Walk across Rome without traffic: A stroll across a 3,000-year-old city

Living in Rome is like living in a big city with a small town right across the street.

Can’t believe you can get a small-town feel from a city of 2.8 million people who drive like they’re escaping a coming earthquake? Just walk down a street. In fact, walk down many of them. Walk down them all day. Chances are you’ll discover my favorite Italian word: tranquillo.

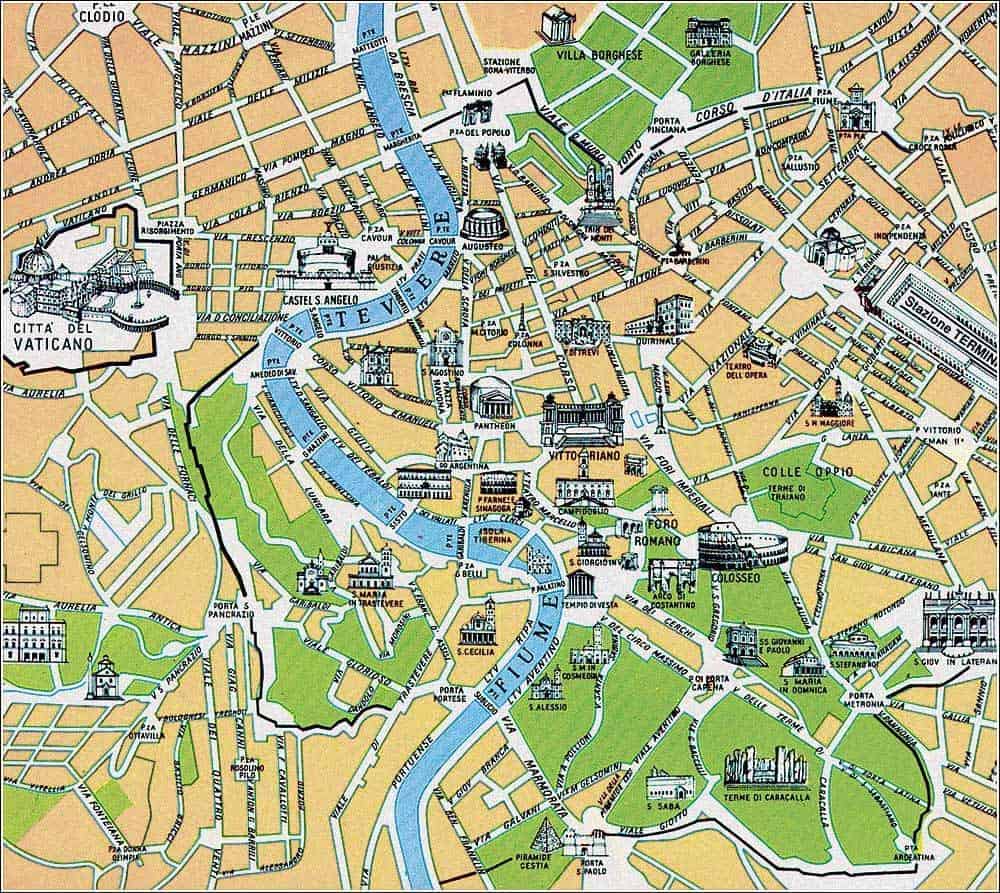

Rome is one of the few major cities in the world — in fact, I can’t think of another — where you can walk across town without ever walking down a busy road. I know. I did it the other day. I walked from the Termini train station on the east end of town to Vatican City, on the west end, and never once walked down a street where horns blared and traffic crawled.

As a seagull flies, the distance between Termini and Vatican City is only about three miles. However, I zigzagged my entire way, not only staying on side streets but also discovering interesting sites hidden in the plethora of the city’s nooks and crannies. I covered 7.5 miles. It took nearly seven hours.

That’s how many hidden points of interest this city has. Walking across Rome is like walking through an outdoor museum lined with 3,000 years of history, abstract gift stores and the world’s best food.

I saw a shop covered with terracotta busts for sale. I saw a church holding the entrails of a dozen popes. I saw the former home of the Catholic Church’s last executioner. Along the way I had the world’s best cappuccino, had a fantastic lunch in a tiny, newly discovered piazza and passed a half dozen new restaurants I must try before I die.

More than anything, I rediscovered my love for my adopted city. It’s one I recently trashed for its trash, bitched about its bureaucracy and protested its public transportation. But every city has its civic embarrassments.

