Saudi Arabia: The kingdom finally opens its doors to tourists and I stepped through

Crown prince seeks 100 million tourists by 2030

(This is the first of a three-blog series.)

RIYADH — I’m surrounded by 655 glass panels in a giant ball hanging under the pointy tip of one of Saudi Arabia’s growing number of skyscrapers. From the street 267 meters below, the ball looks as if it’s hanging precariously in its own little opening, like a marble swinging from a string. I would compliment the builder for making the Al Faisaliah Centre so secure but I’m not here to pay homage to the Saudi Binladen Group construction company.

I came to see the world’s 12th largest country finally opening itself to the planet after so many years of mystery. From my vantage point at dusk, nothing better symbolizes what I would experience in 12 days in Saudi Arabia. A jagged skyline of skyscrapers cuts through the gray, dusty sky, the buildings beaming like lights on fog-engulfed ships at sea.

Yes, Saudi Arabia is shining a light toward a bright future while trying darken its oppressive past.

Why I came

Coming to Saudi Arabia wasn’t a difficult decision. I ignored my friends’ cliched warnings about public beheadings and women in burqas. Instead, I focused on visiting a country few have seen without a business agenda or a religious quest.

My holy grail as a traveler is visiting places few have been. Saudi Arabia started providing that opportunity Sept. 27 when it offered tourist visas for the first time, outside a brief stretch from 2007-09. To acquire a visa for Saudi Arabia before, you had to be a worker or on the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca, a city still only accessible to Muslims.

But in November, I went online to visa.mofa.gov.sa/visaservices/searchvisa and applied for a 90-day tourist visa in less than an hour for $124. I received it online the next day. I could go anywhere I wanted in the country without any official watching my every move. No one would read my journal. No one would confiscate my photos.

This is not North Korea.

What Saudi Arabia is trying to do

The change in guard is courtesy of Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman, aka MBS, the deputy prime minister. Wanting to make the economy less dependent on the world’s largest oil reserves, which make up 40 percent of Saudi Arabia’s gross domestic product, MBS picked tourism as the diversification vehicle. Among his ideas:

- Vision 2030, a project he hopes to attract 100 million tourists in 10 years and up tourism’s contribution to the GDP from 3 percent to 10 percent.

- Neom, a $500 billion man-made city on marine land near the Egyptian and Jordanian borders.

- Red Sea Project, a lagoon of 50 luxury islands off the Red Sea coast.

All of this has been delayed by the pandemic which has poleaxed Saudi Arabia’s oil industry and dented its bustling economy. Fortunately, I left the country nine days before Saudi Arabia banned flights to and from Italy.

