Barolo: My love letter from the vino paradiso of Le Langhe

BAROLO, Italy – Everyone who dreams of Italy dreams of a specific place here. It’s like a scene from a romantic movie, one that continues in a loop through your head until it happens. Then you realize the reality surpassed your dream. Riding a gondola through Venice. Seeing the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican. Sitting on your cliffside balcony overlooking the Tyrrhenian Sea in Positano.

After living in Italy for more than 10 years over two stints, I finally made my dream come true.

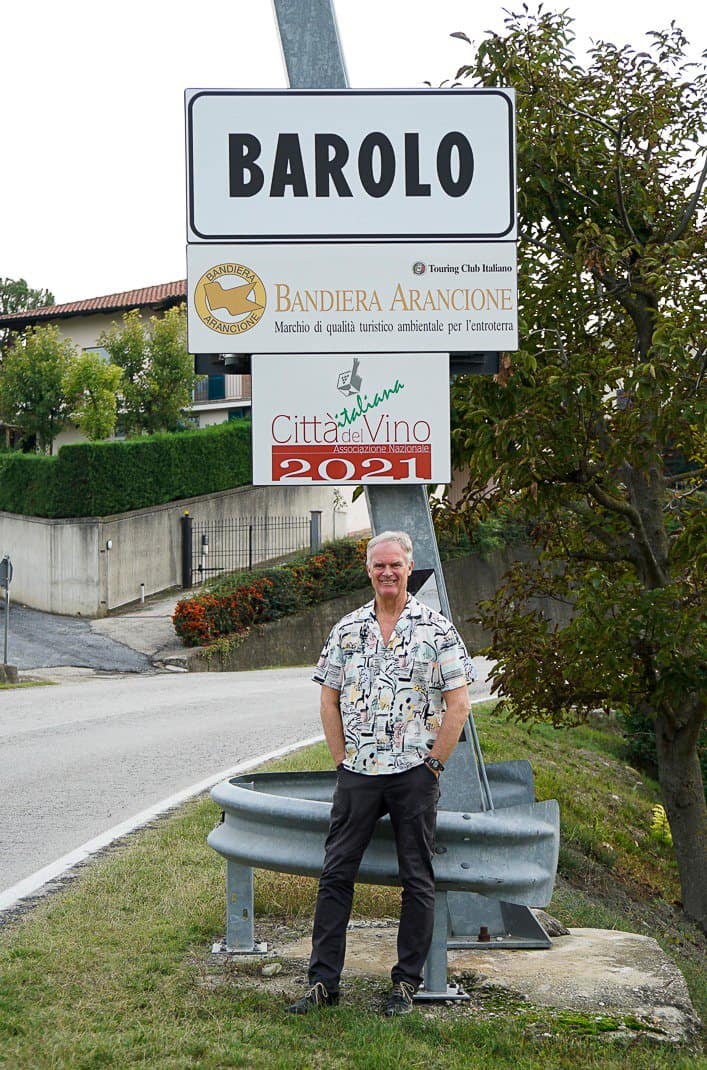

I had a glass of Barolo in Barolo.

I’ve had chateaubriand in Chateaubriand, France. I’ve had a sandwich in Sandwich, England. But nothing surpasses drinking my favorite wine in the world in its birthplace. Last week, I made it happen. Yes, it did surpass my dream. Every time I drink Barolo it’s like a dream.

Why my favorite

Barolo is my king of the world’s red wines. It is so robust, so full of fruits and spices, every sip explodes down your throat like a waterfall of berries, cherries and plums, all sprinkled with cinnamon. Regular pasta, no matter how finely prepared, isn’t worthy of Barolo’s strength. Florentine steak. Risotto with truffles. Gnocchi in gorgonzola sauce. Only robust dishes like these can be paired with a wine this complex.

Barolo is the wine for celebration and romance. Locked down in Covid hell on my birthday in March 2020, I drank an entire bottle alone in my flat in Rome while Marina, although a teetotaler, looked on enviously during our video call. Barolo is what I drank when Roma beat Barcelona in the 2018 Champions League and when I sold my first story to The New York Times.

But it should be shared. Who can’t be in love when they’re drinking Barolo? As the Italian writer and poet Cesare Pavese (1908-1950) once wrote, “Barolo is the wine to make love on winter days, but these are things that only women understand.”

