp in the large vines coming down from the second floor. It’s in the middle of Old Town, a warren of narrow alleys that haven’t changed in thousands of years. But it’s changing soon. The whole neighborhood is under construction. Rubble has joined the dust on the streets. Construction workers were everywhere. I had to take detours around scaffolding to get to the Lyabi-Hauz. It’s always a good sign when a city has enough money for construction, but I don’t think Rudaki, the great Central Asian poet who lived here for years, had to listen to pounding hammers while he pounded out poems.

The food continues to lift Uzbekistan up from its Central Asian neighbors. I took the advice of the hotel manager and went to Chinar Chaikhana, a two-story open-air restaurant specializing in Uzbek cuisine. It’s remarkably casual. I entered and asked the manager if they had plov. He yelled to the kitchen, in Tajik, “Do we have plov now?”

An indecipherable comment returned.

“We have plov.”

I hadn’t even sat down yet. I ordered plov and a Russian beer then read in Lonely Planet that its kabobs are the best in town. I leaned over the staircase and said, “Excuse me! Can I change my order to a meat and chicken kabob?”

He ran back to the kitchen. The kabobs were fantastic, sizzling and fresh and tender. The beer was ice cold and the breeze through the open air terrace cooled my sweating body.

At night, Bukhara is famous for … nothing. I stopped by a modern bar called Ecko Bar. Small, dark with a hip vibe, it has a big screen and a bar filled with spirits. They said they’d have the Chelsea-Arsenal Europa League title game at midnight. When I returned at 11:30 p.m., four guys sat around a table drinking Coke and fruit juice. One young guy smoked a hookah. The guy who confirmed the game said, “We’re sorry. The TV doesn’t work. No game.”

“OK,” I said walking to the bar. “I’ll take a beer. You have Sarbast?”

“No beer. Ramadan. You can go to the grocery store and buy some and take it to Lyabi-Hauz.”

I went home through the pitch black alleys of the old town, the pounding hammers long gone silent.

The next morning I explored Bukhara under overcast skies and was as impressed as Genghis Khan was. He took one look at the 47-meter tall Kalon Minaret (1172) and let it stand. Maybe it reminded him of his penis. But even more impressive than its size is its design. Each panel is individually carved. It stands between two facing mosques, Kalon Mosque, which replaced the one Genghis leveled, and the Mir-i-Arab Medressa, with blue domes you can see from all over.

I ventured farther afield to the Ark. It’s a castle inhabited from the 5th century to 1920. I walked through the ceremonial grounds where they honor the old Bukhara emirs, saw the apartments where visiting heads of state stayed — not too far, not coincidentally, from the mint and harem. I saw portraits. The area where the stables were is still an open area with the remains of three horse-drawn carts parked along the edge.

Speaking of which I went to the Zindon (Tajik for “prison”) where a British military officer named Charles Stoddart spent three years for the audacious offense of not bearing gifts or a letter from Queen Victoria when he visited. He spent much of his time in the Bug Pit, a 6 1/2-meter pit with a cage over it and only accessible by rope. He spent it down there with lice, scorpions and other disgusting creatures. In the pit today is a dummy sitting on a dirt lump with various som notes scattered around from morbid tourists. Another British soldier, Arthur Connolly, came trying to appease the emir and release his buddy. It did not go well. They were both beheaded in front of the Ark.

For dinner I succumbed to the tourist trail and went to Lyabi-Hauz, a restaurant that wraps its way around the Lyabi-Haus pool. I sat uncomfortably on a low-slung table meant for sitting Indian style and stared at the packed restaurant filled with Russian tourists. It really was a lovely night, though, with the sun setting and water glistening. Russian love songs played while I ate some fantastic plov with black grapes and a fitness salad.

As I finished my beer, an old man, stooped and looking ready to die, walked slowly, with his head down and sat awkwardly on the bench opposite me. My waiter brought him some leavened bread and put his hand on it to show where it was.

He was blind.

The waiter later brought a bowl and poured in some meaty soup for him. A nice touch in a city known for so much violence.

KHIVA. I had a fleeting tour of Khiva. Too bad. It’s the first time I’ve ever stayed in the middle of a perfectly preserved medieval city. Khiva was a mere fort along the old Spice Road before the Khorezm Empire in this northwest part of Uzbekistan grew from the 10th to the 14th century when the capital was moved from Old Urgench in what is now Turkmenistan to Khiva.

The Khorezm built a massive walled city called Ichon-Qala filled with sandstone structures connected by dusty streets. Ichon-Qala remains to this day, almost identical. The taxi from Urgench after a long, six-hour taxi ride from Bukhara, drove through what looked like a castle gate, complete with ramparts. We stopped at my B&B, the Mirzoboshi, which has a big, open-air teahouse and a building of simple single rooms behind it.

I dropped my bags and looked around. All around me were towering minarets and blue-domed mosques. It was like an Islamic theme park. The Uzbek government had long ago banned the call to prayer. What a shame. To hear a mosque blaring out an iman’s voice in the air filled with towering Islamic architecture would be a cultural orgasm.

I was beat after bouncing along a lousy Uzbek highway for six hours. I sat down with the owner, a husky, round-faced Russian man named Makhnud Baltaev. I told him how much I loved Uzbekistan, the food, the people, the freedom. It wasn’t nearly the police state I read about. He said the fall election and getting Mirziyoyev as the new president after the old commie hand died helped a lot.