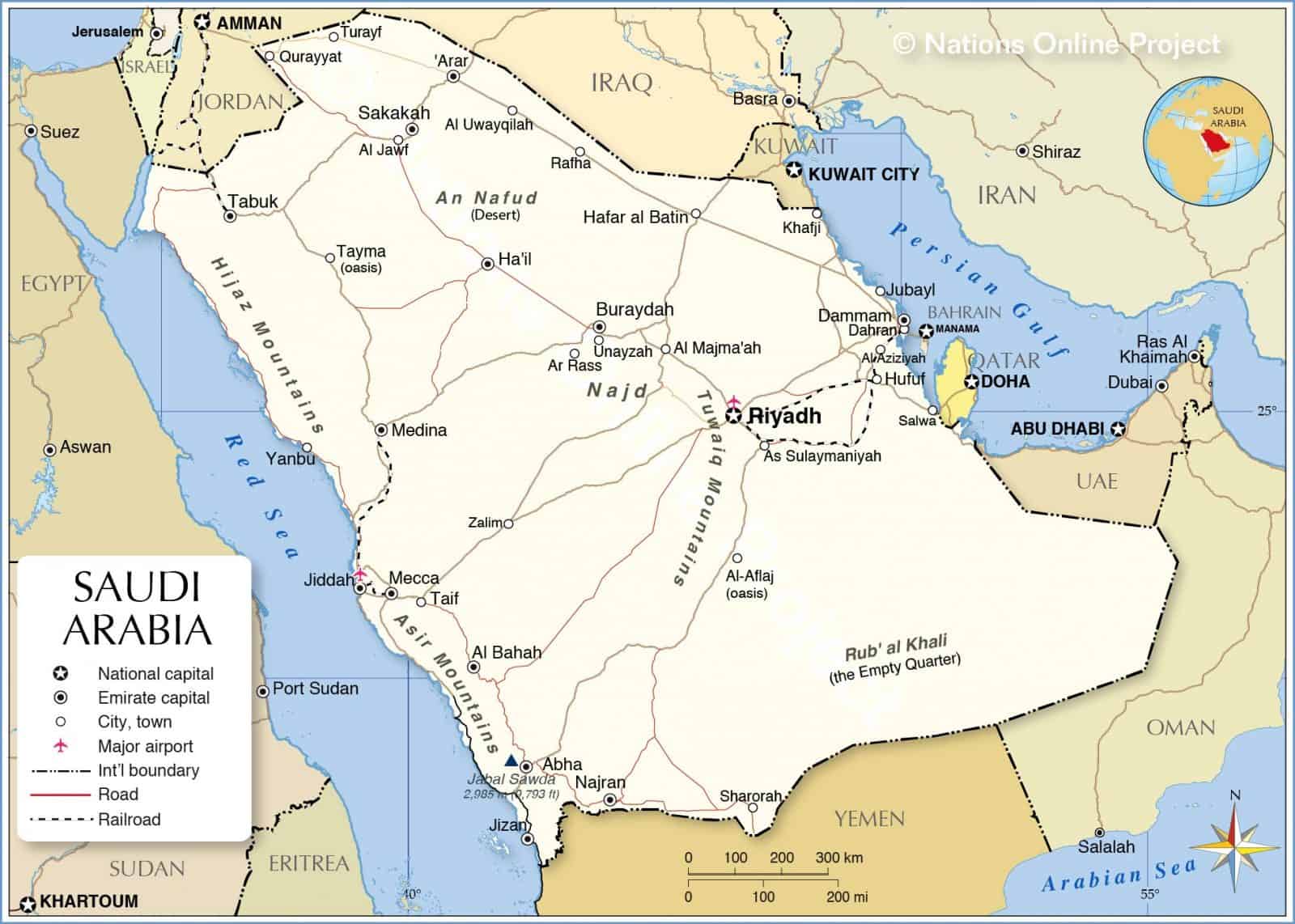

In the meantime, I learn that Saudi Arabia doesn’t need much more else to attract intrepid travelers. Jeddah has one of the most beautiful beach fronts in the Middle East. Madain Saleh is a lightly trodden archaeological paradise, a Petra without tour buses. The Empty Quarter south of Riyadh provides caravans through 650,000 square kilometers of desert and the Eastern Province has an international, liberal lifestyle.

Saudi Arabia’s restaurants are excellent and mostly cheap and the population of 34 million, 60 percent of which is under 20, buzzes with renewed freedom although the concept of free speech remains a total myth.

I also learn that MBS is wildly popular here. MBS, 34, took the nation’s reins from his father, King Salman, in 2017 and started forward-thinking reforms, including the country’s medieval-era women’s rights. He allowed women to drive, attend sports events and travel without a male guardian. He has brought Saudi Arabia into the 21st century on the international entertainment front, attracting a major golf tournament, a cross-country motor rally and live rock concerts such as Black Eyed Peas.

These changes come while getting bashed worldwide for the murder of a Saudi journalist he continues to deny and a list of human rights violations that filled pages in my notebook.

This reputation has kept many travelers from giving Saudi Arabia the time of day. Myself? I gave it 12 days, and offering a tourist visa is the best gift a prince could give the world and his people eager to meet outsiders. I also remember my one travel mantra: The people are not the government.

My arrival

Arriving in Riyadh at night, I am a little more on edge than usual. Despite copious amounts of research, I don’t know if the stories of friendly people with open arms are just propaganda coming from a closed society prying itself open for tourist dollars. But as I wait in line at immigration, with women in burqas so enveloping I can barely see their eyes, I see my first confirmation. A tall, striking airport official with a brilliantly white robe, called a “throbe,” and red checked keffiyeh head scarf, leans over to greet a small boy with his Western parents. The smiling man says in English, “Your first time here? Welcome to Arabia!”

Passing through immigration and customs is no more difficult than Paris or New York. Officials smile. No one asks why I’ve come. I’m out of the airport in 10 minutes.

However, any country tiptoeing into the tourist industry has creases to iron. Saudi Arabia’s big wrinkle is taxi drivers. Nearly all are immigrants, from Bangladesh, Pakistan, Egypt. Outsiders make up 37 percent of Saudi Arabia’s workforce and most have no clue where anything is. They may as well be from Des Moines.