What do I understand? If you took a thousand cases of Barolo to Ukraine and gave them to the Russian and Ukrainian soldiers, you’d end the war in a week. The two sides would grasp shoulders, clink glasses and toast “Na zdorovie!” and “Budmo!” until they forgot what they were fighting about.

Barolo makes everyone happy. It does me. I first discovered Barolo in 1998 on a vacation to Rome. I’d just been dumped by a Brazilian lingerie saleswoman from Zurich (long story), and decided to have a glass of wine before I threw myself in the Tiber.

Back then Campo de’ Fiori had a little wine bar called Vineria. The most expensive glass on the list was something called “Barolo.” I’d never heard of Barolo. It was only 10,000 lire (about $5 at the time) so I tried it.

It was the best glass of wine of my life. I’d never had a glass so full of flavor. Suddenly, I forgot about lost love and found new love in this wine. The filthy Tiber went from looking like my burial ground to the Seine in spring. Barolo helped me fall in love with Rome and led me to moving here.

Twice.

All this time I dreamed of visiting the town of Barolo. It’s to wine lovers what the Vatican is to Catholics. So last week Marina and I hopped in her car and drove north 390 miles (650 kilometers), with a one-night layover in Lucca (blog coming in two weeks), into the region of Piedmont.

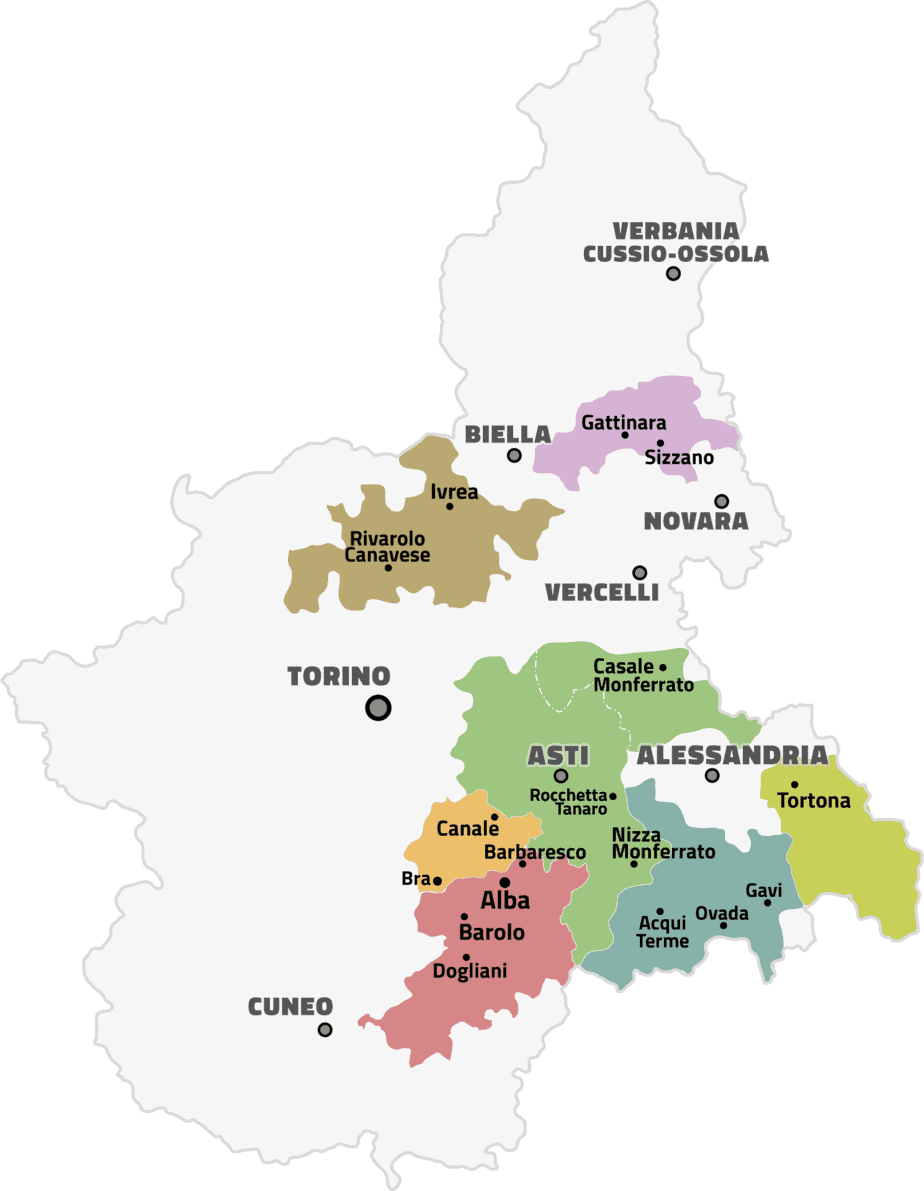

Le Langhe

Barolo is in a zone in Piedmont’s southeast called Le Langhe, about 30 miles (50 kilometers) southeast of Turin. It’s in the foothills of the Alps and the mountain soil gives the grapes their distinct flavors. If the Barolos I tried over three days blew me away, Le Langhe’s beauty had the same effect. Le Langhe looks like a giant green quilt of undulating grapevines, deep valleys and gentle hills. Medieval castles stick up over morning fog like a science fiction movie set.

Our base was the lovely Poggio dei Farinetti B&B in the village of Diano d’Alba (pop. 3,600). It’s just north of Alba (pop. 31,000), Le Langhe’s main city. Every morning, we woke up and stepped onto the balcony overlooking the pool. Beyond were nothing but grapevines stretching off to the horizon. The green rows rolled up one side of the valley and back up the other side.

To our right stood the 14th century Castello di Diano d’Alba, greeting us in the morning while seemingly floating on a sea of clouds. I’ve been all over Italy, from Sicily to the Italian Alps. Le Langhe, a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2014, may be the prettiest place I’ve ever been.