New York has the Knicks. So it all evens out.

Rome, besides its famed seven hills, has a strange layout, suitable for a city nearly 3,000 years old. In the center is ancient Centro Storico, a labyrinth of alleys pinwheeling off piazzas and bordering the Roman Forum, ruins of where Ancient Rome ruled the most powerful civilization known to man. On the other side of the Tiber River stands the Vatican where once stood marshland.

Who designed the city depends on whose history you read. It’s a quilt spanning three millenium, layered like a flat geological civic map, each area having its own individual makeup.

“Every architect and pope put their hands on the design of the city,” said Massimiliano “Max” Francia, my favorite tour guide (www.rometoursnobodygives.com) in Italy and a walking Google search on Roman history.

Francia said one man who does get credit for Rome’s ancient look is Cornelius Meyer, a Dutch hydraulics engineer who replaced the brick roads with his specially designed cobblestones in the late 16th century.

The cobblestones cover much of the city and nearly all its city center. I think I hit every cobblestone along the way. With the help of Annett Klingner’s terrific book, “111 Places in Rome That You Must Not Miss,” here is what I found.

***

At 9 a.m. I left my apartment in Monteverde, the neighborhood fascists transformed from said marshland into a chic neighborhood in the 1920s. It was a glorious sunny day about 55 degrees, perfect for a long passaggiata, the Italian oft-used word for “stroll.” Wearing khaki shorts and a black T-shirt, I shed my red A.S. Roma sweatshirt after only 20 minutes.

I took the bus and subway to my starting point. Termini was my first entry to Rome in 1978, back when I was a scruffy backpacker living on $15 a day. Back then Termini was a dark, foreboding, intimidating den of thieves and shysters. In preparation for Jubilee 2000, however, the old gray lady received a facelift. In the massive main hall came high-end shops and glass-encased boutiques. Then in 2012, 7,000 square meters of public services, from cell phone stores to a food court, transformed Termini into a great place to just hang out.

I made a beeline for Mercato Centrale Roma. the 2016 addition which features 18 food stalls ranging from a coffee bar to fresh seafood. It even has a beer garden. As soft rock flowed from a loudspeaker, I ate a creamy chocolate cornetto for 1.60 euro while mapping out my route across Rome.

The area around Termini is somewhat seedy. A few years ago a female friend got knocked down and robbed walking alone at night behind the station. The homeless who often sleep along the walls didn’t wake up to help. Across the street in front of the station is filled with basic hotels, crowded coffee bars, kabob shops, cheap souvenir stands and hawkers selling everything from city tours to selfie sticks. In this neighborhood, only the train station is a destination.

Or so I thought.

I crossed Via Giolitti, the main street bordering Termini, and into one of the relatively quiet side streets, Via Cattaneo. I passed two lovers wildly making out next to an iron gate surrounding one of the most under-appreciated buildings in Rome. The Giardina Casa dell’Architettura was built in 1887 as an aquarium and fish farm for what was then a growing bourgeoisie in this Esquilino neighborhood. With its elliptical base and two symmetrical stairways leading to the niche arch entrance, it looks like an ancient Roman temple, curiously next to a train station.

I walked down Via Principe Amedeo, a taxi lane lined with outdoor cafes under protective plastic, like large cages where specimens feed. I walked past Rome’s opera house, which pales in reputation and architecture with Milan’s Scala but still beautiful in its simplicity, hidden in the warren of back streets not far from teeming Via Nazionale, one of the main arteries leaving Termini.

I looked up Nazionale as I skipped past it and saw a massive demonstration in huge Piazza Repubblica a block away. About 1,000 people waving various labor union flags were set to march on the nearby Ministry of Economic Development to protest U.S.-based Whirlpool laying off 1,350 workers from its Rome plant. Bored riot-proof police stood guard. In Rome, demonstrations happen as often as soccer games.

I continued, the chants fading in the quiet shadows of another side street.

On Via Torino, a small open door revealed one of the most astonishing art stores in Rome. Terracotta Persiani is an outdoor market covered with terracotta artwork of every Roman motif. Gods. Emperors. Nudes. Wolves. Any kind of Roman bust throughout history could probably be found on the stacked shelves and scattered around the gravel floor. There are wash basins and cat ring trees, flower boxes and signs.

This market has stood since 1804 and Domenico Persiani has been copying antique objects and doing his own designs for 30 years. Originally, the market supplied art for Rome’s aristocracy and even the popes’ summer palace. The prices looked reasonable. I saw little plaques for 25 euros and large friezes for 50. Then I remembered.

