Montenegro hiking: Solo strolls to sea vistas and tombs

(This is the last of a three-part blog on Montenegro.)

LOVCEN NATIONAL PARK, Montenegro – The wild-eyed taxi driver with as many treads on his face as on his tires sped up the mountain like he was escaping Tito’s secret police. He had picked me up in Cetinje, Montenegro’s original capital which still holds mystical reverence in the country.

He pointed up toward a mountaintop we couldn’t yet see. He said, “Njegos!” and clenched his fist and flexed his skinny right arm. Yes. Njegos. Peter II Petrovic Njegos. Strong. I didn’t need to know Montenegrin to understand that the father of Montenegro is still a hero around here.

That’s why I wanted to climb a mountain to visit his tomb.

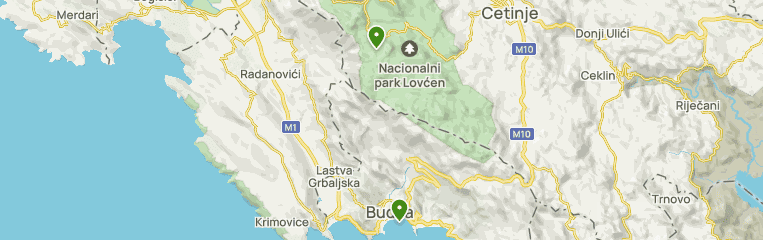

Njegos wasn’t my biggest lure. He was just the ornament at the top of one of Montenegro’s bigger attractions: hiking. This former Yugoslavian republic is the size of Puerto Rico yet has five national parks. Three of them were established in 1952 after Yugoslavia had settled into what would be a half century of communism.

I went white-water rafting in Durmitor National Park the day before. Biogradska Gora National Park in the northeast features one of the most untouched forests in Europe. The other is Lovcen National Park, where the cabby whisked me up to experience some of the best hiking in the Balkans.

The arrival

He had found me in a small diner near Cetinje’s bus station. I had ordered a traditional Montenegrin dish called cevapi. It’s basically Montenegrin sausage. I just wanted a little snack. For only €5, I figured I’d eat quickly and head up the mountain.

Out came a dish the size of a catcher’s mitt holding a pile of 10 sausages with a big dollop of kajmak, a sweet sauce made from cooked milk. I ate about six before I waved the white flag and wondered why more Montenegrins aren’t the size of davenports. I know Bengal tigers that couldn’t finish Montenegrin dishes.

The taxi drove me up through a forest of black beech trees. When they lose their leaves later in fall, they are nothing but black tree trunks. It’s why the ruling Venetians in the 17th century called this area “Montenegro,” or “Black Mountain” in Italian.

The forest changed to munika, a spiky pine tree that survived the Ice Age, and I realized this may be the most unspoiled national park I’ve ever seen. In a 15-minute drive we didn’t see a single structure. Finally, after eight miles (14 kilometers) we came across a tall, A-frame building fronted by huge glass windows. My Hotel Monte Rosa, built just 10 years ago, is a four-star ski lodge in winter and a hiking base in summer.

It has an indoor pool, a Jacuzzi and a large front patio where you can sip Niksicko beer and Montenegro’s underrated wines while staring up at the peaks you’re about to climb. With my ice-cold Niksicko, I stared up and saw Njegos’ tomb, a sandstone structure atop a massive rock, 7.5 kilometers away and 5,436 feet (1,657 meters) in the air.

The climb to the tomb attracts thousands of tourists a year. I first wanted to walk in solitude. The next morning, I went to the little wooden tourist information center where a tall, mustachioed man in his 30s broke out a map bigger than his desk. He recommended a hike to Babina Glava, a seven-mile (13-kilometer) round-trip hike. He assured me I would not be disappointed with the views.

Solitude? I didn’t see another person for two hours.

Babina Glava

The trailhead started at the side of one of only three hotels I saw during my three days in the national park. After 10 minutes the pavement turned into gravel and rocks under a forest of pine trees blocking out the sun on a perfect hiking day in the low 60s.

I reached one fork in the road with no directional arrows. Not wanting to wander aimlessly all morning, I called the hotel desk whose conscientious clerk who had hiked it couldn’t help. I walked 100 meters to the left and ran into a dead end at the forest. I reversed paths and continued uphill, losing only about 20 minutes.

It’s an easy hike. It’s not steep and not hot. Sun broke through in slivers like light rain through the pine tree canopy. And the terrain is beautiful. Lovcen National Park is home to 1,300 plant species, including many endemic to the Balkans such as certain orchids, tulips and a purple plant called Nikola’s knapweed.

I hiked in near complete silence. I saw no other hiker. I heard some of the 200 species of birds somewhere above the trees. Maybe I missed the falcons and eagles I read often hover in these mountains.

