Anniversary in Venice: A beautiful city in turmoil

VENICE, Italy — It’s a sunny May morning, and Marina and I are sitting in the lap of opulence. Marina isn’t a high-maintenance traveler. She doesn’t need five stars on a hotel’s front door or china with her airplane food. She likes a breakfast buffet. That’s about it.

But in Venice, where we are celebrating our three-year anniversary, we find ourselves in a 16th century palace. A real palace. The huge living room has large oil paintings over elegant couches we can see in the reflection of the wall-to-wall mirror. Outside the window we hear the warbling of a tenor serenading a Japanese couple in a gondola below. Our bedroom is old, stained wood with a king-size bed and old portraits of ancestors who lived here in past generations.

This palace, or palazzo in Italian, was built in 1600. It was the time when Venice had receded as Europe’s greatest naval power into the cushy role as perhaps Europe’s cultural capital. It had charged from the Renaissance to the Baroque period with flashy paintings and contemporary music. Not that it had become a full-fledged tourist destination, but it also had 12,000 registered prostitutes.

It’s 400 years later and the owner of the palace sits by the window. The sounds of a steady parade of tourists crossing the small bridge over the narrow canal below us drift into the room. Gianni Piani, 54, grew up in this palace. He still lives here. But Venice is changing. Piani is changing with it.

“I am in love with Venice,” he says. “But for my family it’s impossible to live here.”

Marina and I have been to Venice many times before but never together. I’ve always maintained it’s the most romantic city in the world and my previous visit in 2015 did not dissuade me. Neither does this one. You can’t overestimate the positive absence of cars in a city built on 118 tiny islands. Sipping a spritz, Venice’s signature drink, on a small, quiet canal. Turning a corner onto a narrow, cobblestone pathway to see a fisherman mending his nets. Hearing accordion music while munching cicchetti, Venetian antipasti, as the sun sets on the water.

It’s like living in a science fiction movie where a world has banned the evil automobile and people are falling in love around every corner.

Unfortunately, in Venice the science fiction movie is headed for a tragic ending. Remember “Escape from New York”? Call it “Escape from Venice”: Terrorized inhabitants wildly flee a city before evil invaders sink it under the sea, never to be seen again.

In the height of the Venetian Empire in the 14th century, Venetians fended off Genoa and Hungary. In the 21st century, it’s losing to a new threat, one that has gone from friend to foe.

Tourists.

According to CISET, the International Centre for Studies on Tourism Economics, Venice had 25 million tourists in 2016. That’s nearly 50,000 a day. That’s just under its current population of 54,000, a number that will likely drop even more after you finish reading this blog.

In 1931, it had a population of 164,000. When I first visited Venice as a 22-year-old backpacker in 1978, it had 2 million tourists. Marina calls Venice “The city for lovers.” True. But it’s also a city for people with Yankees ball caps, backpacks, selfie sticks and fanny packs, most following tour guides holding little flags. On Sunday and Monday this past Easter weekend, 220,000 tourists poured into Venice.

“Forty years ago there were more tourists of higher quality,” Piani says. “Artists, intellectuals and so on. Now we have tourists who come in the morning, they spend five euros, they dirty the town and go away.”

This year alone, two tourists were arrested swimming in the canal. Two drunks were seen dancing near the hallmark Rialto Bridge. Public urination is common. I can also confirm, so is public drunkenness.

Piani is pissed. He’s not alone. In July, an estimated 2,000 Venetians took to the streets — and lagoon — protesting the uncontrolled tourism, claiming it has destroyed their quality of life. Piani agrees. When he was a child in the 1960s, he played soccer in the streets and rode his bike freely along the narrow pathways. His father swam in the canals.

That was before nine or 10 cruise ships started docking here daily, some with 40,000 passengers.

“The school of my kids, it’s impossible to reach,” Piani says. “We need to wake up very early to arrive on time because the vaporettas (public transport boats) are always full of tourists. Going there on foot is impossible because you have to cross the town, skipping groups of tourists or the cruise ships.”

Mayor Luigi Brugnaro, a stylish, independent 56-year-old businessman who also owns Venice’s popular pro basketball team, has come under heavy fire for not fulfilling campaign promises of stemming the problem. He has loudly talked of charging day-trippers and installing turnstiles and barriers to redirect tourists to lesser-visited sites. Locals would carry a Venezia Unica card to move about freely.

Governments have struggled to pull the trigger on such measures due to the city’s economic dependence on tourism. But Brugnaro sounds like one of the people, telling Corriere della Sera, “The mayor must have power to close the city off on crowded days.” Once a British couple complained to his office after getting charged 500 euros for a seafood dinner near St. Mark’s Square and a Japanese couple was charged 120 euros for lobster pasta. Brugnaro called them, on the record, “cheapskates.”

But the rise in tourism has made Venice one of the most expensive cities in Europe. I learned that first hand after we checked in and I quenched my thirst with a bottle of Peroni in a simple, tiny cafeteria. Peroni is the Budweiser of Italy, a beer you can get for 1.50 euro in working class bars in Rome.

