Turkmenistan: Hello from “The Weirdest Country in the World”

(This is the first of a three-part series on Turkmenistan.)

ASHGABAT, Turkmenistan – I’m sitting in an enclosed gondola car 75 meters above one of the most isolated countries on Earth.The nation of Turkmenistan boasts that I’m riding what is in the Guinness Book of World Records as the Largest Indoor Ferris Wheel in the World.

That shouldn’t be confused with its other claims such as the World’s Largest Building in the Shape of a Bird, the Largest Hand-Woven Carpet and the Largest Number of Fountain Pools.

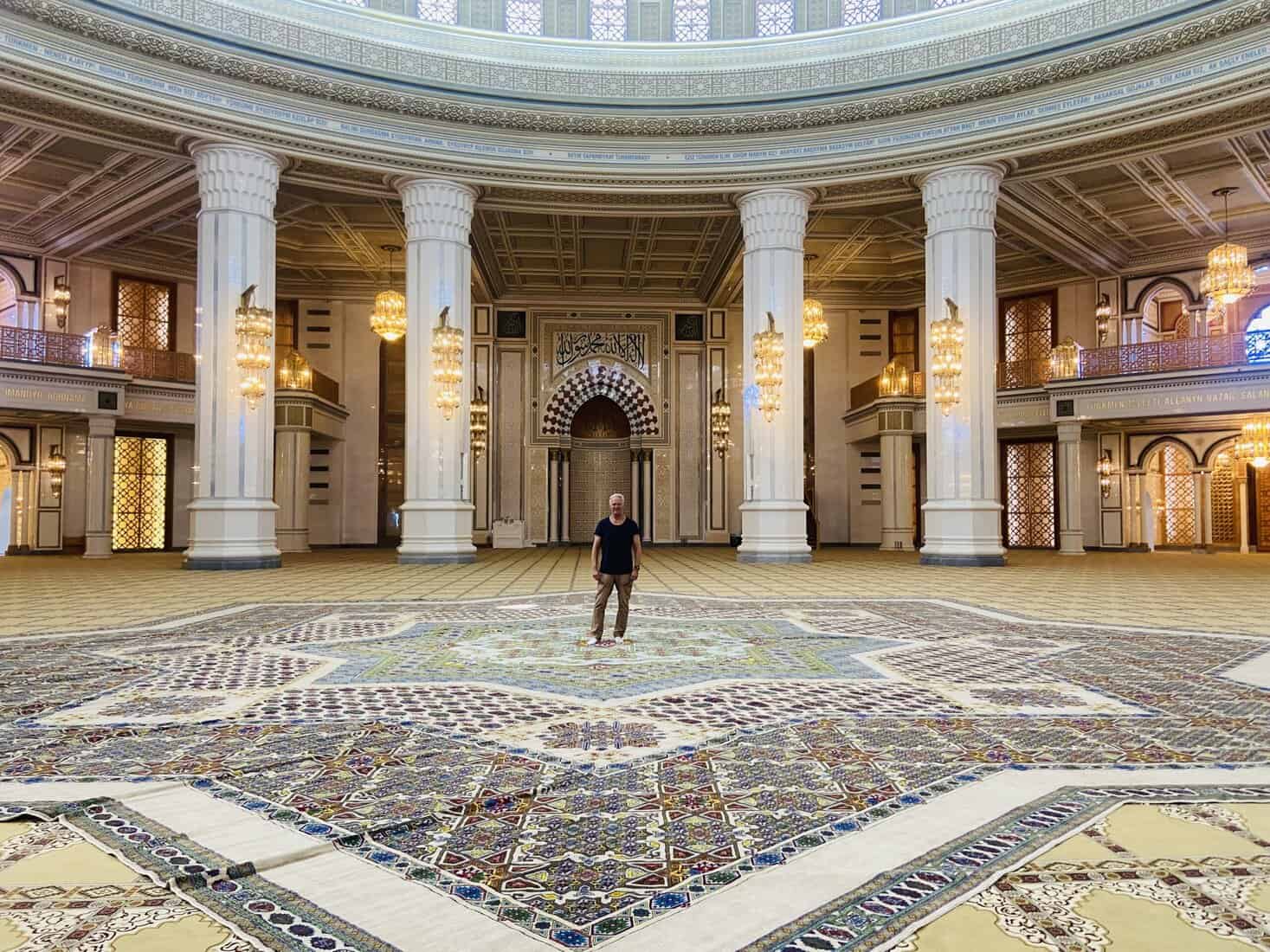

They could add another but the Guinness Book of World Records doesn’t have a category for the World’s Largest Mosque That No One Prays In.

Looking down from above, I notice one of the nation’s many dichotomies, tied, of course, to said Guinness Book of World Records. The capital of Ashgabat is in the book for the World’s Largest Concentration of White Marble Buildings.