Christmas is less than two months away. Who can’t use a terracotta wild boar?

I walked down Via Modena and on the corner of Via Napoli stands the huge Carabinieri headquarters, which spits out all those cops in Armani-designed uniforms with the pointy hats and bright red stripe down the pants. I approached the front gate and one of three cop/models on the other side approached just as fast.

“Sto solamente guardando (I’m only looking),” I said, suddenly realizing what a hapless tourist I must look like.

“NO!” he said with no need of translation.

I turned heel and walked into Monti, arguably Rome’s hippest neighborhood. I’ve taken Italian classes here and often stuck around to explore the narrow streets that always found their way into a quaint piazza or designer chocolate shop or rowdy bar. I walked down quiet Via Palermo past the small door leading downstairs to Indian Affairs, my favorite Indian restaurant in Rome and one of the few ethnic restaurants (I’m serious) in the city. The overstuffed chairs and decorations make you feel like you’re in an Indian grandmother’s home but with dark lighting to add a romantic touch.

I followed a 30-foot brick and cement wall along a narrow and empty Vico di Mazzarino leading to Via del Quirinale, one of the widest boulevards in Rome. Across the street is Quirinale Hill, the highest of Rome’s seven hills and home to the Quirinale Palace, built on this hill in 1583 to get as far away as possible from the stench of the Tiber River below. The palace, at 110,500 square meters the ninth largest in the world, has housed 30 popes, four kings and 12 Italian presidents. That doesn’t include one emperor named Napoleon Bonaparte who planned on living there until his army was flattened in 1814.

I walked down the palace’s wide steps to Via della Dataria into the heart of tourist hell. Trevi Fountain sits in a giant maw within a network of crisscrossing alleys. Regardless of the year, from sunup to nearly midnight it is cheek-to-jowl tourists, all preening for selfies or throwing coins in the fountain, following the age-old and silly belief that a coin in the drink means you’ll return to Rome some day.

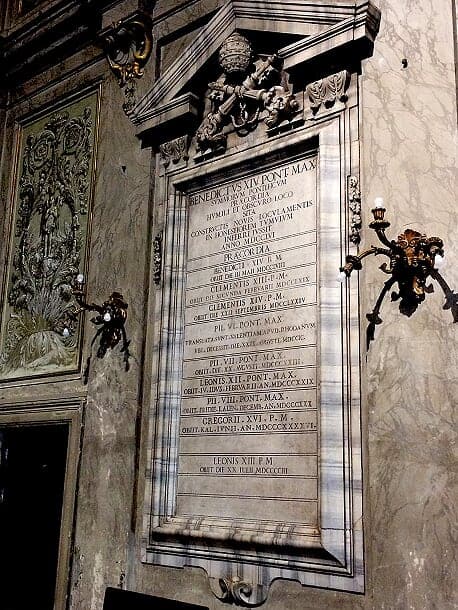

I was more interested in the unassuming church in the corner. Chiesa Santissimi Vincenzo e Anastasio, built in 1650, doesn’t rank high on Rome’s eye-pop meter, churches category, but it may on the gore category. Inside, urns on a narrow aisle contain the inner body parts of about a dozen popes. Two plaques near the altar make mention to paraecordia, Italian for innards. At one time, the bodies of deceased popes were on display for several days. From the 16th century to 1870, the popes lived in the nearby palace and this church became a convenient place to post the dead popes.

Before embalming came into vogue, you can imagine how the stench drove away a few pilgrims, particularly in summer. The church decided removing the intestines solved the problem.

I walked down the aisle of the church, so quiet compared to the din outside I thought I thought it was sound proof. I walked past a nun, holding a cane, staring blankly at the altar. I wondered if she knew we were near the containers of the heart, stomach, liver, spleen, pancreas, intestines, kidneys and lungs of some of the most famous men in Rome.

Oddly, I was hungry.

Leaving the church, I squeezed my way through the cell phone-toting, ball-capped mob past the endless line of souvenir stores, gelaterias and touristy restaurants. I walked past inviting Baccano Vineria e Ristorante, one of Rome’s most traditional Mediterranean bistros which has catered to the Roman aristocracy for more than a century.

Instead I passed through the 16th century Galleria Sciarra, a five-story, open-air building with an airy square in the middle and decorated on every wall with frescoes from the 19th century depicting sophisticated women of Rome, wearing the fashion of the day.

