Vang Vieng: Laos’ one-time party center no longer “Death in Paradise,” thanks to crackdown

VANG VIENG, Laos — I’m writing this at my hotel dining room table looking down at boatmen readying their long, narrow boats to ferry travelers up and down the tranquil Nam Song. Across the peaceful river, seemingly as close as a short par 3, are the towering karsts, huge mountains with sheer sides and jagged peaks that have adorned Oriental tapestries since the Ming Dynasty. It’s a scene that has been featured in museums from Jakarta to Tokyo, on collectors’ walls from San Diego to Moscow. Watching it in the cool early morning mist of a Lao winter day last month, I felt as if I was drifting away on a soft current, butterflies shepherding my bow.

Yet this river, as recently as six years ago, was one of the most deadly sites in Southeast Asia.

In 2011, Vang Vieng’s small hospital recorded 27 deaths in the river. This does not include unreported deaths or people dying after getting emergency transported to Vientiane, the capital. Keep in mind, the Nam Song is not the Colorado. It has no rapids. The Nam Song (“song” means “river” in Lao) is as peaceful as a Swiss summer. The only white water ever found on the river was the beer foam that splayed a one-kilometer swath from all the bars that lined the banks.

It all started with the inner tube, a symbol of leisure akin to a hammock or lanais chair. In the 1990s, adventurous backpackers seeing a path less beaten started trickling into Laos, a tourism backwater ever since the communists ended a 650-year-old monarchy in 1975. In 1998, a 60ish Vang Vieng native named Thanongsi Sorangkoun bought some inner tubes for the travelers who stayed in his guesthouse to volunteer on his 30 acres of mulberry trees and in his vegetable garden.

Word got out.

Soon, backpackers with a thirst of adventure — and, especially, booze — poured into Vang Vieng to float down the Nam Song. The local Lao, still struggling after 20 years of communist rule, cashed in. They tapped into the Westerners with loose wallets and damaged kidneys and opened bars along the river. More than a dozen lined a stretch no more than a kilometer long. Combine cheap beer (a bottle of Beerlao, Laos’ national beer and, well, ONLY beer is about 8,000 kip or about $1) with a river, regardless of its current, and you’ve got problems. Then mix in Lao-Lao, Laos’ brutally strong but surprisingly smooth whisky made even smoother when sold in buckets of ice which tourists mix with Coke and Red Bull.

Then add rope swings along unsurveyed river banks and you’ve got deaths. In early 2012, an Australian man cracked his skull on a rock and died after leaping from a rope in water too shallow to even float, let alone jump. Soon, a hastily written sign was posted near the swing reading, “Do Not Jump or You Will Die.” People tried swimming from bar to bar without an inner tube and drowned.

“I thought I would it would be a cheap and ecological way to see the river,” Sorangkoun told The Guardian newspaper of London. “I accidentally started the whole thing.”

In 2012, the Lao government tired of the Australian and British embassies asking pointed questions about why their citizens were dying in this small town in central Laos. It didn’t help when a TV crew from the Australian news program “60 Minutes” arrived for a documentary eventually entitled, “Death in Paradise.”

Soon, Vientiane police and even Laos’ president stormed in and did what communist governments are really good at. They suppressed free enterprise. They closed down all the unlicensed bars as fast as they could open a beer bottle.

Last month, five years after the crackdown, I walked down Vang Vieng’s dusty, narrow main drag. The town of about 30,000 had a sleepy quality to it although it’s clear tourism still fuels the locals. The streets were lined with adventure companies hawking trips with giant photos of screaming Japanese hanging onto a zipline or a mob of big white guys pulling their inner tubes through a cave.

Where there wasn’t an adventure company stood a hostel or a guesthouse or a restaurant advertising cheeseburgers and Western breakfasts. One place even specialized in fried chicken. I passed one hostel where backpackers filled an open-air lobby showing an old episode of “Cheers.”

On another main road near the abandoned airfield, I met up with Neil Farmiloe, a New Zealander who runs Pan’s Place, a hip, quiet guesthouse with an open-air courtyard in the back and pretty good pizza. He tired of New Zealand’s weather and came to Vang Vieng 11 years ago, at about the time when inner tubing began to explode. At one point, backpackers outnumbered locals here, 15-1.

Over tall bottles of Beerlao, I sat with Farmiloe in his open-air lobby and heard about the bad old days.

“If you were 20 years old, it was like paradise,” Farmiloe said. “It just got over the top with the number of people dying. The local Lao weren’t very impressed, either: people drunk wandering through town in their bikinis and shorts being sick all over the place. Now we still have people going tubing but there are no swings and stuff. There’s no place dangerous.”

The rural Lao are animists. They believe in spirits and firmly feel evil spirits live in the Nam Song after that era of death. You rarely see a Lao older than a boy on the river except for fishermen.