They total 543 and are scattered around half the city like giant pearls on a sandy beach. Gargantuan palaces, skyscraping towers, huge apartment complexes, all blindingly white from the sun that shines nearly year round. At night, some sport neon lights of changing colors like giant casinos.

But as I gaze down at this architectural wonderland, I see something missing. Traffic. As in … nothing. No cars. No bikes. Hell, no people. The spotless six-lane boulevards lacing through this part of the city of 900,000 people are practically empty. Every few minutes, a lone car passes. I look at my watch.

It’s Friday at 10 a.m.

Why? Because in Turkmenistan’s quest to stand out to the world with white marble palaces and giant landmarks, financed by the fourth-largest gas reserves in the world, it forgot something to build around them – such as businesses, markets, bars, restaurants, services.

There is no traffic on this side of town because there is no reason to go except to see the monuments or go home. What would you expect from a country where they fine people for dirty cars and it has a national holiday for melons?

Welcome to Turkmenistan, the Weirdest Country in the World – and the most fascinating country I’ve ever visited.

Why Turkmenistan?

I’d been intrigued with this former Soviet republic ever since 2019 when I spent three weeks touring the other four Stans. In Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, I’d ask about Turkmenistan and locals would roll their eyes. Some would smirk.

Let’s see. Independent travel isn’t allowed. Social media apps are blocked. So is free speech. Its former dictator outlawed black cars and facial hair on anyone under 70. I kept thinking one thing:

My kind of country, my friend! My kind of country!

What I learned is that it may be the cheapest country I’ve experienced (thanks to a barely disguised black market). The food is terrific, the beer is cold, crime is nearly non-existent, the people are friendly and, with little traffic and a plethora of clean cars, it’s easy to get around.

But to visit Turkmenistan, one must go on an organized tour and only after receiving a Letter of Invitation from the government. I chose Saiga Tours which specializes in Central Asia (a saiga is an antelope indigenous to the region). Formed in 2021, it is likely the world authority on Turkmenistan.

Two of our four guides, Australians Eilidh Crowley and Ben Johnson, who own Saiga along with Eilidh’s Aussie husband, Ben Crowley, have all been to Turkmenistan more than 60 times each.

Saiga took care of paperwork that would turn Rick Steves into a couch potato. Complicating matters is credit cards are as useful in Turkmenistan as Cambodian riel. Cards are not accepted. They only accept cash and you have a better chance of hitting 35 black on a roulette wheel than getting money from the few cash machines.

Dollars are the preferred currency. I went to my bank in Rome and stuffed my bulging money belt with enough dollars in small bills to last me nine days, including medical and transport emergencies.

I fly to Turkmenistan feeling like a drug dealer.

But getting through immigration is half the battle. Flying via Istanbul, I land at 2 a.m. at Ashgabat International, which, indeed, is shaped like a giant bird with wings and a bird’s head spanning the entire facade. It is also, indeed, sparkling white marble.

Armed with my prized Letter of Invitation and nearly as much money as the average Turkmen makes in a year, I do the Turkmenistan arrival dance: Stand in line at the visa desk to give my passport, stand in line at the bank desk to pay $14 for the visa and $31 for a Covid test they never administer and return to the visa desk to get my passport with a pretty green visa stamp.

I feel honored. Turkmenistan, a country of 7.5 million people, is 80 percent desert and one of the least-visited countries in the world. Ashgabat has fewer than 30 hotels. The government does not release official numbers but it’s believed it gets only about 6,000 visitors a year. In fact, each visitor is given a number when he arrives.

On my Entry Travel Pass, with three months left in 2025, I am No. 4,430.

A Saiga shuttle drops me and a few others at our hotel. The Ak Altyn Hotel is in the old Soviet part of town where tenement buildings feature peeling paint, cracked bricks and barred windows. But on the scruffy grounds between the buildings I see what I’d see the entire week in Ashgabat.

Shiny white Lexuses.

Post-Soviet history

The Al Altyn was built in 1994. Three years earlier, Turkmenistan gained independence after the fall of the Soviet Union and our hotel lobby walls are adorned with pictures of the former dictator whose fingerprints are around the country to this day.