Ten minutes driving down the wide, clean freeway into the city, the Bangladeshi driver, who says he’s lived in Riyadh 28 years, asks me, “Do you know where your hotel is?”

“Huh? No. You don’t?”

He pulls onto a dusty service road and scans the address for five minutes. Silence. We drive another 15 minutes then he hands me his cell phone.

“Put in your address in Google Maps,” he says.

I write down the address but the space isn’t long enough for the listing. He doesn’t seem nearly as upset as I am. We continue driving toward the capital which, despite its wealth, doesn’t have the architectural wonders of UAE: not as many majestic skyscrapers as in Dubai nor the beautifully lit buildings hugging one block like Christmas trees as in Abu Dhabi. Riyadh is a collection of skyscrapers spread out around a pancake-flat city bordering a deep desert the size of Afghanistan. We turn off into a dusty neighborhood of drab apartment buildings, construction projects and Cyclone fences. He stops at another hotel where a man in a throbe swirls his arm around, indicating we must circumvent all the construction.

We circle the block and finally arrive at Al Muhaideb, a modest, nine-story hotel surrounded by sand and, yes, a Cyclone fence. The kind, smiling hotel clerk surprises me with an upgrade to a suite with a living room in soft browns and beiges, two flat-screen TVs and a beautiful view of the city. The skyscrapers seem far away, an indication of why my neighborhood is so dead. My best eating option is a cheap convenience store next door. Guess I’m no longer in Abu Dhabi.

This is my sixth Islamic country in nine months, the 18th of my life. No Muslim country previously was presented in such raw form. I prepare to make the deepest dive of my life into my inner Muslim.

Riyadh sites

The next morning my Bangladeshi taxi driver is puzzled when my highly accommodating hotel clerk asks him to take me to the Masmak Fortress. This is like a New York City cabby not knowing where the Met is. He uses my cell phone’s GPS to wind his way into the center of Riyadh, featuring wide, clean boulevards and big advertising signs. Business offices are understated. Apartment houses are modest. We finally arrive 15 minutes before closing.

The Masmak Fortress is a long, broad sandstone castle anchored by tall turrets on opposite corners. The palm trees out front provide a nice final view for prisoners still beheaded in the adjacent public square. Clue to cab drivers: Masmak Fortress is merely the biggest nationalistic symbol of Saudi Arabia. Built in 1865, the fortress was the sight of a 1902 raid when Ibn Saud, the father of Saudi Arabia, took over the fortress from an army garrison, the first spark in uniting the different kingdoms in Saudi Arabia. The front door I enter is the same door he and his troops stormed through to pound the army. In fact, next to the doorknob remains the spearhead left from the spear Ibn Saud threw at the start of the raid.

The fortress is now a museum displaying everything from single-shot muskets to inkwells, gas lamps and incense holders. All the descriptions are spliced with religion, such as “… with God’s will” and “…with God’s might …” A good film in English talks about the attack and the forming of the kingdom. Saudi Arabia was a lot like Italy. It consisted of little fiefdoms that came together as one nation in 1932, not coincidentally the same year oil was discovered in Saudi Arabia.

Another clueless cab driver gives me an unscheduled tour of all of downtown Riyadh before we finally find the National Museum. It traces the history of Saudi Arabia and Islam from the Ubald Civlization in 5300 BC to the Hajj. It’s a slick, modern two-story palace filled with artifacts from every era and detailed information about Islam and Saudi Arabia and its geology. The first thing I see is a 2.75-ton meteorite found in the Empty Quarter. There’s a huge display entitled “Creation of the Universe” where I walk through rock arches and see an illusion of exploding planets and sounds of the Islamic prayer in the background. It’s quite spiritual and majestic, combining religion with science.

I learn how the Hajj dates back to 2000 B.C. and has been in its present form since 632 A.D. Aerial shots of Mecca show a sea of humanity. Nothing but white throbes crammed into a mosque like toothpicks into a plastic holder. About 2.5 million people pour into Mecca, a city of 1.5 million, for five days, sometimes in the middle of summer. Average July temperature: 111.