It got me in the mood for wine.

It would anyone. In Le Langhe, just a little larger than New Jersey, there are more than 800 wineries. Diano d’Alba alone has 42. They nearly all have tasting rooms. How do you choose? You could put Le Langhe’s winery map on the wall and throw darts. They’re all good.

The main wines

We chose four to hit leisurely over two days. Before I take you along on the tour, here’s a little summary of four wines that can confuse people:

- Barolo. A dry, red, full-bodied wine that comes from 100 percent Nebbiolo grapes. They come only from the 11 villages in and around the town of Barolo and released after four years.

- Nebbiolo. It is 100 percent Nebbiolo grape, slightly fruitier, and released after a minimum of one year.

- Barbaresco. It also is 100 percent Nebbiolo grapes but comes from the village of Barbaresco 15 miles (25 kilometers) north of Barolo as well as Treiso and Neive. It has an intense red color and released after three years.

- Barbera. Often confused with Barbaresco, it is its own separate grape. Barbera is Italy’s third-most planted grape behind Sangiovese and Montepluciano, and comes from the Veneto region in Northeast Italy. Barbera wine, filled with red fruits and spices, is sometimes called “The Barolo of Veneto.”

Notice I listed Barolo first. There’s a reason. “It is the king of wine and the wine of kings.”

Barolo history

The famous slogan is true. Barolo has deep political ties. It has knocked over kings (in a good way) if not governments. While the Nebbiolo grape dates to the 13th century, Barolo wine got its start in the mid-1800s when Camillo Benso, the Count of Cavour who led Italy’s drive to unification, wanted to improve his family estate in the Lange village of Grinzane by improving its wine making.

He hired a French winemaker named Louis Oudart who fermented the Nebbiolo grape completely dry for the first modern Barolo. Soon thereafter, noblewoman Giulietta Falletti, the Marchioness of Barolo, had Oudart develop a Barolo wine so good, King Carlo Alberto of Savoy purchased estates in the nearby towns of Verduno and Roddi for wine production.

Italy achieved unification in 1861. (See, Ukraine? It can happen!)

The wine tastings

From our B&B we were within 15 minutes from countless wineries. Here’s how we spent our two glorious days in Barolo country.

Day One

Aurelio Settimo, Frazione Annunziata 30, La Morra, 39-01-735-0803, Home | Wine Producers is La Morra (CN) | Aurelio Settimo, aureliosettimo@aureliosettimo.com, 9 a.m.-noon, 2-5 p.m. Monday-Friday.