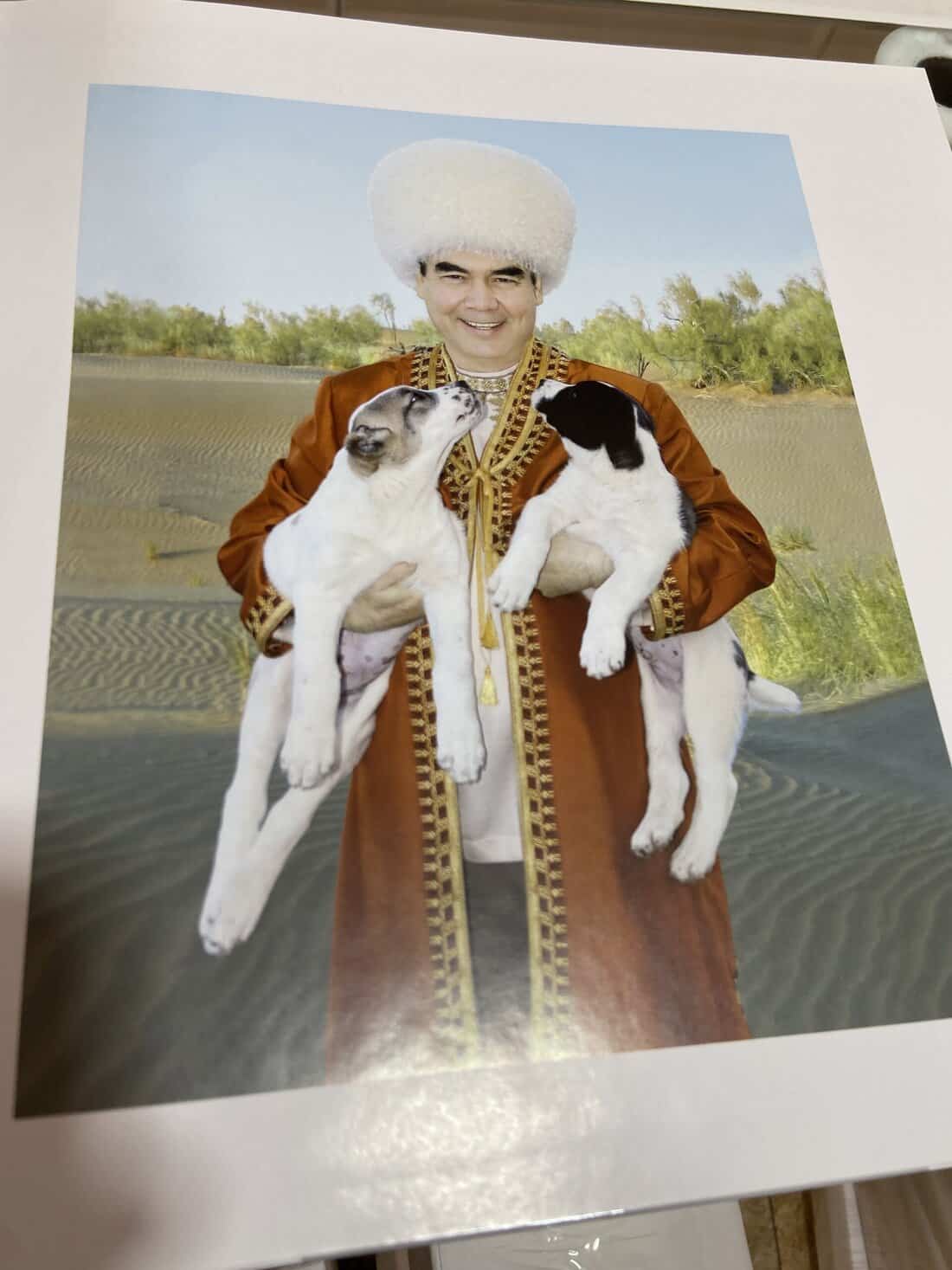

There is Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov riding one of Turkmenistan’s famed Akhal-Teke horses. There is Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov holding his beloved Alabays, Turkmenistan’s prized shepherd dogs. There is Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov smiling in the countryside wearing Turkmenistan’s trademark white, furry Cossack hat which looks like it doubles as his dogs’ overstuffed bed.

He gave himself the nickname Arkadag, Turkmen for “protector” which appeals to his massive ego, not to mention foreign headline writers. He ruled from 2006-2022 and his lavish spending transcended international borders. He spent $5 billion on an Olympic stadium complex for the 2017 Asian Indoor and Martial Arts Games and the stadium remains empty.

In 2019, he spent $5 billion to build a new city on a desolate plain 20 miles north of Ashgabat. He called it, of course, Arkadag. In 2023, he formed Arkadag FC, a new soccer team in Turkmenistan’s first division. He immediately bought 14 of the 26 players on the national team, extending the signing window so he could land them, and the team went 24-0-0 in its first season, outscoring opponents, 83-17. This season it is 21-0-0.

In 2015 he built a gold statue of himself upon a horse atop a 65-foot-high marble pedestal in the middle of a roundabout.

His son, the current president, still blocks all Western social media apps. I could not access WhatsApp, Facebook, Instagram or X. The Al Altyn was the only place in Turkmenistan I could read and send email although some in our group frequented one modern cafe with full Internet.