Thankful for February’s relatively cool, dry 80 degrees, I know it’s time to see modern Saudi Arabia. I take a cab to the Kingdom Centre, Riyadh’s other trademark skyscraper. It’s a 99-story building with two upright prongs at the top, both connected by a corridor that serves as the observation deck. Entrance is 63 riyals (about 15 euros) and well worth it. Another local and I shoot up the high-speed elevator, my ears slightly popping. We leave the elevator and open the door to the bridge. The view shocks my senses to the core. The bridge curves upward and is surrounded by floor to ceiling windows with the entire expanse of Riyadh stretching to the horizon.

Riyadh is massive. It looks like Los Angeles after a dust storm, which are common here. This is where the veil comes off the riches of Saudi Arabia. I see one wide strip stretching on both sides of the bridge. It’s filled with skyscrapers and high rises of fairly normal architecture. But next to the strip is another just as wide and long where there is nothing, just wide fields of sand. It’s as if they just tore off the top layer to reveal raw earth underneath.

All around it is the real Riyadh: a long, massive swath of yellowish, two- and three-level buildings stretching to the horizon. They are made even more dingy by the sand that apparently fills the air here year round.

The views from these skyscrapers are mind blowing, beautiful and revealing, like I opened the top of a secret box. The National Museum is one of the best I’ve ever visited. Yet the number of other visitors I’ve seen all day could fit in any taxi I’ve taken. An estimated 25,000 tourists applied for Saudi visas the first week they became available. Few are here in February, which would be the height of Saudi Arabia’s tourist season. The prince has much to sell here. But it’s a tough sell.

I’m about to meet one man trying to sell it.