We planned our trip in October, Italy’s traditional harvest month. However, global warming has pushed the harvest to September and sometimes as early as August. (Blog on global warming’s effects on Italian wine coming next week.)

The vines were mostly cleared of grapes but Aurelio Settimo’s setting is still astounding. It covers 17 acres (seven hectares) in little La Morra (pop. 2,500) four miles (six kilometers) north of Barolo. Davide Boasso, the great grandson of the founder, Domenico Settimo, took us up among his vines on a sunny day in the 60s.

Dominico started the vineyard in 1943 but sold grapes to the area’s bigger wineries until 1961. Then Aurelio Settimo, Davide’s grandfather, started making his own wine “and he planted vineyards everywhere in the territory,” Davide said.

Ninety percent of their production is Nebbiolo and Barolo. Seventy percent is exported, mostly to the U.S., Canada and Northern Europe.

“For the Italian market, Barolo is difficult because it’s expensive,” said Laura Cagnazzo, the office manager who has worked at Aurelio Settimo since 1999. “It needs a lot of time to be drinkable. It needs strong dishes, very tasty food. Also, we only drink Barolo on big occasions such as Christmas, a special birthday, graduate party.”

Aurelio Settimo has a beautiful tasting room. Its long table is made from used wine barrels. On a nearby shelf is a bottle of their first Barolo from 1961. Laura set up the wines for me while I asked what she liked about Barolo.

“I like Barolo because it’s an important and famous wine that helped our area to be famous all over the world,” she said. “Barolo and Nebbiolo can be grown and produced only here, only in 11 little villages.”

I tried four different wines and the best was the Rocche dell’Annunziata 2018. It was off-the-charts luscious. My wine palate isn’t sophisticated enough to differentiate flavors but Laura said it sports licorice, red berries, plums, roses, violets and cinnamon.

A bottle became my first souvenir.

Damilano Barolo, Via Roma 31, Barolo, 39-01-735-6105, www.cantinedamilano.it, 10:30 a.m.-6:30 p.m.

The winery is down a long service road just outside Barolo’s charming town center. The vineyard is on Cannubi Hill, considered the epicenter of Barolo wine. Of Cannubi’s 98 acres (40 hectares), Damilano owns 10 percent.

Giuseppe Borgogno started the winery in 1890 but Giacomo Damilano, his son-in-law and the winery’s namesake, put it on Italy’s crowded wine map.

Marcella Borgogno, no relation to Giuseppe, lined up the bottles for me. Interestingly, each bottle had a chess piece on it. The king was on their Barolo Cannubi, the top of their list. The rook was on the Liste Barolo. Why chess pieces?

“To drink Barolo is like playing chess,” Marcella said. “You have to think, meditate, wait.”

I tried the Barolo Cannubi and it popped over nearly all the others. So did the price: €156. It’s the most expensive wine I’ve ever tried and worth every centesimo. Instead, for €45 I bought Damilano’s most popular: a 2018 Barolo Lecinquevigne, named for the five vineyards it comes from.

I asked her what she likes about Barolo.

“Because it’s a very elegant wine with a soft smell like roses and violet but a very full body taste,” she said. “You can keep it for a very long period. It’s also a little bit spicy so it’s perfect for second dishes: truffles, mushrooms, meats. Especially this (truffle) season, it’s perfect.”

The tasting gave us the opportunity to explore the town of Barolo. It’s famous for its Barolo Wine Museum. Built in 2010, the multi-media museum covers three floors of 10th century Castello Comunale Falletti di Barolo, a beautiful castle with an iconic clock tower that can be seen for miles.

The museum has a small theater showing clips of movie scenes involving wine, ranging from “Dracula” to “Sideways.” It features two rooms with a continuous chronological history of wine making. Did you know:

- The Golaseccans, related to the Celtic people, developed the cultivation of grapevines on the Italian peninsula as early as the 7th century B.C.

- In the third 3rd century B.C., Egyptian pharaohs could only drink wine and it was dedicated to them during religious festivals.

- During famines, religious orders handed out wine to the starving as it was considered an essential food.