Turkmen stream using a cottage VPN industry provided by surrounding countries.

Visitors are not allowed into Turkmen homes, and Turkmen are not allowed in visitors’ hotel rooms. Turkmenistan did not report a single case of Covid. Arkady set an 11 p.m. curfew.

And to think Arkady was Turkmenistan’s voice of reason.

Reign of Turkmenbashi

Arkady, a former dentist and deputy cabinet chairman, replaced Saparmurat Niyazov, an old Soviet hand who bridged the transition from communism to independence. Calling himself Turkmenbashi, which means “Leader of the Turkmen” and using it to rename the port city of Krasnovodsk (notice a trend?), he survived an assassin’s bullet in 2002 but not a heart attack in 2006.

When Arkady took office – winning, ahem, 89 percent of the vote – he removed some of Turkmenbashi’s startling laws that helped give his country its label as planet Earth’s weird uncle:

- Black cars were outlawed as Turkmenbashi felt the color was unlucky. Still, during my week I saw nothing but white cars in Ashgabat with an occasional silver or beige. “You can have black cars,” said Ben Johnson, our guide, “but you’re a prize target for policemen to collect their lunch money.”

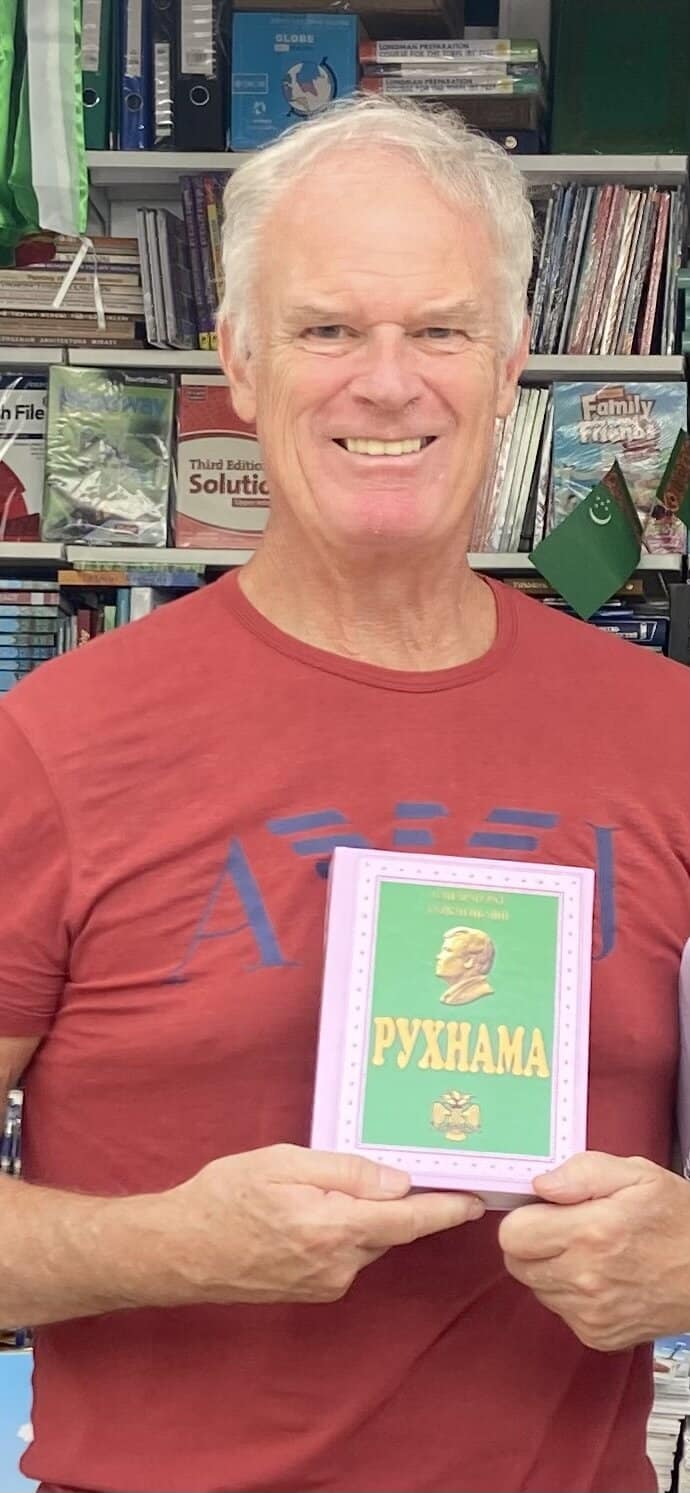

- His semi-autobiography from 2006, Ruhnama, was mandatory reading to acquire a driver’s license and mandatory in all public schools and mosques. Turkmenbashi said God told him anyone who read his book would go straight to heaven.

- He renamed all the days and months after family members.