I ventured toward Rome’s other tourist mecca. But every time I approach the Pantheon, the rotund 126 A.D. church that remains one of the world’s architectural marvels, I stop just short on the side street of Via degli Orfani and enter Tazza d’Oro. Before I moved to Rome in 2014, The New York Times wrote this cafe has the best cappuccino in Rome. Not always genuflecting to Times hype, I was skeptical when I entered the first time.

The Times was right. After seven years in Rome over two stints, I have yet to find a bar with cappuccino that matches the creamy consistency of the milky foam and the smoothness of its coffee. Despite its proximity to the Pantheon’s mob scene and a 1.10 price tag and the massive sign on the facade, it’s never terribly crowded. I bellied up to the bar with a small group of Japanese who always seem to make up 50 percent of the clientele.

I passed through the Pantheon but while a posse of East Indian tourists posed for a photo in front of the church and tourists packed the 13 overpriced cafes and trattorias in the piazza, I stopped and stared at a plaque Klingner’s book pointed out.

It’s from 1823 and reflects Pope Pius VII and his disgust with all the low-rent restaurants in cheap, wooden huts in front of the Pantheon. Seeking a more airy look suitable for a church of this magnitude, Pius had them all demolished. The plaque reads, “In the 23rd year of his pontificate, Pope Pius VII wisely had the area in front of the Pantheon, which was occupied by in-elegant taverns, freed of its disfigurement, permitting a clear view of the place.”

I wondered how Pius would feel about the Bangladeshi hawkers tossing high in the air splotch toys splatting on the cobblestones.

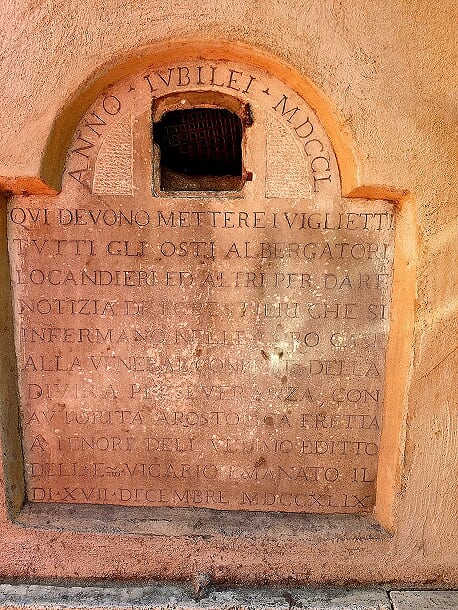

The beauty of living in Rome is after seven years I still run into piazzas and small streets I’ve never seen before. It’s like a new vacation every day. Just two blocks from the packed Pantheon down small Via delle Coppelle is Piazza delle Coppelle. Tucked away almost hidden from the street, the U-shaped piazza has been the site of a fruit and vegetable market since the Middle Ages. On San Salvatore delle Cappelle, a church built in 1195, stands a marble plaque from the mid-18th century bearing the oldest Italian inscription in Rome. As ordered by the pope, it tells people that if they know any sick foreigners, they must report it in writing to the church. The plaque still has a slot to insert the letters.

When I walked into the piazza, they were still selling fruit and vegetables but what got my attention were two little outdoor trattorias. At Osteria di Mario I took a table next to two couples from Texas, the only tourists I saw in the piazza. On a beautiful, sunny, 67-degree day, I had a lovely rigatoni carbonara, a glass of Montepulciano d’Abruzzo and coffee. Total price: 15 euros. That’s about the price of a cappuccino in front of the Pantheon.

By the time I digested and soaked up some sun, the cafes were packed with lunching Italian businessmen in sharp suits and shiny shoes, chatting on their cell phones in between bites of pasta.

I headed south into the heart of Centro Storico. This is what separates Rome from every major city in the world, why it’s better than Paris and London and New York. No place has an historical center this big with only one main street. Corso Vittorio Manuele slices through the middle of Centro Storico. On the south side is the old vegetable market and execution ground turned party central, Campo dei Fiori, and on the north side is the majestic Piazza Navona a short stroll from the Pantheon. Along the way are oft-overlooked piazzas such as Piazza della Minerva, where a jeans-clad woman flutist played a lovely rendition of Elvis Presley’s “Can’t Help Falling in Love with You.” Nearby stands Rome’s smallest obelisk, a 19-footer on the back of an elephant. It was brought from Sais, Egypt, and placed on the site of an old Egyptian temple built to commemorate Cleopatra’s arrival in Rome in 135 A.D. Ancient Romans were huge fans of Egyptian culture. They believed they were the origins of their own culture. In fact, a 120-foot-high pyramid was erected in 76 B.C. in my old neighborhood of Testaccio.