I paid 4.50. Piani says the day before he bought 10 apples for 12.50 euro. But it’s not just the day to day prices that is turning Venice into a theme park. Tourism has made renting more profitable than owning. Piani has another house he had while in college that’s 75 square meters and rents it out for 200 euros a day. I feel I’ve got a bargain paying 150.

Many Venetians have left their family home to less expensive places in Cannaregio, near the Jewish Ghetto and the train station, or Mestre, the last town on the mainland before the four-kilometer bridge takes you to Venice.

“Young people nowadays, or as it happened to me, they inherited a palace,” he says. “Otherwise, what do they do? Where do they go? In Mestre you can buy a flat with 120,000 euros and can sell a 50-, 60-square-meter house in Venice at 500,000-600,000 euros.

“I have a friend who lives in Sicily now. He owns a palace, a really beautiful palace at Rialto (Bridge). His daughter doesn’t want to deal with that house any longer. She lives in Mestre in a modern flat of 80 square meters and she never goes to Venice.”

However, there is a reason 25 million tourists come here a year. Venice is drop-dead gorgeous, still. If you know where to go, as Marina and I do, you can have a tranquil, romantic weekend without dining next to some accountant from L.A. As I’ve written before, the key to visiting Venice is get away from the Grand Canal. Its inlets are logjammed with gondolas. Its sidewalks are cheek to cheek tourists. The vaporettas bouncing back and forth at the stops are big and crowded.

Walk two minutes and you’ll find a quiet canal. We ventured to one of my favorite neighborhoods: Cannaregio, in the north end and home to the Jewish Ghetto and some of the most authentic local food in Venice. We hung out at two lovely, quaint wine bars on the Rio di San Girolamo. Al Timon and Vino Vera have nice picnic tables on the narrow canal with a little bridge that had a fraction of the foot traffic of the one outside our room. We sipped spritz, a Venetian invention made with bittersweet Aperol, Prosecco and soda water, and Pinot Grigio, one of the hallmark wines of Venice’s Veneto region. We munched on cicchetti of goat cheese and sun-dried tomatoes on bread, and prosciutto, brie and bell peppers on bread.

The forecast rain never came and we watched Venetians floating home on quiet motorboats as the sun set behind the bridge. Hey, can 25 million tourists be wrong?

The next night we dined at Osteria da Alberto. It’s in Cannaregio on that iffy edge where the crowds from Rialto stretch inland. Rialto is a mess, a pedestrian traffic jam, the Fifth Avenue of Venice. So many selfie sticks hover over the bridge it looks like it’s covered with miniature TV antennas. But we weaved through the maze of alleys and souvenir shops to a small bridge no more than 10 feet long. We looked down a tiny canal lined with centuries-old buildings of yellow, red and orange.

Next door at Alberto’s, old pots hung from the ceiling and local knick-knacks and black and white photos of old Venice, the Venice before cruise ships, hung on the walls. Soft jazz played on the loudspeaker. Marina noticed everyone around us spoke Venetian. I had a nice orata, or sea bream, which came out as a whole fish and Marina skillfully filleted.

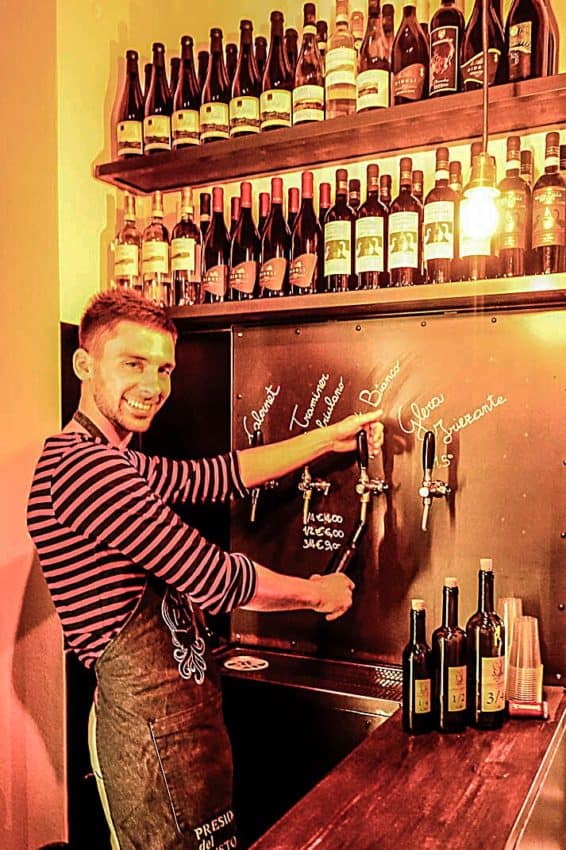

Working our way back to the Grand Canal, we found the darkest of Venetian bars. Sepa, Venetian for cuttlefish, is a tiny hole in the wall with two huge wine barrels serving as tables next to a whole display case of cicchetti — sardines, meatballs, little ravioli. Around the corner, a waiter filled a half-liter bottle with Pinot Bianco which he poured from a spigot in the wall. Marina and I stood in a dark alley listening to Venetian we couldn’t comprehend while she patiently waited until I finished the wine.