- In 2004 he spent $100 million on the Turkmenbashi Mosque and Mausoleum. The mausoleum was built to house his body and his family’s, three of whom were killed in a 1948 earthquake that destroyed 83 percent of Ashgabat. The mosque can hold 10,000 worshippers which is 10,000 more than ever go there to pray. Turkmenistan is 96 percent Muslim but few practice. In nine days in Turkmenistan, I hear a iman’s faint call to prayer only once, a leftover from the atheist days of the USSR.

- Turkmenbashi banned smoking as he was trying to quit.

- He banned women TV anchors from wearing makeup on air.

In 2022, Arkady stepped aside to give the office to Serdar who, unsurprisingly, won 73 percent of the vote. He has changed little including his predecessors’ long-standing iron-fisted control over free speech, another holdover from the Soviet days. Reporters Without Borders has ranked Turkmenistan second to last in its press freedom index, ahead of only North Korea.

I read reports that one out of every three in Turkmenistan is an informant. Said Ben, “If someone doesn’t rat, another person may rat on that.”

Ashgabat has been called “A spooky Las Vegas” and a “cross between Las Vegas and Pyongyang.” It is with this backdrop that I took my first steps in exploring The Weirdest Country in the World.

Ashgabat

Before independence, Turkmenistan’s biggest tourist attraction was a hole in the ground.

In the late 1960s, in the desert 165 miles (274 kilometers) north of Ashgabat, a giant sinkhole exposed leaking gas that killed a local shepherd. Soviet scientists swooped in and started various fires in the hole hoping it would suppress the gas.

They did but the fires remain. For 60 years, those fires have turned the hole, known as the Darvaza Gas Crater, into a giant fireball and earned an appropriate nickname.

The Gates of Hell. (I will blog about it Tuesday.)

Today, Turkmenistan is known for one of the largest collections of beautiful monuments in the world, all built or redone after independence. While the country may never fully embrace the Internet, it may make the cover of Architectural Digest.

On a gorgeous late September sunny day in the low 80s, dry with a cool breeze coming down from the surrounding Kopet Dag mountains, 32 of us follow Saiga guides on a monumental monument crawl.

Our first stop is the famed Ferris wheel, known as the Wheel of Enlightenment. It was built in 2011 for Turkmenbashi who has his own gondola complete with cup holder, computer and Turkmenistan star symbol emblazoned on the side.

Down below is a four-lane bowling alley, an arcade room, kiddy rides and a climbing wall. Only one problem.

Turkmenbashi has never visited.

Too bad. When my car stops at the top, I see one of the most magnificent views in the country. It’s a vast desert sprinkled with giant white baubles. And of course, I had to search the horizon for a car.

“Do you feel enlightened?” Ben says as we leave.

We go to the Monument to the Constitution, a snow-white tower stretching 607 feet (185 meters) into the sky topped with a gold needle and lined with Turkmenistan’s symbolic five stars you see everywhere. They represent the country’s five provinces and five tribes.

Then comes another needle. Independence Monument is a javelin-shaped tower built exactly 91 meters (300 feet) high to symbolize the year of independence. Two stern soldiers in white dress shirts and blue ties guard the tower, joining a giant statue of turbaned Oguz Han, the founder of the Turkmen people, menacingly holding a bow and quiver of arrows.

Nearby stands a statue of Turkmenbashi himself, holding his coat over his shoulder like a Roman emperor.

We walk through the Palace of Happiness, a very weird giant wedding shrine. Atop a four-story building of mismatched floors stands a giant gold ball inside Turkmenistan’s symbolic star. I can’t help thinking the ball symbolizes a man’s testicle trapped inside a box, but I say nothing.

As we leave we see a wedding procession of a bride and groom standing on the side of a huge boulevard, posing for photos with monuments and vast desert as a romantic backdrop.

“Don’t do it!” yells a man in our group. His words fall short. Few Turkmen speak English.

In a monument dash, we go through the Memorial Complex, a vast statue-laden square dedicated to the 1948 earthquake victims; the Argadat Memorial, one of two statues of him in town; and Lenin Park, a statue of Soviet Union-founder Vladimir Lenin, that was, ironically, one of the few structures that survived the earthquake (fill in your own one-liner).

Finally, we climb 228 steps to a 20-meter platform holding a 60-meter statue of Magtymguly Pyragy, Turkmenistan’s famed 18th-century poet, holding a book the size of a small parking lot.

But the most remarkable structure was one that stood out for its vast emptiness in a country famous for it.

A mosque.

Turkmenbashi Ruhy Mosque

Turkmenistan is my 22nd Muslim country. I’ve seen too many mosques to count. But Turkmenbashi’s is the, um, weirdest I’ve ever seen. Turkmenbashi built it in 2004 along with an adjacent mausoleum to hold his family’s bodies.