I walked past Torre Argentina, with remains of four Republican temples and and where Julius Caesar had his last business meeting end with his colleagues stabbing him 23 times. Today, a cat sanctuary attracts cat lovers, such as myself who wandered down the steps to pet the fat, happy kitties who sun themselves and sleep on all the marble ruins. If you’re not careful, they’ll jump on your lap and fall asleep before you can alert authorities.

Thirsty from walking for about five hours, I went down one of my favorite streets. Via Governo del Vecchio is a cobblestone alley that leads to Abbey Theatre Irish Pub, my home away from home. It’s my Cheers, where the international collection of bartenders and waitresses always know to serve me my Reale or My Antonio Italian craft beer when I enter. They have a room upstairs for me and my fellow Romanisti to watch our beloved A.S. Roma soccer team. Abbey also serves the best pub food outside the UK.

I looked outside at the sunshine and thought, What a great day. What a great day sit inside a pub and watch a Barcelona-Inter Milan replay with an Italian beer.

Energized, I continued down Governo del Vecchio, past the the great antipasti restaurant, Papi Prosciutteria. and Caffe Novecento, the elegant caffe with designer cakes where I’ll read the paper before Roma games.

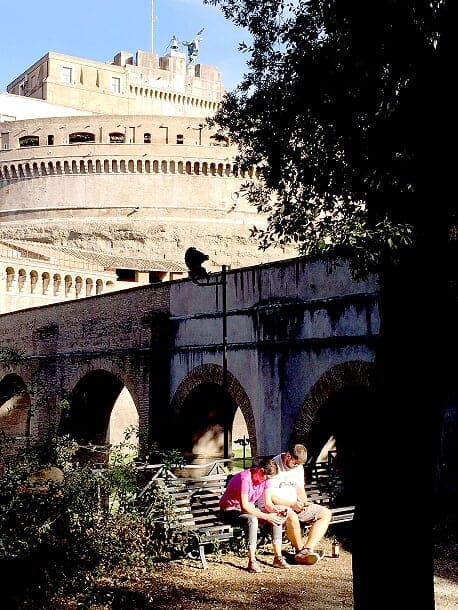

Zigging and zagging, I made it to the Tiber River where I crossed Ponte Sant’Angelo to the entrance of Castel Sant’Angelo, the behemoth mausoleum Hadrian built in 135 A.D. The views from inside are among the best in Rome but the history is truly creepy. Castel Sant’Angelo was used first as a mausoleum then as a fortress, then later as an escape for popes from the stress of life at St. Peter’s up the street.

The papacy sexual history is rife with scandal, groupies and pedophilia. Popes would sneak their concubine down a hidden stone passageway stretching from St. Peter’s to Castel Sant’Angelo. One time inside I saw the pope’s bedroom and wanted to go take a long, hot shower. This time I walked along the stone passageway, still feeling creepy after all these years.

However, near the end of my walk came a true highlight. Off Via della Conciliazione, the huge boulevard Mussolini cleared out for a breathtaking, open-air view of St. Peter’s, is an alley called Vicolo del Campanile. The first door on the left is the former home of Giovanni Battista Bugatti (1779-1869), known as Mastro Titta. He is the legendary last executioner for the Catholic Church. From this apartment, he walked out and executed 516 people, mostly by beheading, from the early to mid-19th century.

He wasn’t a bad guy, doing his job as “God’s will.”. According to Klingner’s book, “In quiet periods Bugatti led a modest life, happily married and painting parasols for tourists.” He often smiled and made the cross at frightened passers by. He “spoke calmly to those condemned,” Klingner wrote, and even offered some snuff before he snuffed out their lives. His ax is in the Museum of Criminology near Campo de’ Fiori.

At 4:51 p.m., I finally touched one of the columns surrounding St. Peter’s Square. I walked 7.5 miles and barely heard a car horn. With the exception of a couple touristy piazzas, I spent nearly seven hours in quiet serenity. I needed a glass of wine to toast Rome’s popes and architects, its builders and thinkers, its emperors and laborers.

Grazie mille, amici. Bravi. The layout of your Eternal City truly is eternal.