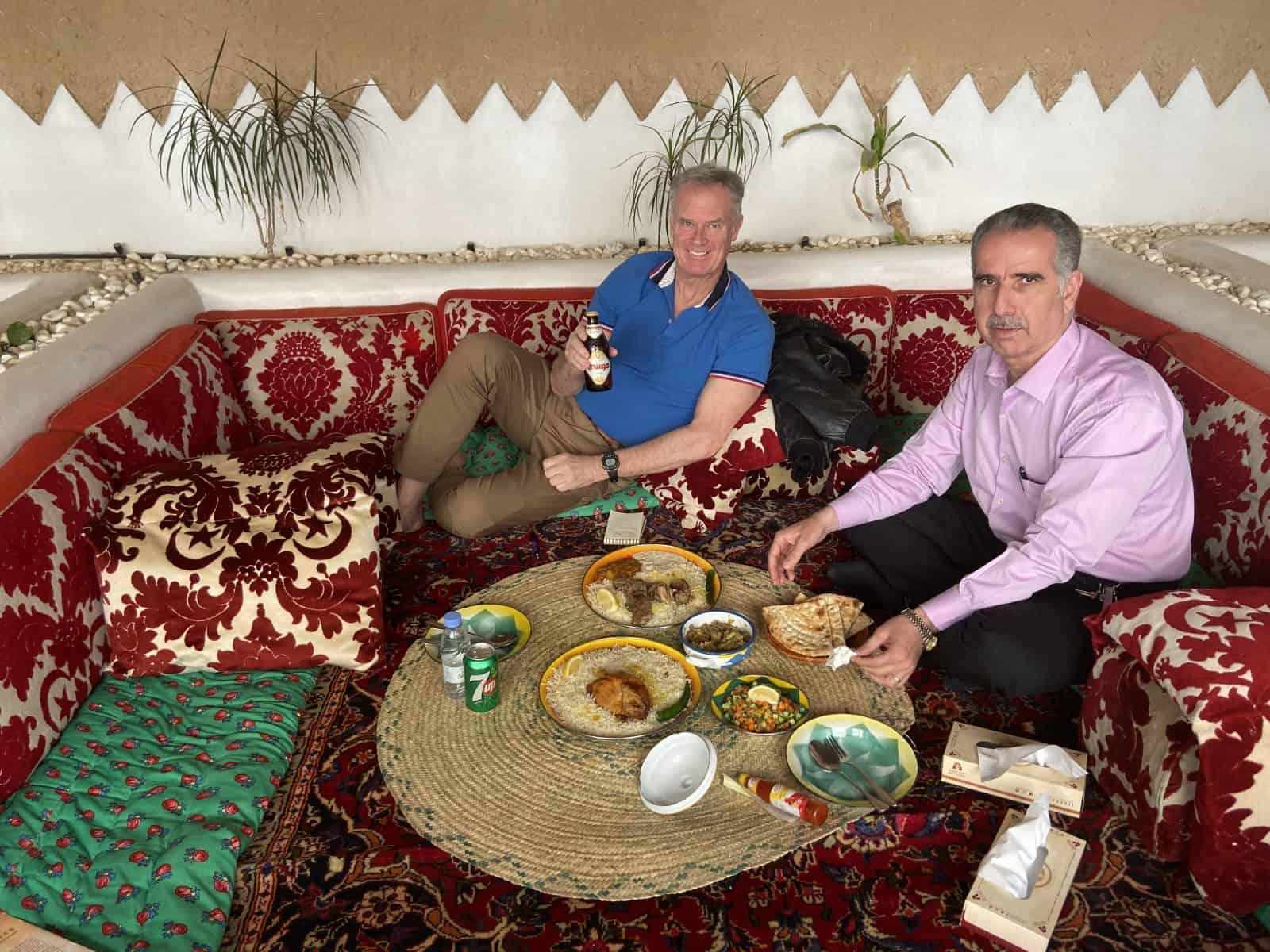

Lunch with a Saudi tourism official

Imad Sulaiman picks me up at my hotel in his Range Rover dressed as a casual businessman in gray slacks and a purple dress shirt. Imad is a major reason I’m here. Owner of Alshitaiwi Travel & Tourism, he manned Saudi Arabia’s small booth at the World Travel Market I attended in London last fall. He and famed Saudi uber blogger, Yousef Al Sudais, enthralled me with stories about the new open Arabia and the easy access. Everything they said has come true.

Born and raised in Damascus, Imad has lived in Riyadh for 31 years. He was around in the boom decade when the economy grew 5 percent every year from 2003-14 and the GDP tripled. At one point it produced 12.3 million barrels of oil a day. Average salary was $51,000. That includes a large working class in the massive construction industry.

Confirming my hotel’s lousy location, Imad said in 30 years in Riyadh he’d never been to my part of town. We drive into the heart of the city, past the big, old airport now used for military and visiting dignitaries.

“Donald Trump came in there,” he says. “When he arrived we had a dust storm.”

Staying neutral, I decline to say, “Bravo for life’s little ironies.”

We go to the place for the most authentic Saudi food in Riyadh. Nadj Village is a chain of five restaurants, one of which I went to my first night in town and had lamb kabash, a traditional saudi dish of lamb, rice and sultans. The layout is eight individual sections covered with thick carpets and pillows. No chairs. No tables. This is dining Arabian style. In the waiting area, I take a seat in a camel’s saddle while our area is prepared. A waiter serves tarragon coffee from about two feet above the tin cup and passes over a small basket of the best dates I’ve ever had: big, fat, juicy and dripping with honey.

Finally seated, I take off my shoes and order Hashi Badya, camel chunks on a rice-covered plate with side dishes on a serving mat the size of a satellite dish. I’ve had camel burgers in Morocco but this is better, like little roast beef balls and just a little gamier. The way they cook it at Nadj Village, I don’t need a fork. The meat falls off the bone.

A glass of white wine or a beer would go great with this lunch. However, alcohol is strictly forbidden in Saudi Arabia and can only be found in compounds of the more savvy — and thirsty — expats. Frankly, I don’t miss alcohol and Imad says other visitors say the same.

Alcohol forgotten

“They’re very happy because this is a new experience,” he says. “It’s a kind of treatment. People enjoy getting away from alcohol. Alcohol is not everything in life.”

Imad says 15,000 visitors poured into the kingdom that first week and the government averaged 45,000-60,000 visa applications in October and November. He had just finished meeting two American groups, one of which is going to the east and another to the north. He’s going to Al-Ula to meet a Japanese group while I’m there. The first line of the new metro system was targeted for the end of the year before the pandemic hit. Eventually, there will be three lines.

The problem with selling Saudi Arabia is public relations that has never been the country’s forte. People only know what they read in the papers. That has been a lot.

“They get the wrong image of the country,” Imad says. “You are here now. How do you feel after two, three days? Everybody has the wrong image of the country but when they come here and discover for themselves, it’s very safe. There are hospitable people. Everybody will love it.

“I’m sorry to say because the media in Western Europe and America are controlled by other parts who don’t like Saudi Arabia or other Arab countries. This is the situation.”