But Sunnis, a major Islamic sect, believe mosques are for worshipping God, not people. Islamic leaders in Saudi Arabia were hysterical. Turkmenbashi didn’t care. After all, in 1995 the United Nations officially recognized Turkmenistan’s claim of “permanent neutrality.”

The Saudis can go pound sand.

The beautiful white marble mausoleum and gold dome has a viewing platform above five coffins: Turkmenbashi’s is inside the Turkmen star and surrounded by his father, who was killed in 1943 in the Caucasus during World War II and two siblings and his mother killed in the earthquake, one that Turkmenbashi amazingly survived.

Above it all is a statue of his heroic mother dragging little Turkmenbashi from the rubble.

Next door is the mosque nearly identical in design but much larger with four towering minarets. We walk inside to a cavernous prayer room the size of a football stadium. Lining the floor is a rug spanning 21 meters x 13 meters containing 400,000 knots per meter and emblazoned with the giant Turkmen star.

In a room that holds 10,000 people, we tourists spanning nations from the U.S. to China are the only ones here.

Islam holds an odd place in Turkmenistan. Under communism, Turkmenistan had only four mosques. More have been built but few Muslims pray. They do not practice Ramadan. Except for our van driver rolling out a mat on the side of a road and praying during a snack break, I see nothing resembling an Islamic state.

I see no women wearing burqas. Instead, they all wear ankle-length gowns with colors representing their school level and job status. Ashgabat has an active dating scene.

It’s all a symbol of Turkmenistan’s neutrality. Turkmenbashi and Arkady saw nearby Tajikistan and Uzbekistan get radicalized. Turkmenistan is sandwiched between the powder kegs of Afghanistan and Iran. The country wanted to keep Islam under control.

So why then did Turkmenbashi build a mosque?

“You ask too many ‘Why?’ questions, John,” Eilidh scolds me. “The answer is, ‘It’s Turkmenistan.’”

A Turkmen’s view

Interviews are difficult in Turkmenistan. The country has a State Committee of Tourism folded into the Ministry of Culture. Local tour agencies and hotels refer all questions to the government which did not return email requests.

I have so many questions. Why does Turkmenistan rely solely on its gas reserves and not try to diversify its economy with tourism as Saudi Arabia has done? Where do you draw the line on allowing tour groups in while preserving the local culture?

Did the unemployment rate really drop from 25 percent, as the New York Times reported in 2003, to under 5 percent? Do banktellers really only make $36 a month?

The country has experienced the exodus of many youths. One bartender tells me just before closing, “I’m OK but I don’t have a decent job. I have an interview with another and I’m studying English.” Studies list Turkmenistan only above Kyrgyzstan for the best quality of life among the five Stans.

But most locals do seem happy and poverty is at a minimum. I see no homeless people or beggars. Turkmen receive 200 liters of free gas a month. Of course, you can buy 40 liters of gas in Turkmenistan for about $1.

One of our guides is a Turkmen. Serdar Varlamov is a burly 49-year-old who could pass for a former Turkmenistan weightlifter. Instead, he has been one of the country’s few native tour guides for the past 15 years.

In the remote village of Nokhur, 150 kilometers (80 miles) northwest of Ashgabat, we’re standing above a weird graveyard where the gravestones are covered with ram horns, ancient Turkmen symbols of strength.

I ask him why Turkmenistan is so down on tourism.

