Global warming and Italian wine: €2 billion loss and lower production of up to 30 percent has winemakers nervous

BAROLO, Italy – It’s late October and it’s still in the high 70s in Rome. Sea levels are rising to where scientists say Venice could be underwater in the future. Italy hit a record 120 degrees (48.8 celsius) in Sicily 14 months ago. Rain has steadily decreased and bottomed out last winter when Italy received a third less rain than normal.

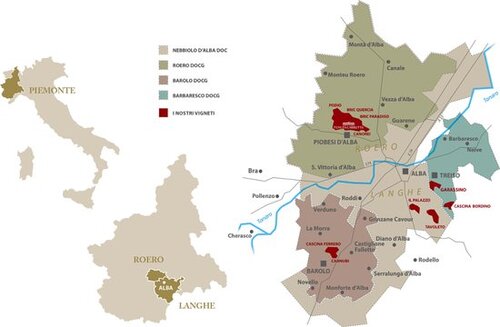

Global warming is alive and going frighteningly well in Italy where we’ve suffered through our worst drought in 70 years. In July Rome declared a state of emergency for five Northern Italian regions. I had a first-hand look at the problem two weeks ago when I visited the Piedmont region’s Le Langhe, the heart of Barolo country, my favorite wine in the world. I planned an October visit as that’s Italy’s traditional harvest season.

Not anymore. Global warming has flame broiled the vines to the point where grapes are quickly harvested as early as August. In my visit to four wineries, I saw very few grapes. What I did see was a lot of worry on the faces of winemakers.

“If it keeps going, we go over the top,” said Aldo Vacca, managing director of Produttori Barbaresco.

Translated, he means if global warming keeps its current trend, Italy’s wine quality will take a U-turn. That’s tragic. I don’t know about any of you, but forget how global warming causes killer floods and wildfires and the extinction of the polar bear.

DON’T TOUCH MY ITALIAN WINE!!!

Scary numbers

Mankind must make some major changes. Look at what climate change already has done to Italy’s wine industry:

- At the COP26 climate change summit in Glasgow, Scotland, in November 2021 it was reported that the Italian wine industry’s production, the largest in the world, dropped 9 percent that year.

- According to the International Organization of Vine and Wine, the Italian wine industry lost €2 billion in 2021.

- The four wineries I visited averaged a loss of production this year of 30 percent. Piedmont’s prized rice crop also lost 30 percent.

- According to the French National Institute of Agronomic Research, if average temperatures rise by 2 degrees celsius by 2050, as scientists predict, Italy would lose 68 percent of its vineyards.

Wineries are already in a defensive stance. Some in Italy have bought land in Spain’s Pyrenees Mountains, in Northern China and the South of England.

Some are shading vines with nets and removing leaves that collect excessive sunlight. They’re even spraying leaves with white clay that reduces photosynthesis and the temperature of the grapes and leaves.

At Aurelio Settimo winery in Barolo, Davide Boasso took me into his vineyards nearly void of grapes. They harvested in mid-September. Twenty years ago they harvested in mid-October.

He showed me a small shallow ditch that ran along the vine. They started doing that to preserve water from the little rain they did get.

“The soil was too dry,” he said. “The risk was the water would slip off the soil and not get absorbed.”

Global warming’s effects

The wine industry is fragile. Any change in even one season can devastate entire wineries. Now imagine how global warming can change the climate for generations and you know why the vines aren’t the only things around here standing on edge.

For a quick primer, here’s how climate change affects wine: When heat and photosynthesis is accelerated, it doesn’t allow the grapes enough time to properly ripen. It accelerates the sugar content in grapes and, thus, produces higher sugar levels and higher alcohol content. Over the last 30 years, alcohol content in Italian wines has already increased by 1 percent. Italians frown on wine with high alcohol.

Making matters worse, hotter nights don’t allow vines to absorb soil nutrients and they wind up producing less acidic and flavorful fruits.

As winemaker and oncologist Francesco Bordini told Vinepair.com, “If you want to understand if it will be a good or bad vintage, check if during the summer there were warm nights.”