Every trip to Venice is a new discovery. You get that with 118 islands. Marina and I went to one of the bigger ones for one of the most tranquil experiences we’ve had here. Lido was once a magnet for the European rich and famous in the 19th century. Walking the quiet streets you can still see the massive villas they bought all now sporting pointy, iron fuck-you fences.

But the last stop on the vaporetto line is well worth the trip, especially in May. It’s before the long, white-sand beaches get busy in June and the Venice Film Festival begins in September. With the beachwear shops, the mansions and the lovely tree-lined boulevards, it felt like Newport, Rhode Island, before the crowds come. A short bus ride to the north end put us in the Aurora Beach Bar where we sipped spritzes and watched a black immigrant putting lanterns in the Israel olive trees shading us for the disco pub later that night. Alice Merton’s “I’ve Got No Roots” played on a loudspeaker. Only two other people lounged on the beach chairs as the sun splashed off the Adriatic Sea just beyond.

A short walk away is the Palazzo del Cinema where Hollywood’s elite gather to preview the next year’s top films. Unfortunately, the experience of being on the same steps as Steven Spielberg, George Clooney and Dustin Hoffman evaporates in light of a building that looks like a fascist airport. It’s a long chalk white, two-story monstrosity void of decoration. Its lack of imagination belies the imagination it shows inside.

Lido’s highlight, instead, is Malamocco. Called “The Little Venice,” it’s a neighborhood on the east end that’s a series of narrow canals. On this Saturday, it was deathly quiet. Not a soul in sight. We walked past a piazza with mineral water in buckets and a wedding inside a church. Down the alley we sat down at a great trattoria that’s a local watering hole. Al Ponte di Borgo is a crude pink building with a green awning and so dark inside I almost needed a flashlight to find the bar. It’s self service where I pointed to the octopus salad behind a display case. Two overweight, loud men behind the bar pulled out two big unlabeled jugs of red wine from a cooler. No menus. No English. Not even any Italian.

This was real Venice, unvarnished and unabashed.

Marina had a heaping fried fish platter and my octopus salad was a gnarly mess of tentacles. And very fresh. How fresh? The octopus still had shit in it. Yes, you read that right. It was real shit. And I did try it. It tasted like … well, shit. But the the rest of the meal was great and we chatted with the table of Venetians who talked about how Roberto Salvini, the leader of the fascist, racist La Lega political party that’s gaining a foothold in government, will lead Italy from its abyss.

We left Venice the next night vowing to return, undeterred by the crowds, the prices, the hassles. Venice is one of the most unique cities in the world, the most romantic city in the world. I’ll never tire of returning. But I haven’t lived here 54 years. I never played soccer in the streets or swam in the canal. Piani has. He also has a plan.

He’s moving to Sicily.

May 11, 2018 @ 9:04 am

In ten visits to Venezia we have found many °back doors° where tourists seldom tread, but have not (yet) made it to the Lido. Next time!

May 13, 2018 @ 9:58 am

Your article brought up so many thoughts and emotions for me. I’ve owned a home and have lived in a tourist town in the Caifornia Sierra Mountains since 1997. The influx of tourists on the weekends and holidays is really challenging, particularly for me since my work livelihood does not depend on it. My Italian cousins own a flat on the Lido across the lagoon from Venice which you highlight in the article. I visit them there most years, staying in Dorsoduro, my favorite sestiere. Like at home I resent “i turisti” (of course I too am one in Venice). The key is not acting like a tourist. I dress respectfully and smartly. When my husband or best friend travel with me, we walk single file on narrow streets so residents can easily pass. I pay to eat in dining establishments, not hang out on the streets blocking passageways. Like where I live pleasantries go a long way. Just because one pays money to be there doesn’t give license to be rude or insensitive to culture. I’ve lead a couple tours in years past and prior to arriving in Italy gave focus to learning simple phraseology…saying buongiorgno, salve, etc., and alway asking “permeso” before barging into a store or touching a piece of fruit. I could go on and on as I have so much love for Venice. I have my hidden gems and can navigate away from the crowds while there on vacation, but have empathy for the Venetians who struggle with mass tourism on a daily basis without solutions.

November 14, 2020 @ 5:28 pm

My Italian partner always speaks badly about Venice and its tourism. But like you, I know the ghetto area and the Lido, which are still lovely and peaceful. It will be great to return, once Covid is gone from Italy! By the way, we live in Lucca. See our magazine at http://www.luccagrapevine.com

May 15, 2018 @ 6:41 am

Thanks so much for the nice email. I’m glad some responsible travelers still treat Venice with respect. I always will.