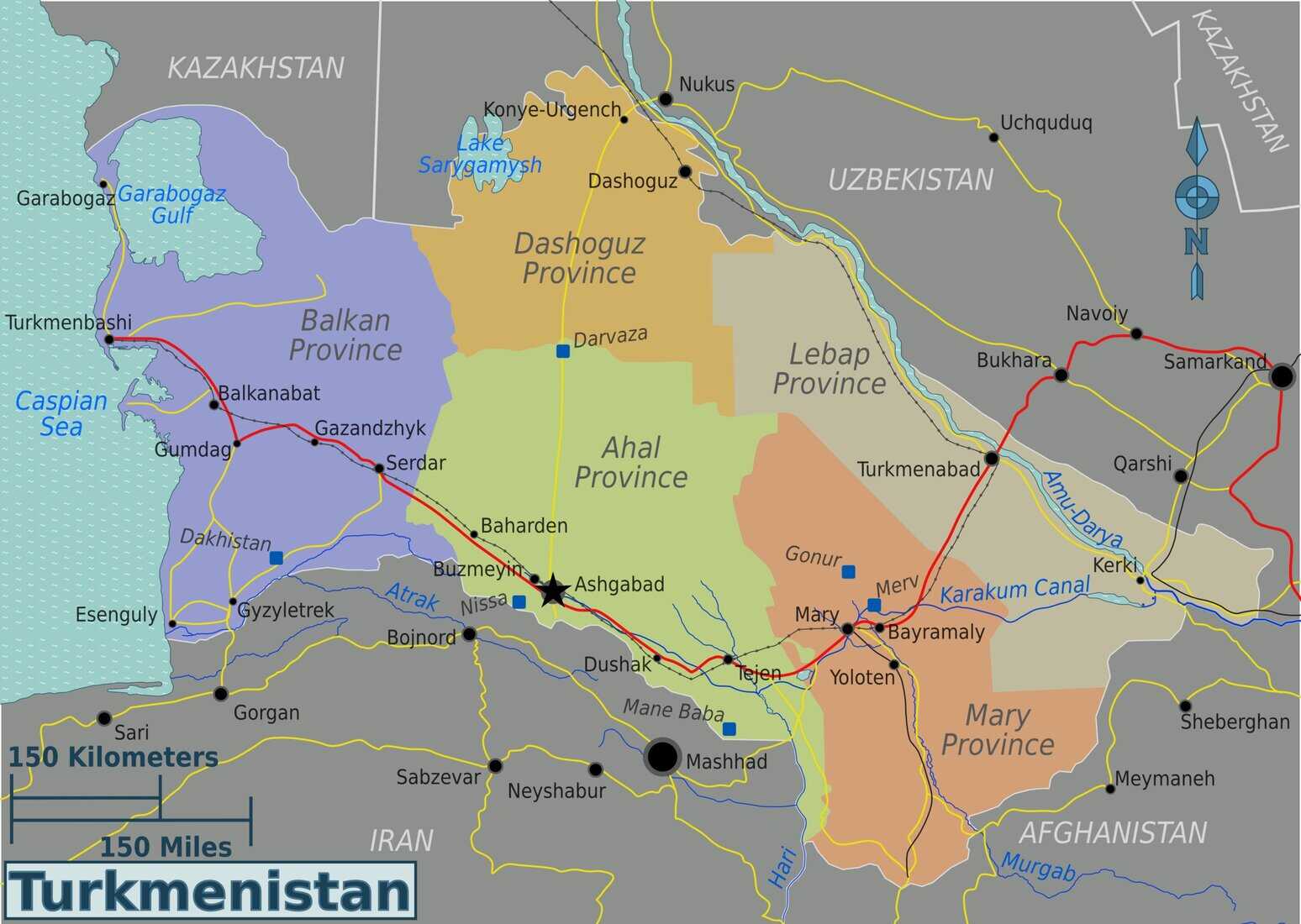

°Imagine the map,° he says. “The territory of Turkmenistan is 500,000 square kilometers. But the desert is 400,000 square kilometers. That’s 80 percent. People are living just around the desert. The areas around the desert are border zones. Everywhere you will go you get into border zones.

“Because behind these mountains is Iran. And the border zone. Maybe you are a spy. Maybe you’re working for Iranians.”

He said his country is not equipped to handle more than the 6,000 tourists it gets annually now.

°Our infrastructure isn’t developed enough to handle more tourists,” he says. “Hotels, transportation, guides. How do we invite 100,000 tourists if we have no place to put them?”

I tell him about the tourism disasters I’ve seen elsewhere. The last time I was in Phuket, Thailand, it had so many German tourists, it had bratwurst shops on the beach.

°You know what happened in Thailand, Turkey, Indonesia,” he says. “They’re surviving on just tourism, not because of their resources. Turkmenistan has the fourth-most natural gas in the world. We’re sixth most in exports. We have enough money to cover buildings with white marble.”

But Saudi Arabia has more money than Turkmenistan, I say, and they’re diversifying through tourism.

°We don’t need more money,” he says with a broad smile. “When the gas is finished, we will develop tourism and make the same money.°