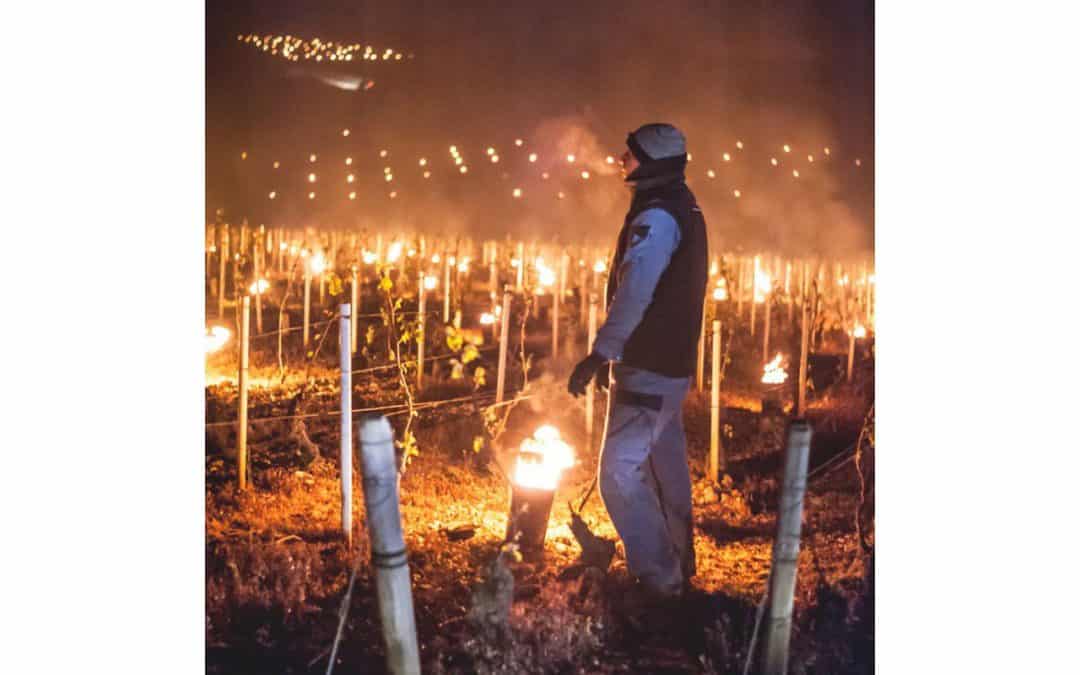

The warm weather also produces very delicate early buds that are susceptible to frost damage. Le Langhe’s Piedmont region in the foothills of the Alps is known for spring frosts. Bordini says this is the “most dangerous effect” of global warming.

One freezing night in the summer of 2021, Tenuto di Trinoro winery in Tuscany had to light 3,500 candles to keep the buds from freezing. Then when the blistering heat came that summer, they had to expedite the harvest to avoid a wine that would be too sugary and alcoholic.

“When you see the problem, it’s too late,” Tenuta di Trinoro winemaker Benjamin Franchetti told Vinepair. “The issue for us now is being able to foresee it.”

Increased heat can also affect the taste. Tannins, the essential ingredient in how a wine tastes, becomes much stronger as the fruit has less time to ripen and less time to increase the quality of the tannin.

Some wineries have put hundreds of miles of plastic irrigation piping beneath the soil to release water underground closer to the roots.

For the first time in 30 years some wineries in the Central Italy region of Emilia-Romagna have turned away from white Chardonnay, which needs cooler temperatures, and growing more native grapes such as Albana.

“I think soon, it will not be possible to cultivate Chardonnay anywhere in Italy,” Bordini said.

Le Langhe wineries concerns

Tiziana Boasso has run Aurelio Settimo for 15 years. It’s been in her family since 1943. She remembers back in 1971 when they finished the harvest on Nov. 1 “almost under the snow,” she said.

In a way she’s lucky. Global warming doesn’t affect the vineyards in Northern Itraly as much as Central and Southern Italy. Still, this August Le Langhe, just a short drive from the Alps, hit 108 degrees (42 celsius).

“I’m worried, surely, as a lot of my colleagues,” Tiziana said.

They were so desperate for water, she had the farmer on speed dial to prepare the little trench and hoard water.

“I was a witch in July,” she said. “I had a round ball and looking for the forecast and when I saw in a week there was a forecast for three storms, I called the man in the tractor and told him now it is the moment.”

So far, global warming hasn’t affected the taste of Barolo, Nebbiolo or Barbaresco in Le Langhe.

“I think it’s really big for the next year because in the summer in June, July and August was really, really hot,” said Davide Rosso, tasting room manager of Produttori Barbaresco, “Too hot. We have no rains and so Nebbiolo does not suffer too much but in other years? Yes. Probably in two, three, four years we’ll see the results of this change.”

Some wineries are adapting to climate change by assuming their wine will change some.

“We don’t sell like Coca-Cola that needs to be the same every year,” said Federica Boffa of Serio & Battista Borgogno in Barolo. “Of course, climate change we feel a lot also here in the last few years. The climate changed a lot.

“But I think the right way to go is adapt our work to that climate. In the past, for example, we cleaned the grapes from the leaves in the summertime. Now the grapes are a little bit more covered just to protect, like an umbrella.”

The view elsewhere

Back in Rome on Sunday I attended Life of Wine, the annual wine tasting event that brings wineries from Calabria to Val d’Aosta, on the Swiss border. I wanted to hear about global warming’s impact on wineries in warmer climates.

Enrico Cerulli runs Cerulli Spinozzi in Abruzzo, east of Rome’s Lazio region and bordering the Adriatic Sea. He said the last few years he’s had no rain from spring to the end of summer. His production has dropped 20-30 percent.

“It’s not about the taste,” he said. “The quality of the wine is still very good. It’s more terrible in terms of concentration. For example, we make our rose with the same grape we use to make the red and in the last few years the color and intensity of the rose is getting darker and darker.”

He said every year he harvests earlier. This year he started in the middle of August with the whites and beginning of September with the reds.

“The fear we have every year is that with so much heat and no rain, the vine could stop producing,” he said.

To combat it, he already planted a small vineyard of Pecorino at 800 meters, as a test.

Ludovica Borgna of Ventolaio in Tuscany, famous for its Montepulciano, said her biggest fear is they will be forced to use different kinds of grapes.

“But it’s not easy because Montepulciano is made from Sangiovese grapes,” she said. “We can’t change it. If you change our philosophy you will change our history. For us, that is not possible.”

Adriana Burkard of Arillo in Terrabianca in Radda in Chianti, Tuscany, said they’re planting a new clone of grapes that are more resistant to climate change. Two years ago the winery started the 360° sustainability program which is organically converting their estates and maximizing water resources with the use of solar panels and the completion of a natural capital analysis called a Life Cycle Assessment.

“We are re-establishing biodiversity in the fields,” she said. “We have a lot of forest so we want to compensate our production of CO2 with our forest.”

I asked what she says to people who don’t believe in climate change.

“That they should come and see the effect on the plants and on the grapes,” she said. “They should come and touch it. There is absolutely a big change.”