The town is also seems like a wine museum. The cobblestone streets are lined with little enotecas and black and white photos of old Barolo. One store had a case for truffles, the precious mushrooms people travel from all over the world to Le Langhe to dig in October. But only the rich buy them.

The case’s price for white truffles: €1,300 a kilogram.

DAY TWO

Produttori del Barbaresco, Via Torino 54, Barbaresco, 39-01-73-635-139, www.produttoridelbarbaresco.com, produttori@produttoridelbarbaresco.com, 9 a.m.-1 p.m, 2-6 p.m., Monday-Friday, 10 a.m.-6 p.m. Saturday-Sunday.

I wanted to try a Barbaresco to compare with my beloved Barolo. I tell Americans that if you want to impress someone but don’t have the money for a Barolo, get a Barbaresco. It’s often about half the price and almost as good.

Almost.

Produttori del Barbaresco is a group of 53 families who have 123 acres (50 hectares) in the Barbaresco area. The building is a tasting room on the main drag of Barbaresco, smaller than Barolo and slightly less touristy.

The advantage of Barbaresco is it’s what they call more “elegant,” meaning you can drink it earlier than Barolo although it is less full bodied.

“Generally you can feel more flavors, more flowers than in Barolo,” said Davide Rosso, who manned the tasting room. “It’s more easy to drink. Probably Barolo is a little more spicy.”

Of their 500,000 bottles a year, 40 percent are Barbaresco Classico, 40 percent come from nine single vineyards and 20 percent are Langhe Nebbiolo. I asked Davide if there’s a rivalry between Barolo and Barbaresco.

“Many years ago, maybe yes,” he said. “But not for the right reasons. Barbarescos reached their popularity in the ‘80s and ‘90s. Barolo has had famous wines since the unity of Italy. In the last decades, Barolo producers go to Barbaresco to buy Nebbiolo grapes to produce Barolo. Then many growers in Barbaresco believed that Barbaresco could be produced at the same high level as Barolo. Yes, there was a little rivalry.

“But today no.”

I tried the 2018 and 2017 Barbaresco Classicos, to taste the difference. Both have the taste of cherries and spicy notes such as white pepper and anice. The ‘17 was a little more spicy.

I bought the 2017 Barbaresco, a steal at €26. Like I said …

Fratelli Serio & Battista Borgogno, Via Crosia 12, Barolo, 39-01-73-56107, www.borgognoseriobattista.it, info@borgognoseriobattista.it, 9 a.m.-12:30 p.m. Monday-Friday, 2-6 p.m. Saturday-Sunday.

In 1897, a man named Cavalier Francesco Borgogno wanted to produce a wine for his wife’s small tavern in Barolo where he had founded the kindergarten. It’s 125 years later and Federica Bolla and cousin Emanuela Bolla represent the fifth generation running the winery.

In their tasting room not far from Damilano, Federica proudly showed me a bottle of Seriulin. It was the nickname for her grandfather, Serio Borgogno, the founder’s nephew who studied winemaking in France. The Seriulin is a blend of Nebbiolo and Dolcetto.

“We want to remember him,” she said. “When me and my cousin were children, he’d put in our water a drop of Dolcetto and Nebbiolo. Then he’d tell us in the Piedmont language, “Tasta si! (Taste this!)”

I tried their Dolcetto which is very fruity but not nearly as sweet as the name would suggest. They are also on Cannubi Hill and their 2014 and 2018 Cannubi Nebbiolos were excellent but totally different. The 2018 is fresher, fruitier. The 2014 is more spicy with a hint of licorice.

But the best wine I had all week, my most prized possession, is the 2016 Barolo Riserva. They only make a Riserva when they have a prize vintage. It’s aged five years instead of four and a minimum of 18 months in oak barrels.

It was so good I nearly wept. I don’t have the words to describe it so I’ll let Enotecadegustibus.com do it: “Red fruits and cherry, delicate herbaceous, spicy in the making, every time you bring the glass to the nose you feel a change, very balsamic with hints of cocoa and tobacco.”

I splurged and bought a bottle for €60. I came home with eight bottles: five Barolos, two Nebbiolos and a Barbaresco for about €250. As we drove home, our stash carefully stored in the trunk, I kept thinking of Serio Borgogno’s words when little Federica came up to give him a glass of Dolcetto or Nebbiolo.