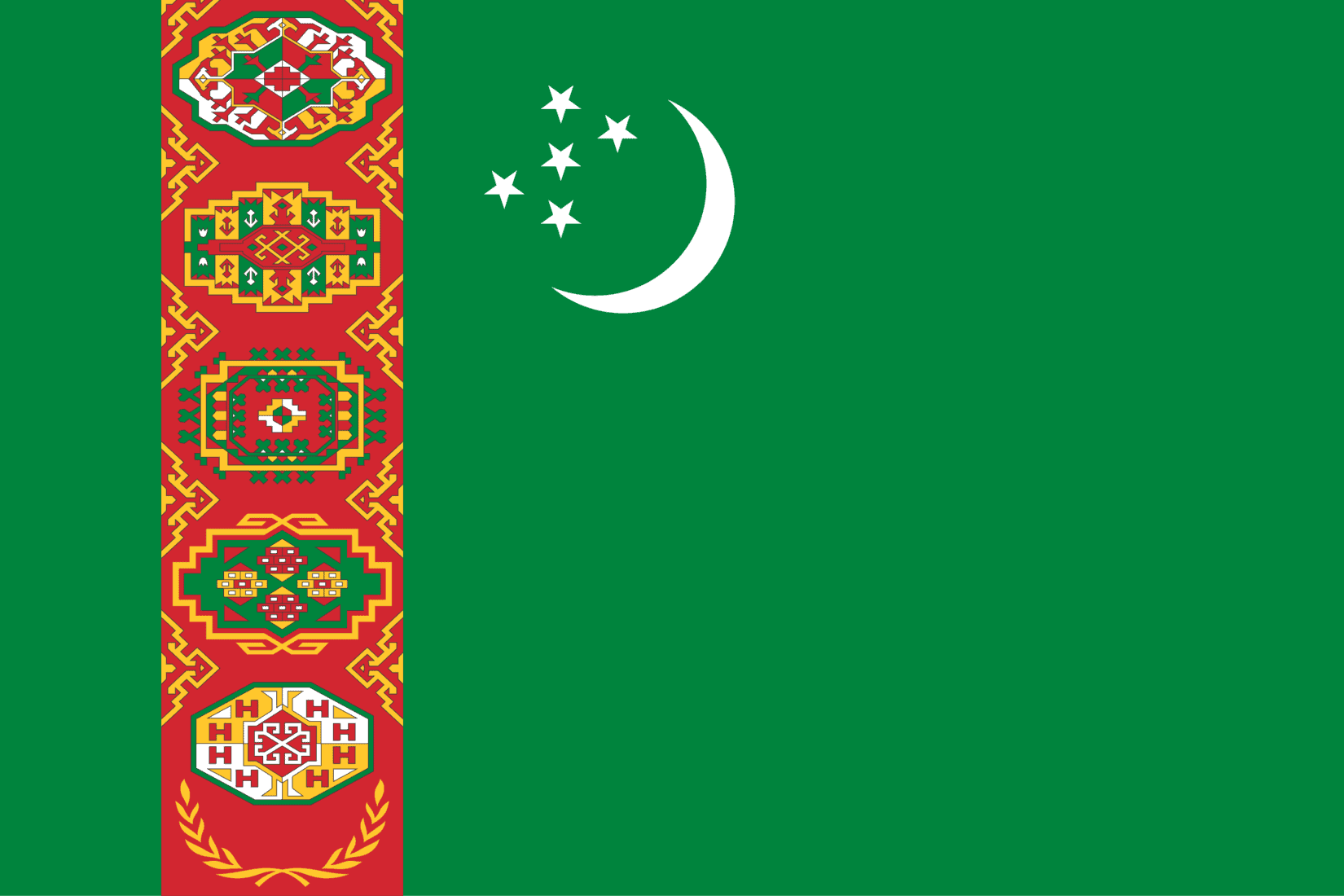

I return home with nearly $500 I never spent, a small Turkmen carpet and the pretty green and red Turkmen flag I see everywhere. I also come home with a profound belief that Turkmenistan, this isolated, paranoid, desert nation, has done something definitely right. I keep thinking the same thing Americans say about Austin, Texas. It applies to Turkmenistan.

“Keep Turkmenistan Weird.”

If you’re thinking of going …

How to go there: Independent travel is not allowed. You must go with a Turkmen-sponsored tour company. I used Saiga Tours, www.saigatours.com. The Australian-based company specializes in Central Asia but also runs tours to the Middle East, Afghanistan, Pakistan and North Korea. They handle everything from the visa to the sightseeing. They are excellent. I paid $1,715 for seven days including airport transfers, accommodations and knowledgeable, frank guides.

How to get there: Flights go to Ashgabat direct from Istanbul, Moscow, Dubai, Frankfurt and Almaty, Kazakhstan, among others in Asia. The four-hour, round-trip flight from Istanbul starts at €580.

Where to eat: Tuncha Cafe, on Oguzhan Kocesi road near Ashgabat’s hippodrome. I paid about $4 for a big plate of plov, Turkmenistan’s signature dish of rice, meat, carrots and onions, a Turkish salad and a soft drink.

When to go: Saiga runs various tours to Turkmenistan all year round. The weather during my last week in September and first week in October was the best I’ve ever experienced overseas: high 70s-low 80s, dry with a cool breeze. I was never hot; I was never cold. It can reach 120 degrees in summer.

For more information: Turkmenistan Ministry of Culture, 993-12-44-2222.

(Part Two: The Gates of Hell.)

October 16, 2025 @ 3:16 pm

Very entertaining blog. Agree with your sentiments around worlds weirdest country! Thanks John.

October 17, 2025 @ 10:54 am

Thanks for the note, Steve. I like it when countries meet my lofty expectations, however weird those expectations are.