“It’s changed 30-40 percent,” he said as he dug into an impressive pile of plov. “Before you couldn’t say anything. Now the president has a website where you can write complaints. If he can help, he does.”

Baltaev, however, wouldn’t bad mouth Karimov, the predecessor. When you’re sitting in the sun, sipping cold beer and looking at mountains or minarets, you forget you’re bordering on some major war zones. Afghanistan borders Tajikistan; Iran borders Uzbekistan. Turkmenistan, a short drive from Khavi, is no Cancun, either.

“Central Asia has a big problem with ISIS,” he said. “He really kept the border safe.”

Khiva is called the Museum City and no city is more appropriately named. The old buildings, from the medrasses to the mosques, have been turned into museums. A map showed 52. I first went into its Ark. The castle has two beautiful mosques with spectacular blue tile still glistening on a cloudy day. Out front is an open courtyard where they performed executions. The adjacent jail was closed but I can imagine what it was like being on death row and hearing an ax chop off a head outside.

“NEXT!”

The beauty of Khiva is astounding. Everywhere I turned a bright blue dome towered above me. The two giant minarets serve as twin peaks holding the city together.

I walked 10 minutes along the Ark’s big West Wall to the North Wall. I walked back toward the West Wall where Khiva’s fascinating skyline got closer. By the time I got to the middle of the West Wall, two mosques and a minaret were right in my picture frame. The sun had dipped from under a cloud and bathed the monuments in brilliant sunlight.

Satisfied with my photos, I started walking back. But about 50 yards away, I had my, literally, Kodak moment. A couple had climbed to the roof of their hotel. They were sipping beer, staring off at the same view as I did. I got behind them and shot the couple staring out at a bright blue mosque and mausoleum.

A lover’s view set forever in a timeless city.

TASHKENT. I polished off my Central Asian adventure by polishing off two bottles of wine and three beers in Uzbekistan’s lovely capital. It was a good way to end an otherwise exasperating last day. When I woke up in Khiva the day before, I had no cash. None. And I needed about 80,000 som to get to the airport.

I wolfed down a breakfast of cheese and bread. I had 15 minutes to get cash before the taxi left. Every cash machine I tried kicked back the same message, in English: “Your bank has no response.”

I raced back to the B&B, using the minaret as my compass. The driver was there with the assistant manager. I told him my dilemma. I suggested Makhnud pay him later and I’d send him money through PayPal. PayPal? I might as well have said use money from Mars.

The assistant manager said, “Don’t worry. He’ll take you for nothing.”

I was too grateful and desperate to argue. I just blurted out a promise to save his life whenever he needed and hopped in the car.

When I arrived in Tashkent, my driver was a husky 40ish man with some decent English hired by my B&B, also called Jahongir. I asked if a cash machine was near the hotel. He mentioned one. Knowing my card was on a bad run of luck I suggested he stop on the way. Thus began a city tour not found in guide books.

We stopped at a luxury hotel. No. It was out of money. I went to a long row of bank machines. Nope. They wouldn’t take my Visa debit card. Another bank machine would only dispense dollars and would give nothing less than $100, way too much for one night in Uzbekistan. Finally, at the sixth stop, a machine allowed me to change the dollar amount. I got $40 U.S. and was set for the day.

I checked into my B&B and had a horrible welcome wagon. Not only was my room barely big enough for a bed and a backpack but they wouldn’t accept Visa. It cost $25 plus $10 for the two airport shuttles. I needed $5 more dollars in som.

So instead of going to one of Tashkent’s famous museums or visiting its beautiful Russian orthodox church with the gold onion domes, I went on a mad dash around its highly disappointing Old Town looking for money.

I was desperate. I thought I’d be stuck in my room dining on my three remaining Clif Bars. A woman in another bank suggested KapitolBank, whose machines had mocked me from Khiva to Tashkent.

It was 3 p.m. and broiling. I still had on jeans and my black cotton India long-sleeve shirt that was plastered to my body with sweat. One of the many nice Uzbeks I met told me to cross the street and walk. It was on the right.

I tried the cash machine and left before it even declined me. I went to the bank teller. I tried not to clench my fists. While I talked to her a short man in a position of authority took me outside.

“You’re using the wrong machine,” he said. “Let me show you.”

We went around the side to an identical machine. I put in my debit card, punched in my numbers and — wah-LA! — out came

400,000 som.

At Alfarso, I had a lovely meal of chuchvara (dumpling soup) and fried pelmeni (meat-filled pockets) sitting outside on a perfect evening on a busy Tashkent street. I then went next door to The Irish Pub where I met an Uzbek journalist for the Champions League title match.

Bach Hoosier is a husky, bespectacled journalist who has written under communist and democratic regimes. He had articles “prohibited” before but still has an interesting outlook about working here from a journalist’s perspective.

“When my younger colleagues ask me, ‘What about press freedoms?’ nobody tells you, Do not write this,” Hoosier said. “You have freedom in your heart. Open your mind. If you have balls, you can write whatever you want.”

We drank beer and talked politics as Liverpool kicked the daylights out of Tottenham Hotspurs on a big screen in front of us. It was the last night of a momentous three weeks in an underappreciated part of the world. Fantastic mountains. Great food. Incredible history. Lovely people. Two millenniums after this region started its transcontinental, cross-cultural shopping bazaar, one thing became very clear to me.

The Silk Road will never die.

June 28, 2019 @ 3:16 pm

Fascinating post. Sounds like a really unique place which we are so interested in visiting. Interesting to read so much about your trip. Really good.