“He’d say, ‘I don’t want Dolcetto! I don’t want Nebbiolo!’” she said. “‘I just want Barolo!’ Like an apple a day. You drink a glass a day of Barolo Cannubi wine.”

If you’re thinking of going …

How to get there: Drive. Public transportation in Le Langhe is nearly non-existent and only cars can reach the individual wineries. Call ahead to make sure they have space for wine tastings. Prices vary. Alba, Lange’s main town, is 35 miles (60 kilometers) from Turin and 90 (150) from Milan. Car rentals in Turin start at about €26 a day. From Milan they start at €23.

Where to stay: Poggio del Farinetti, Via Farinetti 24/25, Diano d’Alba, 39-338-465-8012, 39-360-103-8686, www.poggiodelfarinetti.com, info@poggiodelfarinetti.com. Located just north of Alba in a quiet hilly village, this B&B has rooms with spectacular panoramic views of the surrounding vineyards and the town castle. It also has a swimming pool and good buffet breakfast. It may be the nicest place I’ve stayed in Italy. I paid €385 for three nights.

Where to eat: Trattoria del Centro, Via Alba Cortemilia, Ricca, 39-01-736-12707, www.trattoriadelcentro.com, 11:30 a.m.-3:30 p.m., 7-11 p.m. Wednesday-Monday, 11:30 a.m.-3:30 p.m. Tuesday. A Piedmont specialty is risotto, Italy’s creamy rice dish. This simple eatery on the outskirts of Diano d’Alba had a Risotto del Dolcetto made from wine from its own cantina three miles away. It was one of the best risottos I’ve ever had. Mains start at €9.

Il Ritrovo dei Golosi, Via Bartu 3, Diano d’Alba, 39-01-316-2896, Il Ritrovo Dei Golosi – Ristorante, 5 p.m.-midnight Tuesday-Friday, 11 a.m.-midnight Saturday-Sunday. Down a short dirt road, the airy restaurant specializes in rich Piedmont cuisine. I had agnolotti ripieni di gorgonzola e ricotta saltate al pesto di noci (small ravioli filled with gorgonzola and ricotta cheeses and sprinkled with pesto and walnuts). The Langhe Dragon, a blend of Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc and Riesling, was worth the trip alone.

Bricco delle Viole, Via San Pietro 4, Barolo, 392-468-2169, noon-2 p.m., 7-10 p.m. Tuesday-Sunday. Sporting a giant wine barrel and corner walls made of old wine boxes, this artsy, 3-year-old restaurant adds an elegant twist to Piedmont cuisine. I had the ravioli del plin, agnoletti filled with meat and vegetables, for €17. Marco, the friendly waiter, emptied a bottle of Barolo in my €10 glass and gave me a tour of the wine storage room in back.

When to go: September and October. August is too hot and crowded. Global warming has moved the harvest season from mid-October to September and sometimes August. In September you’ll see vines full of grapes. Temperatures during our week in mid-October were perfect: sunny with lows in the 50s and highs in the high 60s.

For more information: Langhe Tourist Office, Piazza Risorgimento 2, Alba, 39-01-733-62562, Langhe Experience – Your Official Local Travel Advisor (langhe-experience.it), 9 a.m.-6 p.m. Monday-Friday, 9:30 a.m.-6:30 p.m. Saturday-Sunday.

October 18, 2022 @ 8:37 pm

Great article! Barolo is also my favorite wine. I was lucky enough to visit Le Langhe several years ago on a work trip. I was in absolute heaven, with the wine, the landscape, the food and the people. I still have several bottles stashed away from that trip. I am making note of your recommendations for lodging and restaurants for a future trip!

October 21, 2022 @ 6:52 am

Thanks for this very timely piece. Informative as usual. I’ll be in Le Langhe for four days on Sunday!

October 21, 2022 @ 4:33 pm

Thanks for this article recounting your trip to Le Langhe. I appreciate you providing specific such as tasting notes, producers’ names and addresses, restaurants, etc. I also enjoy skimming through your posts each week on “The Dog-Eared Passport” blog. BTW, Barolo is my favorite wine too! Salute!