When I got above the treeline after less than two hours, my reward was a spectular view of the sea and Kotor Bay, Monteverde’s iconic view and one of the prettiest in Europe. The triangular bay was lined with the red-tile roofs of villages with the Adriatic Sea beyond. At 4,836 feet (1,474 meters), even under cloud cover, I could see Njegos’ tomb. I was almost at eye level.

On the way down, I met a total of six couples trudging up. “The view is worth it,” I repeated to each one. I was back at the hotel with my celebratory Nicsicko by 1 p.m. I had gone 13 kilometers (or 6,405 steps on my cellphone) in about three hours. This was my warm up.

Montenegro’s No. 1 hike was the next day.

Montenegro’s father

Read about Njegos and he comes across as a matinee idol with a Bible in one hand and a sword in the other. Peter II Petrovic Njegos (1813-1851) was born into one of the area’s most powerful trbies in the mountain village of Njegusi outside Cetinje. Educated in Serbian monasteries, he became a prince bishop but also a poet and philosopher.

After the death of his ruling uncle, Peter I, Njegos became Montenegro’s spiritual and political leader. He united Montenegro’s tribes, established a central state and developed a tax system to finance the backward, poor country.

While the taxes led to numerous revolts, he led a crucial victory over the ruling Ottoman Empire and sought to expand Montenegro’s territory. His policies are believed to have helped lead to what became modern Yugoslavia.

His tomb, built from 1970-74, glowed above me, a sandstone grave that has united the country.

Njegos’ Tomb

It’s 3 miles (5.5 kilometers) to the tomb atop Jezerski Vrgh, at 5,436 feet (1,657 meters) the second-highest peak in the national park. On a 60-degree morning I trudged up a dirt road toward a backdrop of green and white mountains in the distance.

Climbing to see a tomb felt like seeking a monument to George Washington in the middle of the Rocky Mountains. This was almost as steep as some of the trails I’ve hiked in Colorado. After crossing a narrow road, which snakes up the mountain carrying masses of lazy tourists, I entered a forest. The steep trail was void of other hikers. I saw stone ruins and a tin storage shed covered in graffiti.

The climb wasn’t nearly as scenic and my sweat and heavy breathing confirmed its moderate difficulty. When I emerged from the forest, I saw a large parking lot with a small souvenir stand where a man was stacking rakija bottles and traditional caps on a display stand.

Next to him was a steep set of stairs that led to a modern, concrete walkway. It’s 461 steps to the entrance where I finally saw other members of humanity. Tourists dressed way too well for hiking sat at a crowded outdoor snack bar eating ice cream, drinking beer and staring at the view below. Droves of tourists hauled up the steps after getting dropped off by giant tour buses.

Walking through the dark, tunnel entrance, I came across two giant black granite statues. An eager security guard told me they represented Njegos’ brother and sister, although they were indistinguishable.

Behind the statues is Njegos himself, enveloped in the wings of an eagle, carved from a giant block of black granite. His tomb is below. The only path available is out the back where a circular viewing platform offers a jaw-dropping panoramic view of the countryside.

I couldn’t see the sea from there but I could see an endless string of craggy, stone mountains trimmed with green trees. Emerald green meadows ran between the red-tile roofs of villages. On the other side I could see my hotel, looking as small as a crude, mountain shelter.

When I returned to the hotel, a wedding reception had commandeered the patio. The bride and groom fed each other cake. The guests danced to traditional Montenegrin songs, a mix of folk music and European rock.

The tomb sits at 1,657 meters.Ol’ Njegos would be proud of what his country gave him and what it has become after him. Totally unspoiled. Savagely beautiful. Fiercely independent.

And the bride swung a tiny young girl in a makeshift waltz. Both tipped their heads back and laughed.

If you’re thinking of going …

How to get there: Buses leave the capital of Podgorica for Cetinje about every half hour. The 45-minute trip is €3. Taxi from Cetinje bus station to national park is €15.

Where to stay: Hotel Monte Rosa, 382-89-300-600. Modern, four-star hotel with Jacuzzi, indoor pool and excellent restaurant. Very helpful staff. They even took a swimsuit I left in the room to my hotel in Podgorica. For three nights, including meals and drinks, I paid €193.40 including breakfast although Booking.com lists three nights in October at €338.

Where to eat: Hotel Monte Rosa. There are very few restaurants in the national park. Stick to Monte Rosa. It has a huge menu, including traditional Montenegrin dishes such as Podgorica popeci (meat rolls stuffed with prosciutto and cheese) and a massive mixed meat platter. Mains start at €12.50.

When to go: Avoid July and August. It’s hot and the tomb is crowded from bus tours. The park is 10 degrees cooler than on the coast. During my three days in September it never got over 70 degrees. Nights were in the low 50s. There is skiing in winter.

For more information: Lovcen National Park Visitor Centre. It’s a small building about a 10-minute walk up from Hotel Monte Rosa. They have maps and advice for hiking all over the area.