The crackdown hurt the economy only for a short time. Gone were the cheap backpackers. Coming were the middle-aged, better-heeled tourists who want to stare at the karsts while dining on Laos’ excellent French-influenced cuisine. Meanwhile, Vang Vieng kept its adventure chops by emphasizing ziplining, kayaking, caving and rock climbing.

The Nam Song is still around.

“I (recently) kayaked down,” Farmiloe said. “It was amazing. It was so nice and quiet. You could suddenly hear the river. Before that all you’d hear is loud music. It’s a lovely place now.”

I can vouch for that. I’ve kayaked rivers in Belize and oceans in New Zealand and California and nothing matched the tranquility of paddling down a river in rural Laos. I stepped into one of the larger adventure companies where some bored Lao perked up behind desks when I asked about a couple days of adventure. Caving. Kayaking. Ziplining.

I joined four Norwegians and three South Koreans for a somewhat riotous trip through a cave on inner tubes. We pulled ourselves through using an elaborate network of ropes that stretched 100 meters into a cave then turned around and returned. About three other groups were inside, all with headlamps which lit up the inside of the cave like Olympic Stadium. The screams of Koreans getting splashed by their guides made the cave feel like a cheap Asian horror movie.

The kayaks were a nice elixir. Kayaking the Nam Song is like a leisurely stroll through a park. It’s low water season, meaning the Nam Song moves at the pace of a swan. The kayaks are long, wide, yellow plastic boats with two seats and foot rests. Back support is limited and I found myself lying prone as if watching TV on a couch. I had no problem paddling.

The scenery is of an Oriental tapestry. On a brilliantly blue day in the low 80s, the krasts towered over us to our right, On the other side was quiet village life. A fisherman in a conical hat and pole over his shoulder walked along a path under a palm tree. Fishermen in T-shirts holding nets dove in the shallow river. We passed under little bridges. Butterflies fluttered over our paddles. Except for the growing tension in my biceps, it was the most peaceful time of my four weeks in Asia.

We also saw the remains of this river’s deadly past. Along the river are numerous crude wooden platforms built in trees. This is where many rope swings hung. This is also where many travelers met their deaths, swinging out of trees, tanked to the gills, and hitting their heads on hidden rocks or just failing to respect the current. We also passed areas where an entire series of tables and chairs were left vacant, the remnants of a party long gone quiet. These were some of the unlicensed rave bars the government closed in 2012.

Only a couple bars remain. They looked lonely. I saw three bearded men in their 20s pour themselves onto their inner tubes, hooting and hollering although there was hardly anyone else around to hear it. We stopped at another. Estelle’s “American Boy” played on the loudspeaker as we climbed the steps. I had Beerlao for 15,000 kip ($1.80). The Koreans crashed in hammocks, another couple appeared to sleep on a table. I stood over the river and photographed kayakers — sober kayakers — paddling along with smiles. My God, I thought, did I look this peaceful? Not one inner tuber floated by.

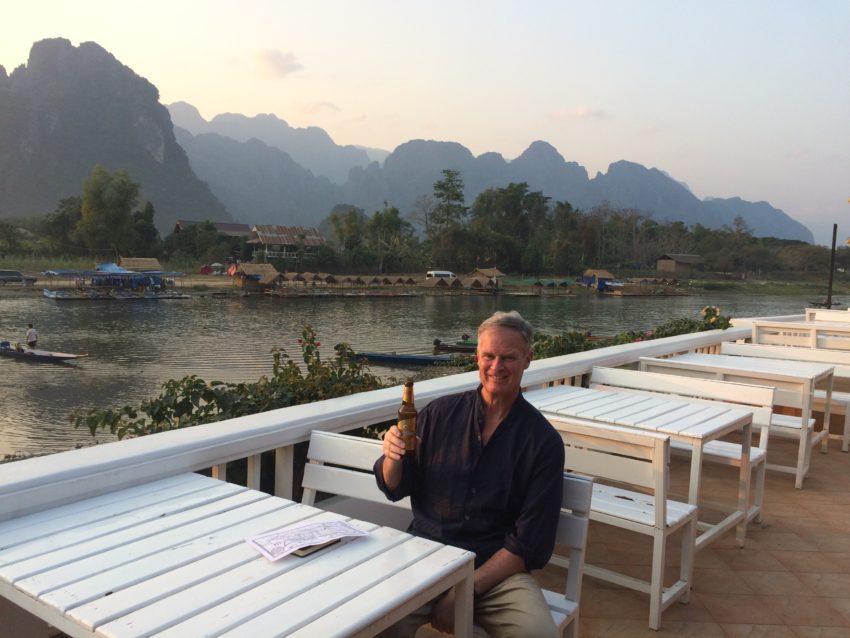

We traveled about five kilometers over about two hours, a nice little workout in brilliant weather. We docked right below my hotel where I sat on my sun-splashed deck and had a Beerlao.

One.

March 23, 2017 @ 9:41 pm

Love, love, love Laos. Great blog entry.