Human rights criticized

Then again, it’s hard to sell a country when it’s known for oppression of women’s rights and public executions. How do you change it? By changing the laws. Women were given the right to drive in 2018, three years after they were allowed to vote, and as of last year tens of thousands had their license. While taking taxis all over town, I often saw women behind the wheel of other cars. I even saw one woman wearing a burqa driving a Range Rover. I wondered how she could see through the niqab headscarf.

“Most of the Saudis teach the women to drive,” Imad says. “They’re training their wives. And not just their wives but their sisters, their daughters to get the license. You visit any school for training the drivers, you see many, many husbands and many brothers that are assisting their sisters and wives to get their license.”

It’s true. In Jeddah a few days later, I meet a group of young Saudis, one of whom is thrilled his wife can drive. “It’s awesome,” he says. “There’s nothing wrong with it. We don’t have to drive them everywhere. We’ve been waiting for this.”

I then tiptoe into a sensitive topic. Imad knows it’s coming. Human rights. I’ve heard about Chop Chop Night, the public executions. To clarify, it’s not at night. They’re during the day and are not regularly scheduled or announced. To see one, you must be around the Masmak Fortress when they bring out a prisoner. According to Amnesty International, an estimated 2,000 people were executed in Saudi Arabia from 1985-2013. Yes, they do beheadings for serious crimes such as murder but they do not cut off hands of thieves.

“Who told you that?” he asks me. “That’s what I’m saying. This is one of the sides of the bad image. You guys got the wrong image. Who’d cut off your hand for stealing a piece of bread? They do it for major things. Someone takes a piece of bread or whatever it means he needs it. He’s not a thief. But if someone goes and kills someone in his home and takes his vault or money, this is really, a serious, serious crime.”

How serious crimes are other religions and homosexuality? They’re still illegal. Homosexuals are mentioned in reports of executed prisoners, many of which are often members of the Shiite minority. Top women’s rights activists remain behind bars and are awaiting trial. In 2014, the BBC reported that a blogger named Raif Badawi, who started a website called Liberal Saudi Network, was sentenced to seven years and three months in prison, 600 lashes and fined 1 million riyals ($266,000) for “insulting Islam.” CNN reported that Dr. Walid Fitaihi, a dual U.S.-Saudi citizen, was beaten, tortured and jailed for more than two years for motivational speeches aimed at pushing Saudi Arabia to more “American-oriented ideas” of civil rights and equality. Saudi officials deny any mistreatment of citizens.

Freedom House’s annual survey of political and civil rights called Saudi Arabia among the “worst of the worst.”

Media welcome

Imad doesn’t bristle but says “don’t trust” Amnesty International and that freedoms are changing. The kingdom is inviting more media. He says the local press does criticize the government and people are speaking out more without repercussion. I don’t see it. In 12 days in Saudi Arabia, I never hear anyone criticize the prince. Then again, maybe he’s as popular as Imad says: “All the changes come with him. Other neighboring countries, they wish they had the same crown prince as Saudi Arabia.”

He drives me back to my hotel and gives me tips about seeing Diraiyah, the Riyadh suburb and World Heritage Site that is the Saud ancestral home. He tells me some fine points about renting a car in Al-Ula.

He looks at his watch. He’s working until 10-11 p.m. every night accommodating the travelers to see for themselves what they’ve read about for so many years. He’s taking it partly upon himself to help his adopted country. He tells me a story about a man who recently visited.

“(He) said, ‘Imad, this is unbelievable,’” he says. “His wife said, ‘No, I won’t go.’ He came back with photos and she said, ‘I will come next month.’ She was afraid. He saw for himself it’s very safe. This is our job now to try as much as we can to change the image about our country.

“And we’re doing very, very well.”

We’ll see how it emerges from the pandemic. In April oil fell 300 percent in daily trading. The country has a $41 billion deficit, according to ISPI, the international political website. That’s not good when officials say another 500,000 hotel rooms will be needed to accommodate the vision of 100 million tourists. Michael Stephen, Middle Eastern analyst at the Royal United Services Institute in London, told The New York Times this month, “I think Vision 2030 is more or less over.” Karen Young, the Gulf analyst for the American Enterprise Institute, said that at recent oil prices, Saudi Arabia will be broke in three to five years.

Maybe the crown prince is right. Maybe it’s time tourism came to the rescue.

Next: Jeddah — Enduring gem on the Red Sea.

May 29, 2020 @ 9:46 am

Interesting piece, but it seems like it should be harder to get past “the murder of a Saudi journalist he continues to deny and a list of human rights violations that filled pages in my notebook.”