October 8, 2019 @ 9:55 am

Great article John – makes me want to get on a plane!

October 8, 2019 @ 12:05 pm

Really well done; although I have been here since 1992, I still get a thrill from discovering new places, and you definitely identified some.

October 9, 2019 @ 10:02 pm

One of your best articles John! I used to work at the USO when it was on Via della Conciliazione in 1980. I used to walk the American troops down to St. Peter’s every Wednesday morning to see the Pope, with my big USO flag hahaha good times! I never knew that about Bugatti the executioner, but I shall check it out next visit!

October 10, 2019 @ 5:11 am

Thanks for the kind note. That scene walking down Conciliazione would be quite a sight, almost mirroring Mussolini doing the same with Italian troops. I think that’s one reason he opened up that neighborhood. I may write a blog about Mastro Titta. Hey, it gives me a good excuse to check out the dive bar named after him.

October 9, 2019 @ 10:49 pm

I did this same thing though in reverse. After leaving the Vatican Museums I just sat out and kept walking – I figured I could always find a cab. It was a beautiful experience, along the alleys, seeing the gear of priests, incredible antique shops, paper shops and just the beauty of Rome. I was pretty grateful to get to Piazza Navonna in familiar territory (could have kissed the ground I must have walked 20 miles!). Stopped in and had a double espresso to sit and watch (sit) and kept going until hitting Centro…then enjoyed the best Guinness ever with a cheeseburger and fries (something I would never do normally). Life is beautiful, especially on foot with

October 10, 2019 @ 5:09 am

Best Guinness ever? In Rome? Where did you find it? Centro is Mercato Centrale? I take it you haven’t been to Ireland. I stick to Italian craft beers but you should try the Guinness at Abbey Theatre pub. It gets good reviews. Thanks for the note, Toni. Thanks for promoting the proper way to travel.

October 10, 2019 @ 10:50 am

Scholars Lounge (Via del Plebiscito) great place – been named best Irish Pub in the world. Had a most excellent conversation – In Rome, In an Irish Pub, with a Frenchman about American Democracy and if it could hold under current circumstances. Brilliant crowd. I have had the privilege of spending 3 weeks in Ireland – Letterkenny (NW) and it is stunning, and the Guinness great there too – especially when watching GAA football with the locals. I’ve been to the Abbey Theatre – it’s quite like Ireland and very nice.

October 12, 2019 @ 7:50 am

We used to walk from Parioli to Campo de’ Fiori every Saturday, quite early, and enjoyed that same calm and the ability to wander through history, stop in a locals-only spot for espresso e cornetto, do our shopping outside of a supermercato. That is one of the things I miss about Rome. Thanks for reminding me of the good stuff. The trash, the bureaucracy: not so much.

October 13, 2019 @ 11:33 am

Sensational description of one of the most amazing cities in the world. We visited Rome in 2011, and 2017. There is not enough time to see everything, and not enough words to fully describe it. Thank you for the beautiful prose and pictures.

October 14, 2019 @ 5:36 am

Thank you for the kind words. I may do it again next year and take a different route.

October 14, 2019 @ 8:38 am

Enjoy:)

October 16, 2019 @ 1:22 pm

Walking in Rome is always a new experience. I thought you might like this. https://writingroma.wordpress.com/2019/10/16/bonus-vernonlee-the-spirit-of-rome-describing-the-pantheon-from-sopraminerva/

October 17, 2019 @ 12:34 am

Great photo! Thank you!

October 16, 2019 @ 1:22 pm

Walking in Rome is always a new experience. I thought you might like this. https://writingroma.wordpress.com/2019/10/16/bonus-vernonlee-the-spirit-of-rome-describing-the-pantheon-from-sopraminerva/

October 21, 2019 @ 11:24 pm

Love Rome!

February 6, 2023 @ 1:51 pm

Monteverde Vecchio (and pockets of Monteverde Nuovo) was actually transformed by Mayor Ernesto Nathan, a close confidant of Mazzini and definitely not a fascist. Nathan, whose father was English, was responsible for the planning regulations of 1912 (he was mayor between 1909 and 1913) that encouraged low rise villa style apartment blocks with gardens around then that make Monteverde so pretty. It is also a mountain so no marsh problems.

The fascist intervention was along the area of Via Donna Olimpia, that sort of divides Monteverde Nuovo and Monteverde Vecchio, which is low lying and where tall public housing was built in during Mussolini’s time. Lovely article but I though you might like this extra info.